Michael McCormick, Francis Goelet Professor of Medieval History, describes new research that shows an early plague pandemic reached post-Roman Britain.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Plague genomes show extent, diversity of massive Roman-era pandemic

Interdisciplinary collaboration between Max Planck, Harvard researchers bears fruit

New research on one of history’s most devastating plagues shows that it spread farther than previously believed, reaching post–Roman Britain, and provides new information about the plague bacteria’s evolution during a pandemic that lasted more than 200 years.

The work, conducted by an interdisciplinary team from Harvard University and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany, covered 21 archaeological sites across Europe and the Mediterranean that date to the time of the Justinianic Plague, which first struck in 541 A.D. and returned in multiple waves until 750.

Samples taken from human remains at the sites were examined for the DNA of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium known to cause the plague, which centuries later swept across Europe in perhaps history’s most famous pandemic, the Black Death, which may have killed as many as half of all Europeans.

Though less widely known, the Justinianic plague is believed to have been nearly as deadly. It began during the reign of Emperor Justinian, who ruled the Roman Empire’s eastern portion from his capital in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), after the fall of Rome and the western portion of the empire. The pandemic centered on Constantinople and ports around the Mediterranean. Though reports from the time say the first plague outbreak killed half the population, scholars of the era disagree on its impact. Some argue that, though deadly, it played little role in shaping the society and the economy. Others argue that it had the potential for history-altering impacts on a wide array of human activities.

Such impacts, however, remain unproven and are the subject of active investigation by the research team, which includes historians, archaeologists, and experts in ancient DNA under the auspices of the 20-month-old Max Planck-Harvard Research Center for the Archaeoscience of the Ancient Mediterranean (MHAAM).

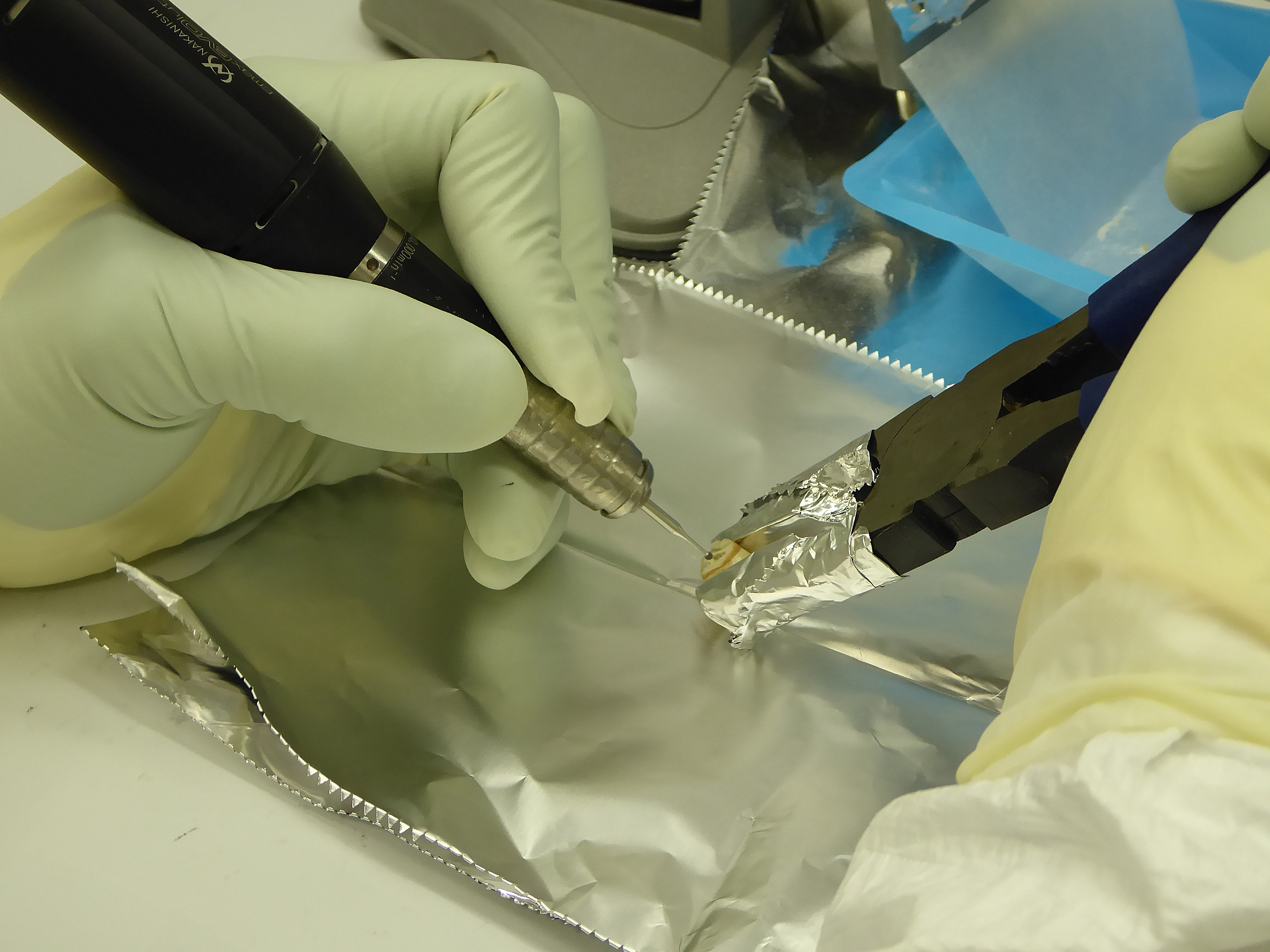

A researcher works with a sampling of a tooth from a suspected plague burial and the remains of a plague victim thrown into a demolition trench of a Gallo-Roman house in southern France toward the end of the sixth century.

© Evelyn Guevara; CNRS – Claude Raynaud

In the work, published recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers reconstructed eight new Y. pestis genomes from the samples gathered from sites in modern-day France, Germany, Spain, and Great Britain. The genomes provided further confirmation that it was indeed the plague — known in its various forms as bubonic, septicemic, or pneumonic — that swept the Mediterranean during Justinian’s time. Though the cause of the pandemic had long been debated, plague was confirmed as the likely causative factor in 2013 and again in 2016 when researchers announced they’d identified Y. pestis genomes in graves in Bavaria dated to that period.

Two of the sites in the current study are on the Mediterranean coast — one in France and one in Spain — providing important confirmation of plague bacterium in the coastal region where it is believed to have had its biggest impact, according to Michael McCormick, Francis Goelet Professor of Medieval History, steering committee chair of the Harvard Initiative for the Science of the Human Past, and co-director of MHAAM. Those samples were taken from sites identified as promising by Harvard students in McCormick’s graduate seminar.

Historians got the work going, scouring written records of the time for mass graves in heavily populated areas, and multiple or apparently hurried burials in smaller villages. In one case, for example, six bodies were laid in a long trench left by the prior theft of foundation stones, an interment, McCormick said, that smacked of an emergency burial in a convenient hole. Three of the six skeletons found on the French coast northwest of Marseilles still held Y. pestis DNA.

The genetic analysis was conducted by scientists at the Max Planck Institute, including lead authors Marcel Keller and Maria Spyrou, and showed that there was genetic diversity among different plague strains during the pandemic’s two centuries. It also highlighted the bacterium’s evolution over time, as samples taken later in the pandemic showed a deletion of genes related to two virulence factors.

“This study shows the potential of paleogenomic research for understanding historical and modern pandemics by comparing genomes across millennia,” Johannes Krause, director of the Max Planck Institute and co-director of the Max Planck-Harvard Research Center for the Archaeoscience of the Ancient Mediterranean, said in a statement.

Researchers from various disciplines gathered early on to collaboratively identify key questions and brainstorm potential paths of investigation. Then, once historians identified likely sites where plague victims might be buried, archaeologists visited to uncover samples that were then turned over to ancient DNA experts for DNA extraction, reconstruction, and analysis. In the process, McCormick said, graduate students and undergraduates from Harvard and Germany who worked on the project learned to cross disciplinary boundaries and “speak the languages of history, archaeology, and genetics to each other, as naturally as earlier generations of scholars learned Latin and Greek.”

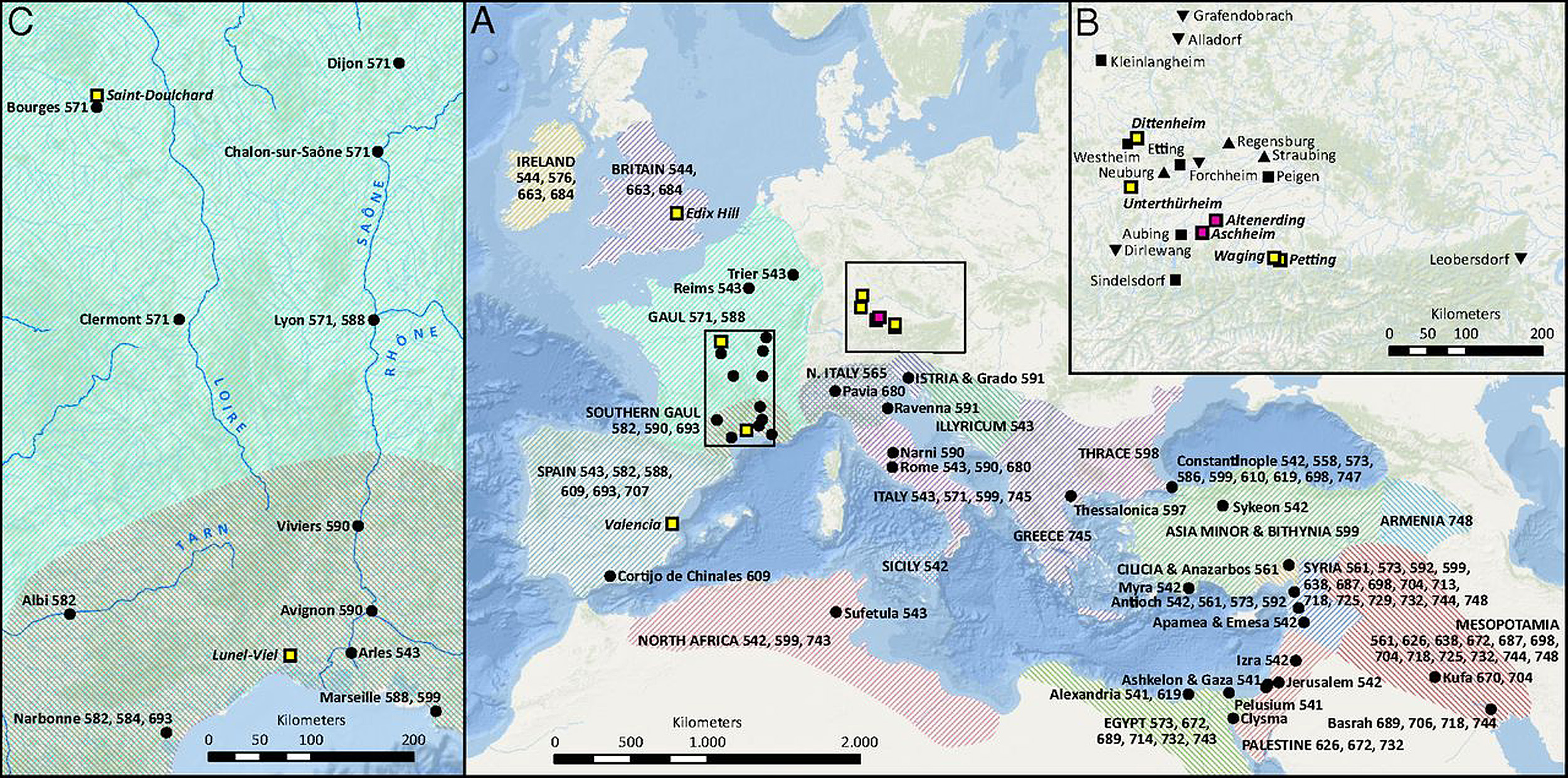

The geographic extent of the first pandemic and sampled sites. (A) Map of historically documented occurrences of plague (regions shaded, cities depicted by circles) between 541 and 750 in Europe and the Mediterranean basin. Sites with genomic evidence for Y. pestis are shown as pink and yellow squares. (B) A closeup of A showing all sites in Germany and Austria that were included in this study. Sites tested negative are marked with black squares and triangles. (C) An enlarged inset of A shows reported occurrences in France.

Source: “Ancient Yersinia pestis genomes from across Western Europe reveal early diversification during the First Pandemic (541–750)”

“It’s really about working together right from the beginning as a team,” McCormick said. “It’s a fantastic example of how we can get new results that are really important in a debate that, kind of paradoxically, is heating up right now about whether the Justinianic pandemic was an important thing or not, just as new evidence really starts to appear. The archaeological and archaeogenetic evidence is opening up a whole new — not just a chapter — a whole new book on this great story.”

The findings of the plague in Britain, for example, McCormick said, are significant not only because the disease hadn’t been confirmed there previously, but also because the plague DNA found there appears to be more basal in its genetic lineage. That indicates there was likely a connection — perhaps through commerce — to places within the Roman Empire where the disease was first reported, such as Egypt.

“If that’s so,” McCormick said, “that suggests almost direct transmission from Egypt to Britain.”

Where the British burial was found provides another opportunity to learn about the times, McCormick said. Given the pandemic’s Mediterranean epicenter, one might have expected to find plague in western Britain among the Romano-Celts who carried on in the wake of Rome’s withdrawal more than a century earlier. Instead it was found in an Anglo-Saxon cemetery, among people who were expanding their control of Britain at the time. The find raises the question of how the plague came to the four individuals in whom it was detected, McCormick said, and the answer will further illuminate the networks between people — even enemies — that existed at the time.

“We don’t know, but now we’ve got to find out,” McCormick said.

McCormick said researchers will continue to expand the picture of this period, focusing on the role the plague played not just in human health, but, given its extraordinary death rate, also in warfare, politics, economics, and a whole host of other human activities. As the story of more deaths gains detail, it will be possible to classify the dead into a “family tree of contagion,” organized by time, space, and the genomic characteristics of the plague that killed them as it burned across the landscape.

“We now have a pathogen whose molecular history we can follow for thousands of years,” McCormick said, adding that our understanding of the plague’s impact on this era will continue to grow. “The jury’s out, evidence is accumulating, and we’re all going to learn as we go forward.”