Beware the deeper water

iStock

Researcher documents summer surge of great white sharks off Cape Cod

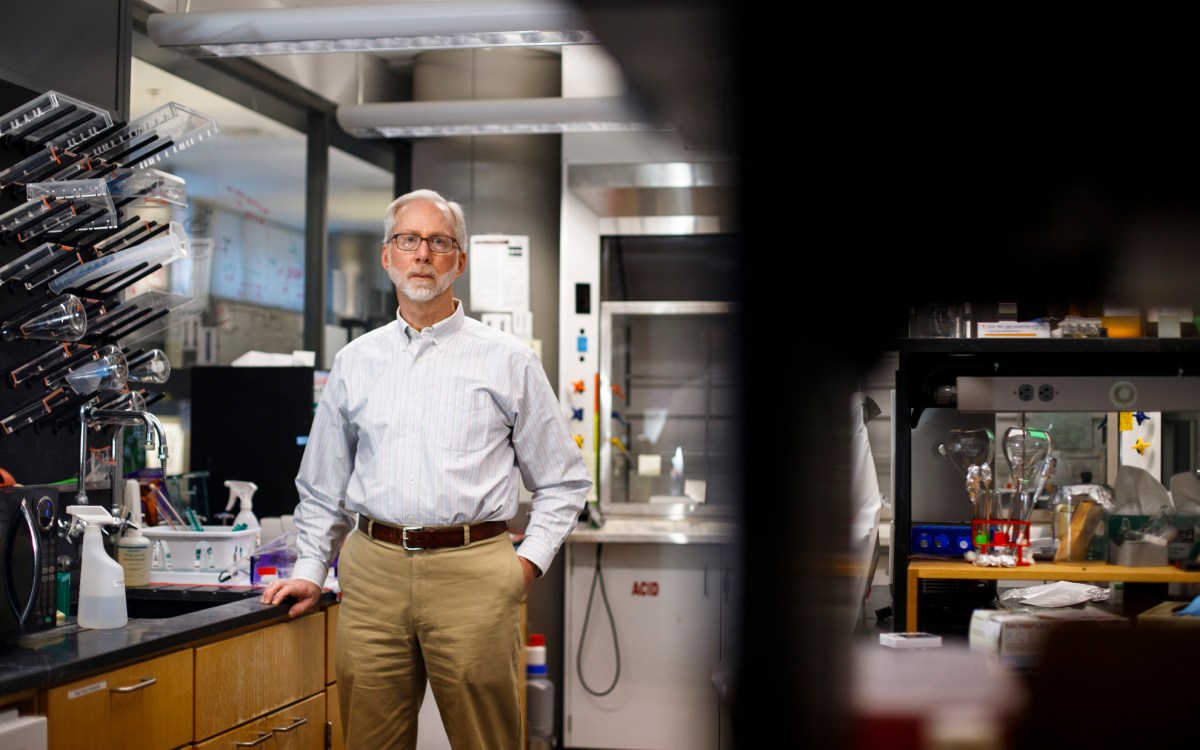

They increasingly hunt in the waters off Cape Cod, and sometimes humans get in their way. Last summer, scientist Greg Skomal was one of them.

The shark expert has been studying the massive marine predators for years, but even as a seasoned observer he got a fright when a great white shark breached, jaws open and only inches from his feet, as he stood on the pulpit of a small boat off Cape Cod, where he was looking to tag some of the giant visitors.

The shark could have been spooked by the boat, Skomal told a Harvard crowd Tuesday evening during a talk sponsored by the Harvard Museums of Science & Culture that focused on the increasing great white population off the Cape’s summer shores. Or the shark could have been in search of his next meal.

“I know what it’s like now to be a seal,” said the biologist and senior scientist at the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries.

For the past decade, Skomal and a team of researchers have been tagging and studying great whites off the Massachusetts coast. He hopes his work tracking their movements, biology, and behavior will help shed light on the animals, support protection efforts for them, and perhaps help reduce their encounters with humans. The gray seal population along the Cape’s shores has jumped dramatically in the past 20 years, a result of the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. The sharks, who hunt the seals, have also increased in number in large part due to protections put in place in 1997.

“We are seeing this general overall population rebound … after being hit pretty hard by the development of commercial fisheries in the ’80s and ’90s, but also by some recreational fisheries that targeted white sharks after [the movie] ‘Jaws’ came out,” said Skomal. “And white sharks were also not only rebounding but redistributing themselves to near coastal areas, and we felt that that was very highly correlated with the fact that seals were coming back.”

For the past decade, scientist Greg Skomal has been tagging and studying great white sharks off the Massachusetts coast.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

As the gray seals have increased — Skomal estimates roughly 30,000 now make the Cape their year-round home — so too have their No. 1 predator.

“When you show me big numbers of seals,” said Skomal, “obviously you are going to have something that wants to eat them.” And with the overlap of seals, white sharks, and people in the water in summer, he said, “the probability of negative interactions goes up.”

Great whites are important in maintaining the marine ecosystem’s delicate balance. The pristine Cape beaches on which the seals love to bask have become prime feeding grounds for the sharks, which attack in their shallow waters. While shark attacks on humans remain rare (according to some estimates, the odds of being attacked by a shark are one in 11.5 million), last summer sharks attacked two people on the Cape. A man from New York who was out for a swim was bitten about 10 feet off Longnook Beach in Truro in August and survived puncture wounds to his upper leg. Just over a month later, a man from Revere on a boogie board was attacked off of Newcomb Hollow Beach in Wellfleet. He died following the attack.

Though that was the first shark fatality in the area since 1936, the attacks and the rising numbers of sharks sparked safety concerns for swimmers.

“We are seeing an increase in these kinds of interactions. And as you can imagine, for those of us who love to go to Cape Cod, there’s some concern out there,” said Skomal, who meets regularly with beach managers and town officials about what to do.

For Skomal, there is “no silver bullet … there’s nothing we can implement right now.” Changing the seals’ or sharks’ behavior is likely impossible, he said. One option involves changing human behavior, something Skomal thinks can be informed by his research.

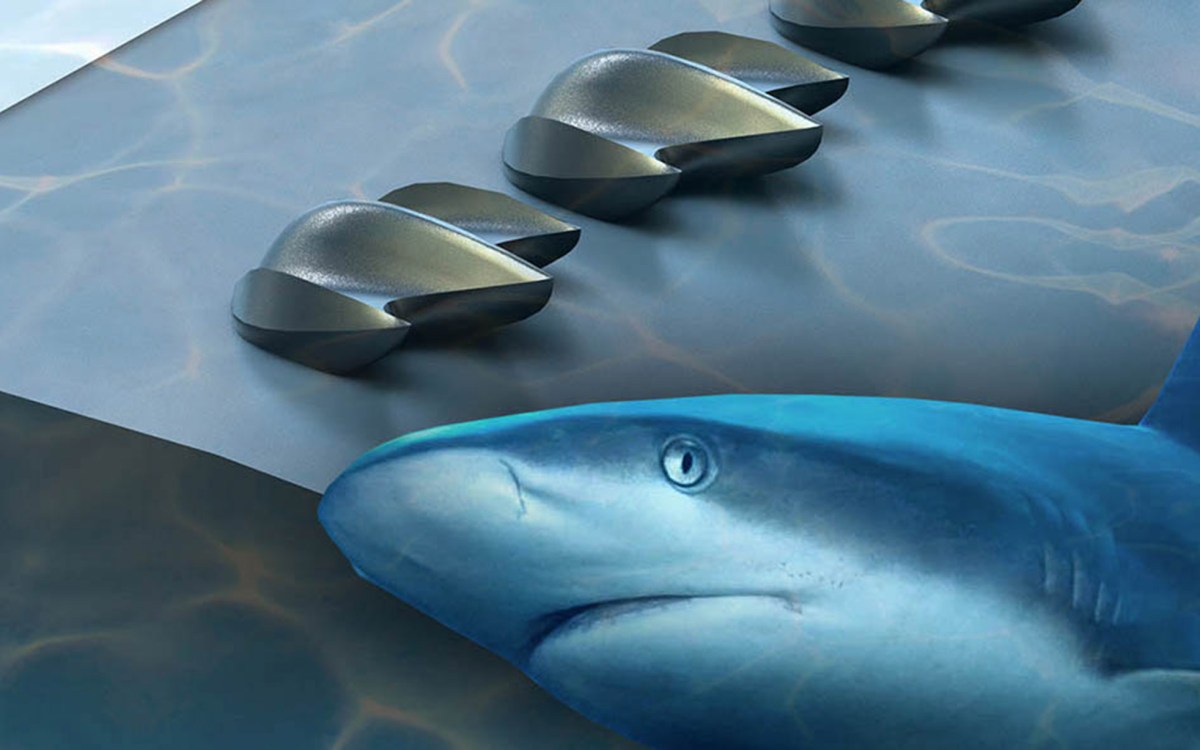

Using a series of trackers attached to some sharks’ fins, Skomal and other researchers monitor the sharks’ movements and record information such as the depth, water temperature, light levels, and ambient conditions where they swim, as well as their direction and their speed.

To date, Skomal and his colleagues have tagged 151 white sharks. The information provided from those animals indicates that “white sharks are everywhere” off the Cape’s outer beaches, and less likely to be in Cape Cod Bay, a finding that correlates to the presence of their prey. “Show me big piles of seals,” said Skomal, “and I am going to show you white sharks wanting to eat them.”

The data reveals the sharks travel thousands of miles to warmer waters during the New England winter and spring, and typically begin returning to Massachusetts waters in June. A few are detected in the early summer, said Skomal, and their numbers peak in August, September, and October. As the water temperature drops, the “number of detections goes down and the sharks leave.” When they are here, they spend about 50 percent of their time in shallow water.

“If we can have some kind of forecast as to when these sharks are likely to be in certain areas, then I think that that at least gives some beach managers information that they can work with. I am not sure we will ever get there.

“What we are still lacking are those direct observations,” he added, “particularly at times when we are not out there.”

“Show me big piles of seals, and I am going to show you white sharks wanting to eat them.”

Greg Skomal

While some species of sharks keep dawn and dusk feeding times, it has never been proven for those off the Cape, said Skomal. By attaching camera systems to the sharks, Skomal and his colleagues hope to obtain more of that data this season and assess “when, where, and how these sharks are feeding.”

For now, Skomal said Cape swimmers this summer should avoid swimming near seals, keep close to shore, and never depend on being able to spot a shark.

“Don’t rely on seeing the dorsal fin in shallow waters,” he said. “I’ve probably seen that 10 times in 10 years. The classic Steven Spielberg shot of the white shark doesn’t really happen.”

While Skomal doesn’t know exact numbers of great whites off the Cape, a colleague is examining data from the past five years to determine a figure.

“I can tell you, from our raw data, [there are] at least 320 individuals that we have identified over the course of the last five years, but [there are] likely many more than that.”