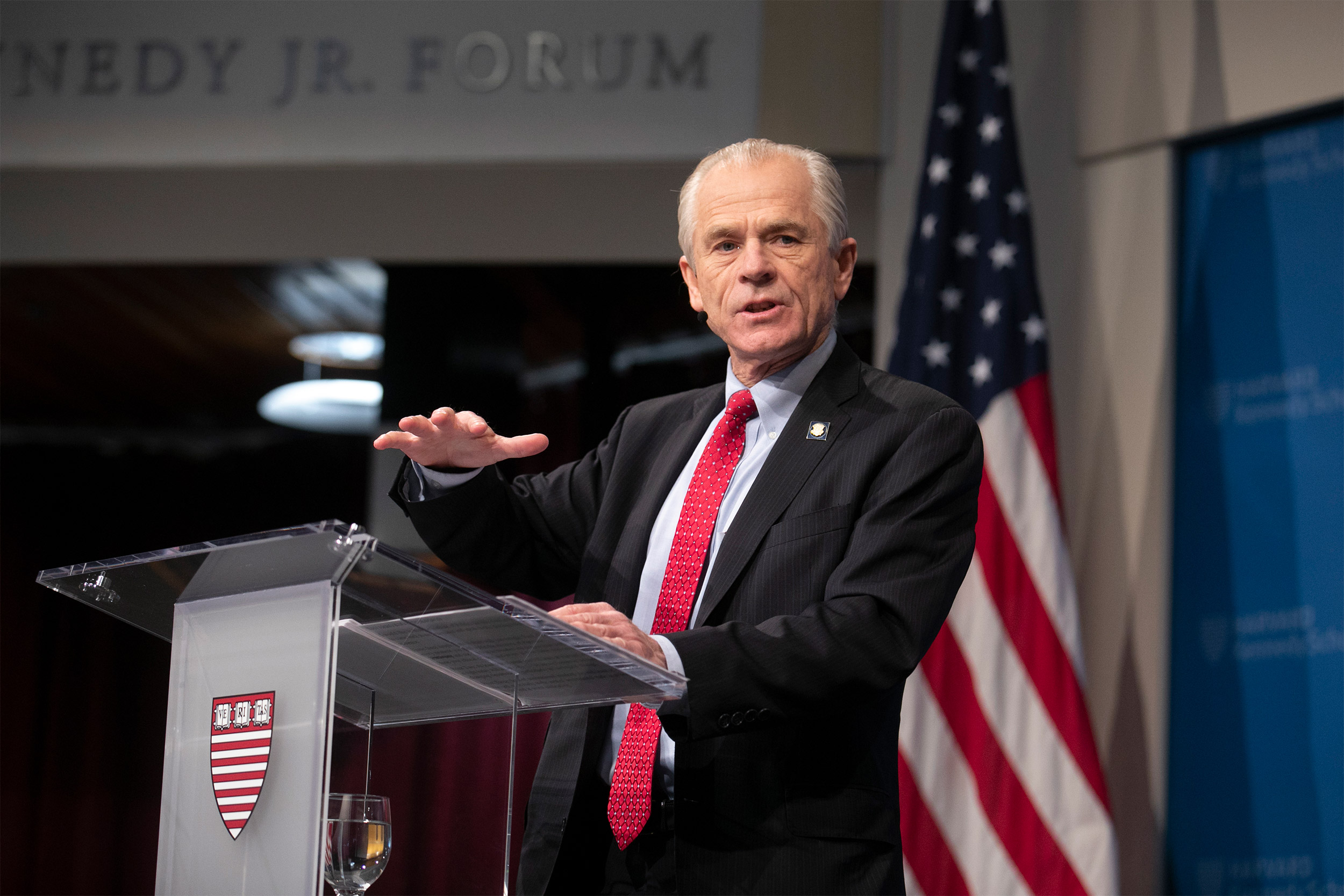

Peter Navarro, director of the White House Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy, gives a presentation on U.S. trade policy.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

A ringing defense of Trump on trade

Economist Peter Navarro says policy shifts are bearing fruit

President Trump’s trade czar, Peter Navarro, said Thursday night during a speech at the Institute of Politics’ JFK Jr. Forum that the administration’s efforts to remake American trade policies, pressure China to reform its practices, and revamp the tariff system are boosting the American economy.

Navarro ’77, Ph.D. ’86, has been informing Trump’s ideas on trade since the 2016 presidential campaign, ever since Jared Kushner shared one of Navarro’s books, “Death by China,” with his father-in-law, who had been espousing similarly critical views of trade with that nation since the 1980s.

Now assistant to the president and director of the Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy, Navarro, besides being a prolific author, is a former Democrat who has run for office several times, and is a professor emeritus of economics and public policy at the University of California, Irvine.

Trump has begun enacting several of Navarro’s policy proposals, and Navarro said they’re having the desired effects.

“Stripped of rhetoric,” Navarro said during his Kennedy School appearance, “the president’s tariffs on steel and aluminum represent one of the most successful applications of a defensive trade polity in U.S. history. … Billions of dollars of new investment have poured into these industries. Capacity utilization and employment are up. And after a brief spike, prices are coming down just as theory would predict. Meanwhile, the downstream industries that were supposed to be hurt are creating all sort of new jobs.” Reviews of the tariffs in the press have been considerably more mixed.

Navarro’s central thesis, “Ricardo is dead,” refers to the early 1800s British political economist David Ricardo, who argued that international free trade was always beneficial, and whose theories still hold sway.

But, said Navarro, those theories don’t work well in the real world today and “no longer [have] any relevance in global markets dominated by industrial espionage, rampant cheating, intellectual property theft, forced technology transfer, state capitalism, and currency misalignments.”

The U.S. GDP increased last year, jobs have been added for African Americans, Hispanics, and women, and some wage gains have been made. Navarro ascribed those results to “the most active and successful trade agenda of any modern president.”

He cited other Trump administration policies that have proven successful, particularly in military-allied industries, including production of an F-16 jet fighter that he said resulted in Lockheed Martin creating 400 direct jobs in Greenville, S.C., and up to 18,000 more outside it, as well as a recent executive order that will help Navy veterans join the merchant marine, “which is critical to U.S. military logistics.”

“Ricardo is indeed dead. Under President Trump, long live free, fair, and balanced trade.”

Peter Navarro

Navarro criticized the “flood of counterfeit goods and contraband such as fentanyl into this country,” mostly from China, and said that when people buy from third-party online sources they have about a 40 percent chance of getting fakes. “Our policy goal is to turn this flood of contraband and counterfeits to a trickle,” he said. “This will not only protect consumers and save American lives, but it will also create American jobs.”

Navarro praised Trump and said, “There are far too many D.C. bureaucrats in what some have called the Deep State who never got elected but who somehow think that they know better than the elected officials they serve. Please hear this: There’s no ethical high ground to be found in such disloyalty, only a road to ruinous harm to our democracy.”

He recalled the “figurative and quite literal dark days” of the 1970s oil crisis, pointing out that, because of modern fracking techniques, the U.S. has gone from net oil imports of 10 million barrels a day in 2005 to about 4 million now.

Saying that Ricardian economics were not based on “the possibility that one or both trading partners will lie, spy, cheat, or steal,” he provided five examples of China allegedly doing those things, from hacking computers to learn trade secrets, to putting American companies out of business by grabbing market share with cheap goods, to manipulating its currency.

“If Ricardo were alive today,” Navarro asked, “what would he say about this deviant economic model? … I daresay none of you have been asked that in any of your economics classes, but maybe it’s time that those questions be asked.”

He then parsed the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) nonreciprocal trading system’s most-favored-nations (MFN) rule, which essentially requires that countries not discriminate among their trading partners. That is, they must apply the same tariffs on any given goods across the board, with some exceptions.

“The catch,” Navarro said, is that “nothing in the MFN rule requires a WTO member to provide equal — that is reciprocal or mirror — tariff rates to its trading partners. Rather, WTO members are free under the most-favored-nation rule to charge systematically higher tariffs to other countries, so long as they do that to everybody else.”

The MFN tariff applied to autos in the U.S., for example, is 2.5 percent. Canada’s is 10 percent, China’s 15 percent, and “India’s in the stratosphere at 125 percent,” he said. “Does anybody here think that’s fair? Any takers?”

The countries that get hurt most under such a system, he said, are those that have the lowest tariffs on average — like the U.S.

Peter Navarro explains his views on America’s future in trade.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

“America, the piggy bank, will continue to be plundered by a trade deficit that transfers more than half a trillion dollars of American wealth a year into foreign hands. These observations led me to yet another piece of conventional, fossilized wisdom propagated right here in academia — namely that trade deficits don’t matter.”

In support of his argument, he quoted legendary investor Warren Buffet as saying, “Our country has been behaving like an extraordinarily rich farmer who possesses an immense farm. In order to consume 4 percent more than we produce’ — that’s the trade deficit — ‘we have day by day been both selling pieces of the farm and increasing the mortgage on what we still own.” Buffett has called this being “colonized by purchase.”

Navarro admitted that the linkages he made between unfair trade practices and the trade deficit are “not accepted by the economics profession, just not accepted. It’s intuitive, but they’re just not buying it.” He argued, though, that “in such an environment of unfair trade, it’s perfectly rational for Americans to consume more and save less, with the result being a traditional deficit that’s higher that it would otherwise be.”

Many of Navarro’s assertions are considered well outside the mainstream of economic thought.

Largely because of them, Trump has received two letters from economists in recent years, one in 2016 signed by 370 economists that decried his policies, and the other last May signed by more than 1,100 economists voicing their opposition to tariffs and protectionism. Navarro was respectfully heard during his Harvard appearance.

In closing, he said, “It’s long past time for the ivory tower to reimagine and reengineer its models of trade so that they conform far better to the realities of the international trading arena and the very real plight of the people who live not in Cambridge or Manhattan or Bonn or Brussels, but rather in the factory towns of America and across the ranches and farms in this great country.

“And for those of my Ricardian colleagues who continue to resist such long-overdue change, I will simply remind you of what Professor Paul Samuelson once said about the difficult and painful transition from classical economics to Keynesianism in the 1930s. Quipped Samuelson, ‘Science advances funeral by funeral.’ I just hope I’m still around to see my own economics profession advance beyond the bankrupt Ricardian model.

“Ricardo is indeed dead. Under President Trump, long live free, fair, and balanced trade.”