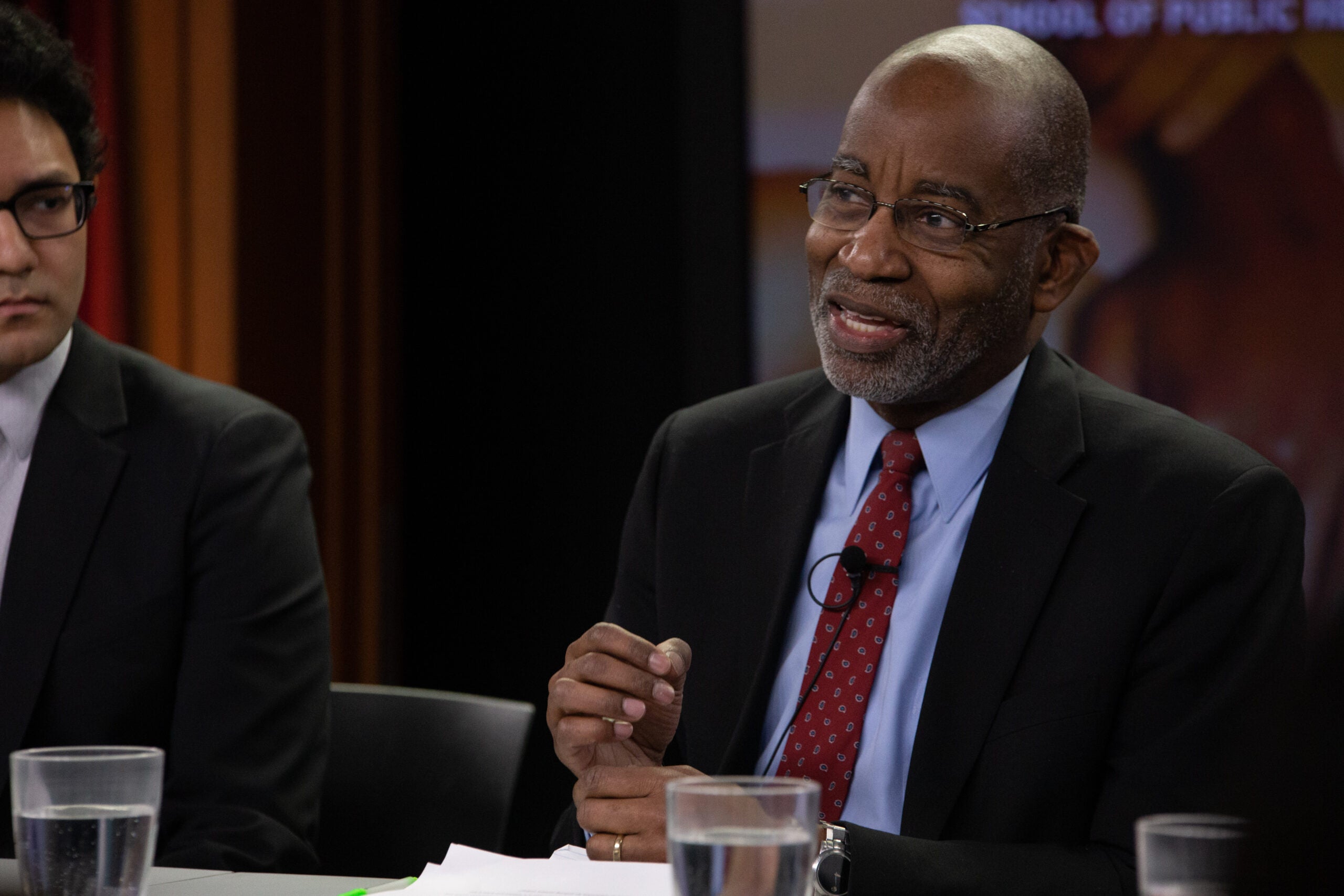

Maureen Costello (from left), Dipayan Ghosh, David Williams, Oren Segal, and Phillip Martin participate in Wednesday’s Chan School forum, “The Spread of Hate and Racism: Confronting a Growing Public Health Crisis.”

Sarah Sholes/Harvard Chan School

The endless struggle over racism

Forum examines rising tide of hate, while promoting approaches that encourage tolerance

Picture a world where political leaders refuse to promote racist stereotypes, where social media companies break down hate-filled echo chambers, where police are trained to counteract implicit bias, and where schools teach children tolerance so all feel safe.

That’s the complicated recipe to fight ongoing and rising racism and hatred in the U.S., experts at a Harvard forum said Wednesday. The complex response is needed because the problem is driven by a confluence of factors and amplified by the ways that technology has developed in recent decades.

“I had a friend, a European, say to me, ‘Whatever happened to your country?’ and he went off on how bad everything was. And I said, ‘Remember, this is a country that just a few years ago you were cheering because of the election of Barack Obama as president,’” said former Wisconsin Gov. Jim Doyle. “And it’s not like everybody suddenly moved out of this country and a whole new group of people moved in. What happened is we are a complicated country, and, while we’ve talked about the problems [with racism] here, we are a country of great tolerance and of acceptance.”

Doyle joined other panelists remotely for “The Spread of Hate and Racism: Confronting a Growing Public Health Crisis,” a session of The Forum at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Doyle pointed at education — both formal and informal — as key in the fight against racism and hatred. He also cited the power of the ballot box to change leaders who foster division. Some intolerant views stem from ignorance and lack of exposure to people of different backgrounds, he said, while others are reinforced by a national political debate that often supports negative racial and ethnic stereotypes.

Statistics say incidents of hate crimes were up in 2017 for the third consecutive year, punctuated by headlining episodes like the murders of 11 people in a Pittsburgh synagogue and the two African-Americans in a Kentucky grocery store, both in October.

“Acts of hate and racism, whether online or in person, are painfully visible these days,” said Phillip Martin, senior investigative reporter at WGBH, a contributing reporter to PRI’s “The World,” and moderator of the event.

Though the national political debate has played a part in fostering an environment permissive to intolerance, panelists said, there are other factors at work as well. Dipayan Ghosh, Pozen Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, pointed to the “commercial regime” that underlies the internet and an array of its services and platforms. That regime, he said, uses technology to create services that are compelling, even addictive, and designed not for the public good but to keep users on the sites and engaged in their services. These companies not only design “precise and sophisticated algorithms” to capture people’s attention, they use data from browsing habits, social content, and past purchases to target them as individuals, curating content in their social media feeds and customizing advertising to them.

That model has created a reinforcing environment for views of every kind, Ghosh said, yet companies have not been challenged to change their ways, and their business model has not been subject to regulation that might promote competition and fight the spread of hate.

(Picture 1) Former Wisconsin Gov. Jim Doyle (remote, left) and Maureen Costello say that changes to education in all its forms are needed to fight racism. (Picture 2) David Williams points out the ill health effects that racism can have on students.

Sarah Sholes/Harvard Chan School

Young people are among the largest consumers of online content, and they are deeply affected by the broader social context around hatred and racism, said Maureen Costello, director of Teaching Tolerance and a member of the senior leadership team for the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Costello said incidents in schools, as in the nation more broadly, began to rise during the 2016 presidential campaign. Recent FBI statistics show that 25 percent of hate crimes nationally occur in schools, from kindergarten through college. Teachers at about that time reported that marginalized students were more anxious, a situation that subsequent studies have shown continuing. In addition, bullying was “weaponized” by the political debate, Costello said, and teachers were uncertain how to handle that.

Costello pointed out that 51 percent of American schoolchildren are from minority groups, and a fearful school environment can affect their ability to learn.

“You cannot educate when children don’t feel safe,” Costello said.

David Williams, Norman Professor of Public Health and chair of the Harvard Chan School’s Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, said studies show that even low levels of hate and discrimination have a negative effect on health, increasing the risk of anxiety, depression, and even premature death. Anti-immigrant rhetoric and police practices such as random stops have been shown to cause drops in health care use by people of non-European extraction, even when they are American-born, Williams said.

Panelists discussed ways to combat the rise. They pointed to improved police training and to consistent messaging that embraces tolerance in schools, reinforced by programs like a “mix it up at lunch day” that encourages students to sit with classmates they normally would not dine with, as well as training programs like Costello’s Teaching Tolerance, which trains teachers.

“It can’t just be a moment in the school year. In fact, schools are incredibly important places. They’re crucibles of building the society we’re all going to live in in 10 years or 20 years,” said Costello, who added that many schools are doing a good job on this front. “They are also one of the last common institutions standing. It’s a time that calls for more investment in making sure that schools are doing their jobs to counter hate and to build that good society.”

Doyle said it’s important that conversations on the topic continue, so voters understand the harm that racism causes and the hidden erosions of implicit bias, while being exposed to views of those who look different from them.

“In a democracy … that’s how we make sure the policies we want are effectuated,” Doyle said. “So it’s really critical that we have a very, very engaged political body…. And I’ll give President Trump credit for this: We have an engaged electorate like we’ve never seen before.”