Song of the sea

Photos by Johnathan Carr

‘Endlings’ playwright imagines lives both similar to and different from her own

Celine Song, whose “Endlings” begins previews tonight at the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.), knows how to create Korean characters. The playwright, a Korean Canadian, emigrated from South Korea with her parents at age 12, and her 91-year-old grandmother still lives in Seoul.

The greater challenge for Song — the key to writing what she considers her “impossible” play — was finding her own multifaceted voice, as an immigrant, a contemporary woman, and, she said, an “Asian Canadian married to a white American,” while striving to excel in a form defined largely by European-American men. That, she says, is what writing her new play, which is having its world premiere at the A.R.T. , taught her.

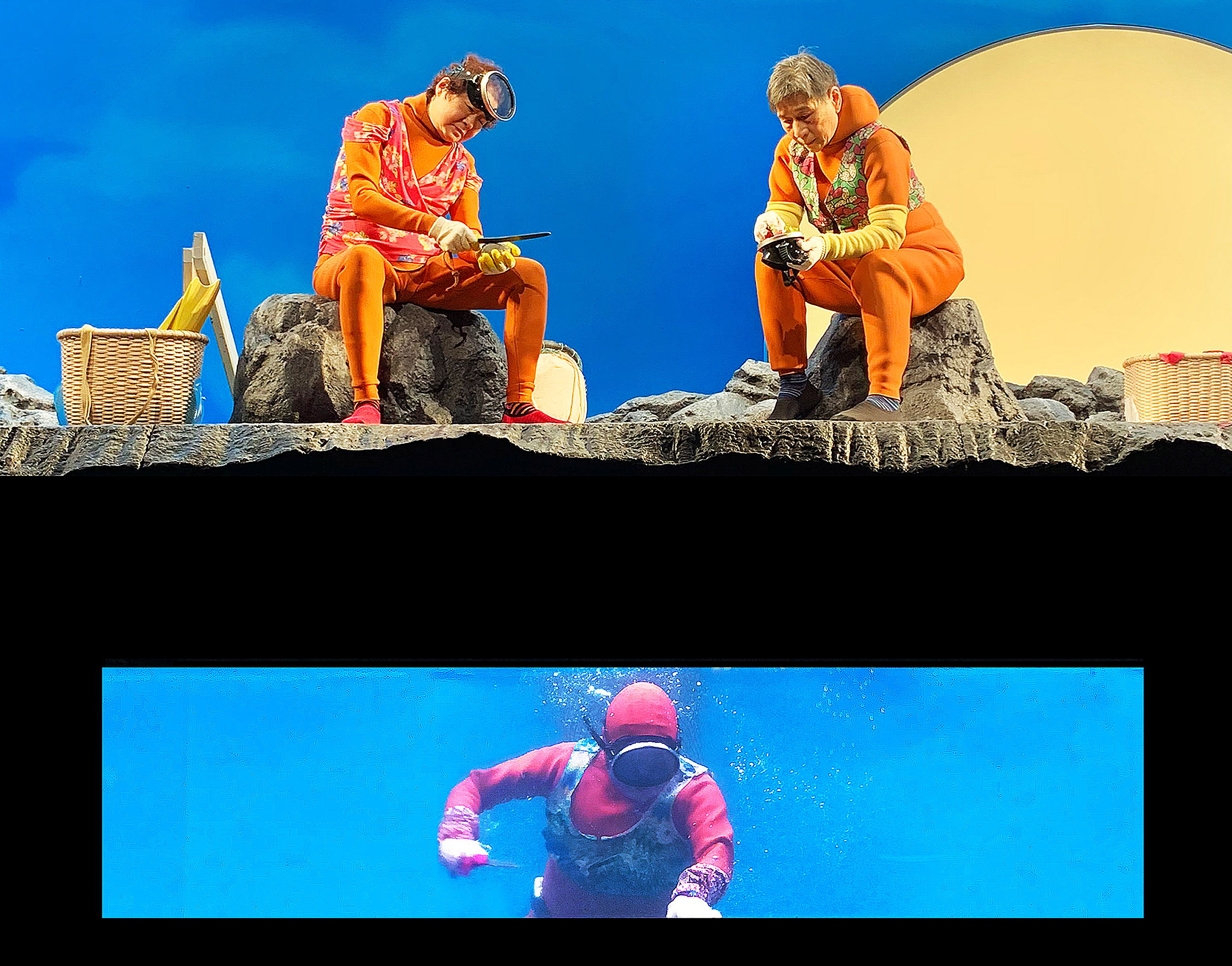

Not that the three elderly Korean women at the heart of “Endlings” are simple. Haenyeos — “sea women” — they are heirs to a centuries-old tradition of diving to harvest seafood off the Korean island of Man-Jae. Overtaken by technology, mechanization, fish farming, and the globalization of the food market, these women persevere despite knowing that they will likely be the last generation to practice their dangerous trade.

(The script calls for the haenyeo to perform both on land and under water. So the A.R.T. production features an onstage pool to bring that second environment to life as well.)

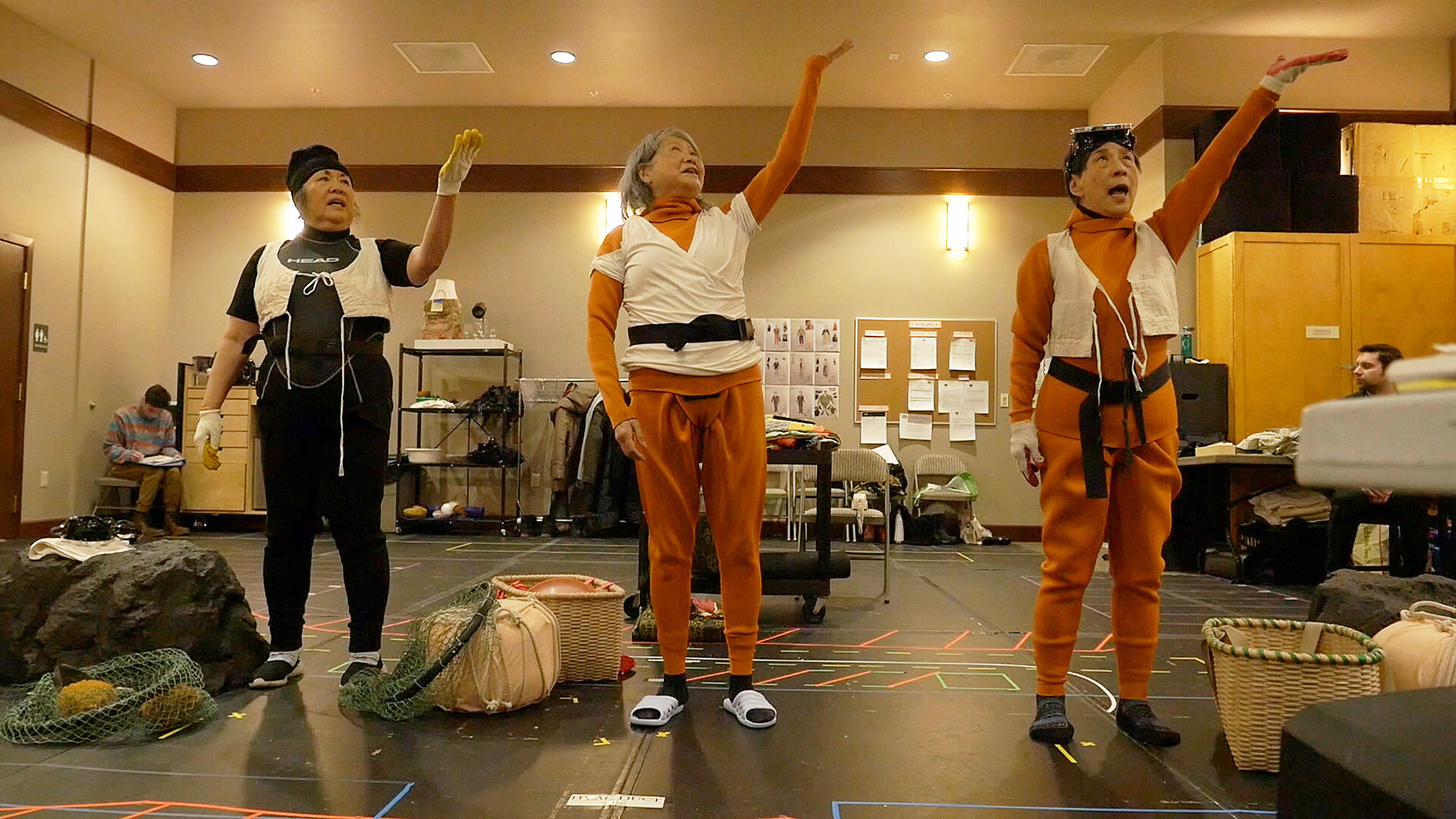

Emily Kuroda, Jo Yang, and Wai Ching Ho in rehearsal for “Endlings.”

Johnathan Carr

These women may seem a world — if not a century — apart from Song. However, while watching a documentary on the haenyeo, Song was struck by one diver’s similarities to her own family. At 97 years old, the woman “couldn’t really walk on land but could dive like a mermaid,” said Song. With the abalone and other seafood she harvested, she made about $3,000 each year, of which she sent $1,000 to her son, who had, like Song’s family, immigrated to Canada.

“I was thinking about how absolutely different we are but how tied I am — by ethnicity, by nationality,” said Song. At the same time, she added, “I have so much more in common with my husband, who is a white man who grew up in L.A.”

For Song, this is a story of time as well as place. “I have been thinking about my grandmother a lot,” Song said, especially about how the technology that brings people closer also emphasizes the differences between generations. “For me, a smartphone is a way of life,” said the playwright, while her grandmother “has trouble taking a photo.” The result is a temporal disconnect.

Photos by Jason Sherwood and Johnathan Carr

“I exist in my grandmother’s life as actively as I exist in New York City or L.A., in the writer’s room for a TV show,” Song said. “My grandmother and I are actively related to each other, but it doesn’t feel like we’re the same species.”

Song’s chosen media only complicates the issue of identity. “If you fall in love with theater, what that means is you’re going to fall in love with a lot of white men — Berthold Brecht, [Samuel] Beckett, Edward Albee, Wallace Shawn. And for a long time I didn’t want people to notice that I am an Asian woman. I wanted to be treated like and have the same privileges as the people I admire,” she said.

Prior to “Endlings,” Song had success. A semifinalist for the American Playwriting Foundation’s 2016 Relentless Award for her “Tom & Eliza,” Song has also been a Playwrights Realm writing fellow and a member of the Public Theater’s 2016–17 Emerging Writers Group. However, she often felt she was trying to “take on the white male voice.”

“I don’t think that I ever succeeded,” she said. “My voice was always there. But there was a way in which I was very afraid to open myself up.”

The problem, she concluded, is not specifically that she is Korean Canadian. But the many layers of experience — of place, heritage, and time — that make up her (and perhaps everyone’s) identity. “I wish I was authentically Korean in a way that was convenient to white viewers,” Song said. She mimicked a well-intentioned friend saying, “‘Hey Celine, you’re Korean, right?’”

“There’s a very small box that people want to put people in,” she continued. “Anybody, but specifically someone like me. … This play taught me the authenticity that I am seeking is not as neat and clean and one-thing as I feel pressured to be.”

“Endlings,” in previews at the Loeb Drama Center in Cambridge, formally opens on Friday, March 1, and closes Sunday, March 17. Tickets are available online at americanrepertorytheater.org, by phone at 617-547-8300, and in person at the ticket services offices, 64 Brattle St.