Diablo Cody wrote the book for the musical “Jagged Little Pill.”

Credit: American Repertory Theater

‘Jagged Little Pill,’ from songs to musical

Iconic ’90s album is adapted into A.R.T. show written by Diablo Cody

It became the soundtrack for a generation of young women.

A mix of anger, angst, heartache, and hope, the 1995 alternative rock album “Jagged Little Pill” was both a defining moment in pop music and a runaway success. It launched its creator, Canadian singer-songwriter Alanis Morissette, to stardom. This month, a musical adaptation inspired by the album and some of Morissette’s other work is premiering at the American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.).

Terrie and Bradley Bloom Artistic Director Diane Paulus will helm the production about a multigenerational family. Writer and producer Diablo Cody, who won an Academy Award for best original screenplay for the 2007 film “Juno,” wrote the show’s book and also a song for the score.

In the personal backstory below, Cody reflects on her deep early connections to the formative album, and on how she crafted a narrative from its iconic songs.

I was 16 years old the first time I heard the voice of Alanis Morissette. Well, technically that isn’t true — I grew up watching “You Can’t Do That on Television,” the Canadian kiddie show in which a young Alanis starred. But when I say “the voice of Alanis Morissette,” I’m not referring to the literal vibrations created by her laryngeal folds. I’m talking about the powerful and primal flow of essential Alanis-ness that is her legendary album “Jagged Little Pill.”

This was not just a collection of songs, you understand. This was a seismic event that shifted the plates of pop culture and redefined irony for a generation. Morissette, a rock star, was more than a voice. She was a Voice.

It was 1995, and I was hanging out in my bedroom in Lemont, Ill., a small town with nine churches and zero bookstores. I was listening to Q101, “Chicago’s Rock Alternative,” like I did every day after school. Though the grunge trend had expired like a tub of old yogurt, rock radio was still dominated by growling, lank-haired dudes with low-slung guitars and big muff distortion pedals. Kurt Cobain and Eddie Vedder had changed the game by championing feminist causes, but the rock scene in general still felt like the same old macho stance it had been forever. The “girl bands” that did get airplay at the time were all punk bravado and defiance — very necessary, but not always relatable to me as a vulnerable and confused Catholic girl who had so many feelings and was often afraid to express them. There was an Alanis-shaped hole in my heart; I just didn’t know it yet.

So there I was, in my bedroom, flipping through Sassy magazine and painting my nails with Wite-Out as I listened to the radio. As the song ended — let’s say it was “Cumbersome” by Seven Mary Three — the DJ broke in, sounding way more enthusiastic than usual. “I am so psyched to play this next song,” the DJ said. Again, this type of editorializing was rare on Q101, a big corporate radio station. “It’s from a new singer named Alanis Morissette, and it’s going to blow your mind. Here’s ‘You Oughta Know.’ ”

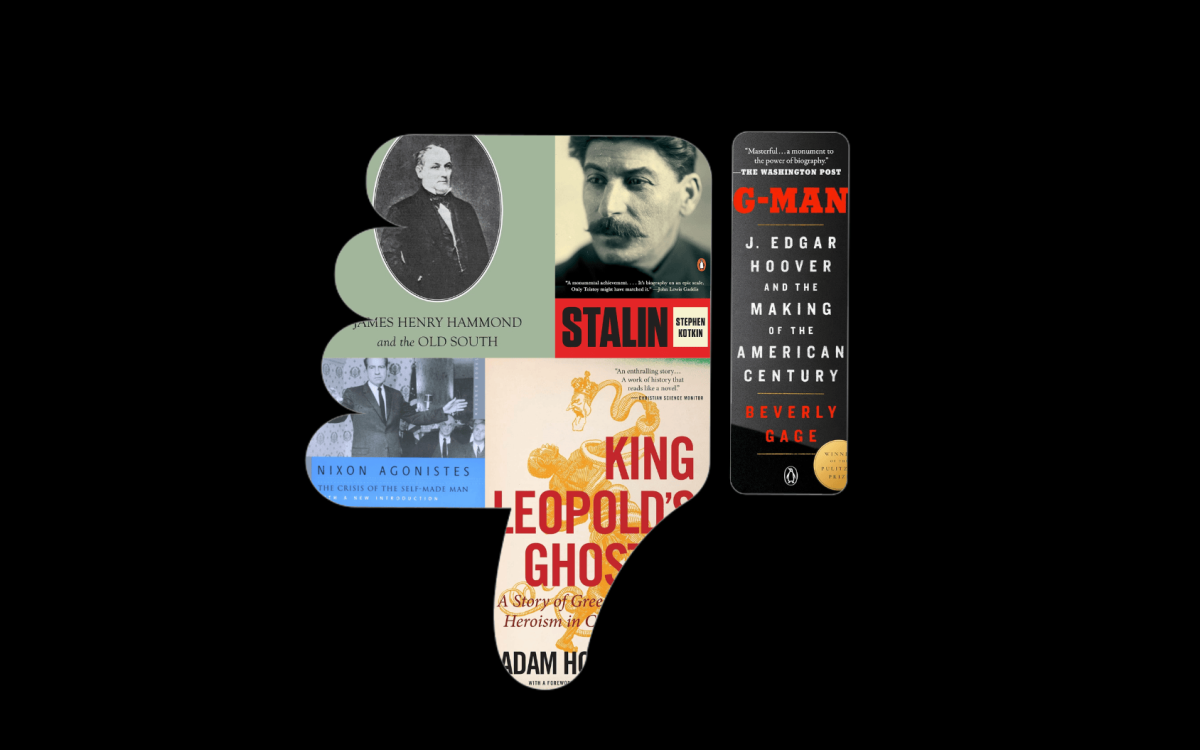

Laurel Harris, Soph Menas, Elizabeth Stanley, Nora Schell, and Logan Hart perform songs from “Jagged Little Pill” at the A.R.T. Gala on March 5, 2018, at the Boch Center Wang Theatre.

Credit: Gretjen Helene Photography

Curiosity piqued, I twisted the volume knob on my Sony boombox. A trembling voice filled the room — not just a voice, but a Voice: Alanis’ brave, forceful, naked Voice revealing itself for the first time. It was an immediate shock to the system. After a parade of grunge singers cocooning themselves in flannel and mumbling purposely vague lyrics, here, at last, was someone ready to expose her soul.

And “You Oughta Know” was just the beginning — the beginning of the beginning. As we would soon discover, there was so much more to this artist than just spite and rage. On “Jagged Little Pill” she revealed herself to be tender, spiritual, shameless, kindhearted, eternally questioning, and utterly assured all at once. Shockingly, Alanis was only 19 years old when she wrote these songs with producer Glen Ballard — just a skip ahead of me, agewise, but miles beyond in terms of artistic maturity.

Flash-forward 23 years later: Many other seminal ’90s albums feel preserved in amber: beloved, certainly, but with their vitality confined to the era. But “Jagged Little Pill” somehow is more relevant than ever. It’s an album that tells us to wake up, “swallow it down,” and confront our fears. Most popular music encourages the pursuit of pleasure; “Jagged Little Pill” actually recommends discomfort. These songs suggest that we subject ourselves to that which hurts (and ultimately heals), that we debride our deepest wounds, even though the process itself can be excruciating. This type of therapeutic instruction continues to be a theme in Alanis’ music to this day, and yet somehow her songs never feel gloomy or pedantic. Actually, they feel euphoric. How?! It’s a miracle that Alanis performs over and over. No wonder Kevin Smith cast her as God in “Dogma.”

“Jagged Little Pill” was the soundtrack to my 17th summer and has become even more meaningful to me as I head into my 41st. Back in 1995, I never could have imagined I’d someday be tasked with creating a narrative around Alanis’ incredible catalog of songs. Like the music itself, the job has been challenging bliss. Working on this show, I am often struck by how inherently theatrical the music is, even before it’s been rearranged for the theater. The romance, laughter, tears, sex, and loss are already there, embroidered into the lyrics and melodies. I am incredibly proud of my role as translator and midwife in this production. If I’m lucky, I’ll make one of my heroes proud in the process.

Diablo Cody is the writer of the book for the musical “Jagged Little Pill.” Her work includes “Candy Girl: A Year in the Life of an Unlikely Stripper,” “Juno” (Academy Award, BAFTA Award), “United States of Tara,” “Jennifer’s Body,” “Young Adult,” and “Tully.”

This piece was written by Diablo Cody for the American Repertory Theater’s Guide and reprinted with permission.

“Jagged Little Pill” opens in previews at the A.R.T. on May 5.