Jill Lepore (from left), Jeannie Suk Gersen, and Evelynn M. Hammonds take part in a panel discussion during a conference about the #MeToo movement at the Radcliffe Institute.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Probing the past and future of #MeToo

Scholars at Radcliffe session examine the deep meaning of a movement

More like this

In October, accusations of sexual assault against movie mogul Harvey Weinstein sparked a wave of allegations against other high-profile men in the media and beyond and powered a social movement demanding change.

But what seems like a new cultural conversation to some has been years in the making. Even the phrase that has defined the movement, captured in the viral internet campaign #MeToo, was born long before the Twitter and hashtag rage. Activist Tarana Burke first used “Me Too” for the name of her 2006 crusade to raise awareness about sexual assault.

The movement’s roots and its present and future impact were the focus of a discussion with Harvard scholars on Monday night at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, organized by the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America and moderated by Ann Marie Lipinski, curator of Harvard’s Nieman Foundation for Journalism.

The event also aimed to look ahead “to new directions in feminism, social movements, employment law, and of course in campus life,” said Jane Kamensky, the Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation Director of the Schlesinger Library.

David Laibson, who was part Harvard’s Task Force on the Prevention of Sexual Assault and helped design a campus climate survey distributed to 20,000 students in 2015, addressed its findings and some of the challenges facing higher education. The survey results said that of the more than 60 percent of women in the class who responded, 31 percent said they had experienced some sort of unwanted sexual contact.

Students on a college or university campus may worry that reporting an assault will harm their friendships, their standing in the community, or even their relationship with doctoral advisers who often have “enormous power over that person’s future,” said Laibson, the Robert I. Goldman Professor of Economics.

Evelynn Hammonds, the Barbara Gutmann Rosenkrantz Professor of the History of Science, noted that “black women’s intersectional experiences of racism and sexism have been a central but often forgotten dynamic in the unfolding of feminist and anti-racist agendas,” and she urged listeners to remember the women from any background, race, or class who want their stories heard.

“When we talk about reporting, we have to take into account the different locations of the women and all people who are victims of sexual assault. We have to tell a more complicated story, provide more strenuous pathways for people to speak.”

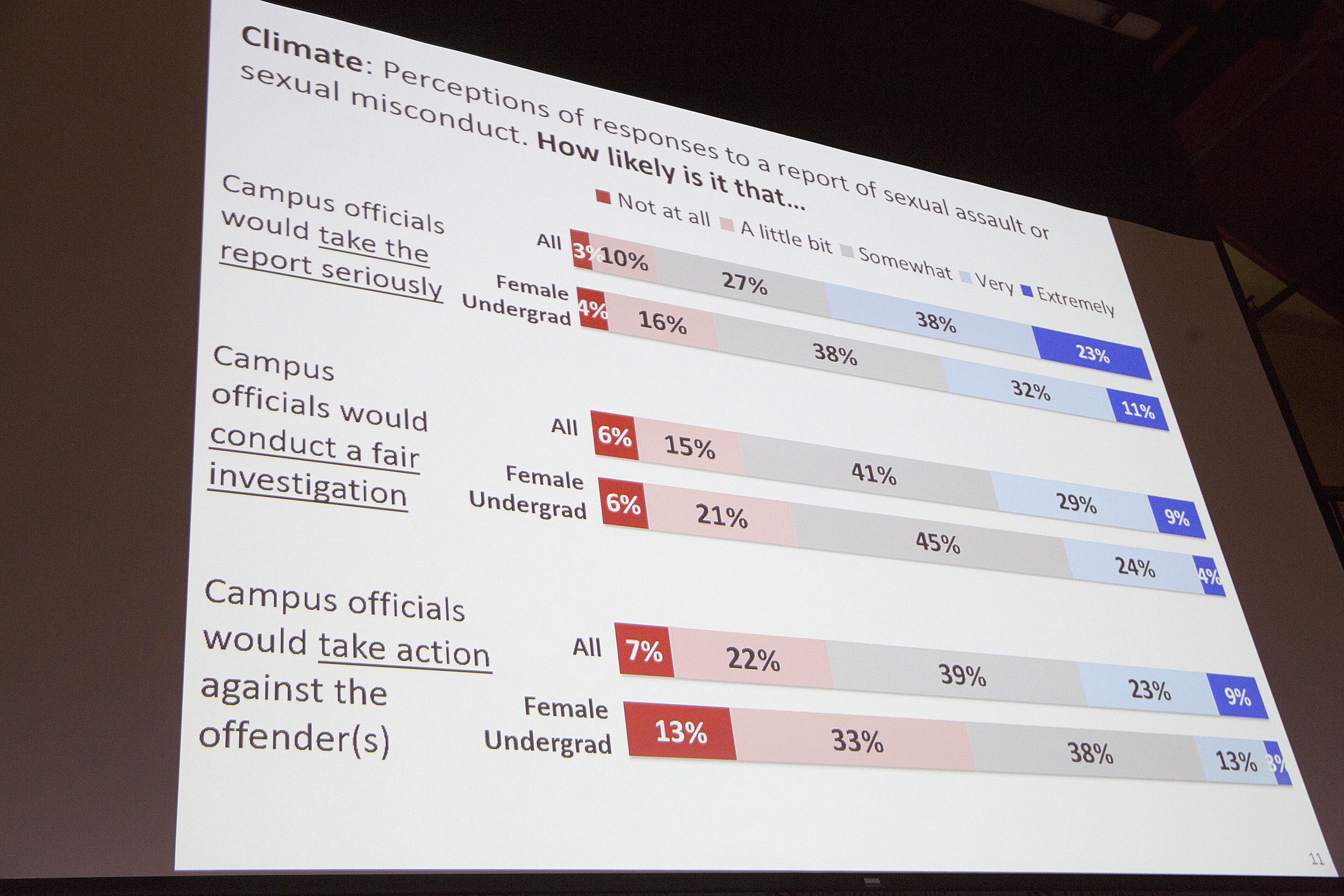

A presentation slide shows stark disparities in how female undergraduate students perceive charges of sexual assault will be handled by university officials compared to the student body at large.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

With her eye on history, Jill Lepore, the David Woods Kemper ’41 Professor of American History, said the oft-cited generational divide between older and younger feminists is a manifestation of a longstanding rift in the women’s movement between the protectionists, who are eager to hold on to special rights gradually gained for women over time, and the equalizers, who push for a more sweeping, equal-rights-for-all agenda.

It can be helpful to remember that this deep divide “is with us still,” said Lepore, noting that many people opposed to the direction of Title IX litigation and #MeToo see such efforts as protectionist in nature.

Lepore also recalled the campaign against sex criminals in 1937 by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover used the effort as a political tool to push aside people “with the act of scandalizing their private affairs,” and helped usher in McCarthyism, said Lepore. She called the effort a cautionary tale for the #MeToo movement.

“I almost in a way hate to raise the specter of such a terrifying and fearsome piece of American political and social and sexual history, but I do think it’s the kind of story that we do need to face as we try to determine the future direction of a movement that could lead to lasting change and real justice, but could equally well — and history might suggest [would] — lead to something itself quite terrible.”

Jane Kamensky holds up a Time’s Up pin for the audience to see.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

For Harvard Law School’s Jeannie Suk Gersen, recent statements from U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg point to another divisive debate. Asked about the #MeToo movement in a recent interview, Ginsburg said due process must not be ignored. Gersen, the John H. Watson Jr. Professor of Law, agreed.

“One of the salient, and in my mind, very unfortunate aspects of the current moment is how a commitment to due process or fairness has become associated with one side, with men’s rights, with Betsy DeVos and her decision to rescind the Obama administration’s policies on Title IX,” which protects people from sex discrimination in education or other programs receiving federal aid, said Gersen.

She echoed Ginsburg’s assertion that “the commitment to gender equality and to procedural fairness have to go together.” Due process, added Gersen, is “for guilty people and innocent people alike. It is overall about the legitimacy of the system that we can believe in.”