Then-candidate Donald Trump speaks at a Texas campaign rally in 2016.

Photo by Gerald Herbert/AP

Trump’s language, unseemly to critics, reassures his base

First as candidate and now as president, his word choices and stances are regularly directed at the worried working class, professor says

One of the most unusual aspects of President Trump’s unconventional presidency is his distinctive speaking style. It’s a caps-locked world of mixed syntax, offbeat grammar, malapropisms, slang, exaggerations, pet phrases, and “us versus them” contrasts. Nonetheless, the way he communicates proved a powerfully effective draw for many voters during the 2016 election.

His communications style has come under renewed scrutiny following the recent publication of the dishy best-seller “Fire and Fury” and the derogatory remarks he reportedly made to members of Congress about Haiti, El Salvador, and African countries.

Since the start of his presidential campaign, Trump’s colloquial, often strident speaking approach has proven unusually polarizing for a politician who would be elected to govern a nation of 325 million. What many listeners find authentic and unpretentious, others find coarse and off-putting.

Sociologist Michèle Lamont, the Robert I. Goldman Professor of European Studies and professor of African and African American studies, believes that, from early in his candidacy, Trump’s word choices signaled a deliberate effort to court supporters without college degrees, including working-class whites and those in lower-paying jobs such as retail sales or bank services, the very subset of voters who overwhelmingly turned out to put him in office.

Lamont, director of the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, extensively studied the white working class in the United States and France for her book “The Dignity of Working Men” (Harvard University Press, 2000), and when Trump stepped onto the political stage, his pitch instantly sounded familiar to her.

Recalling her interviews with earlier subjects, “I knew that they defined themselves as the people who keep the world in moral order. That’s done in part by this notion of ‘providing and protecting’ women,” she said. Also, “They drew very strong boundaries toward African-Americans and the poor, mostly by emphasizing the lack of ‘self-reliance’ of these groups.”

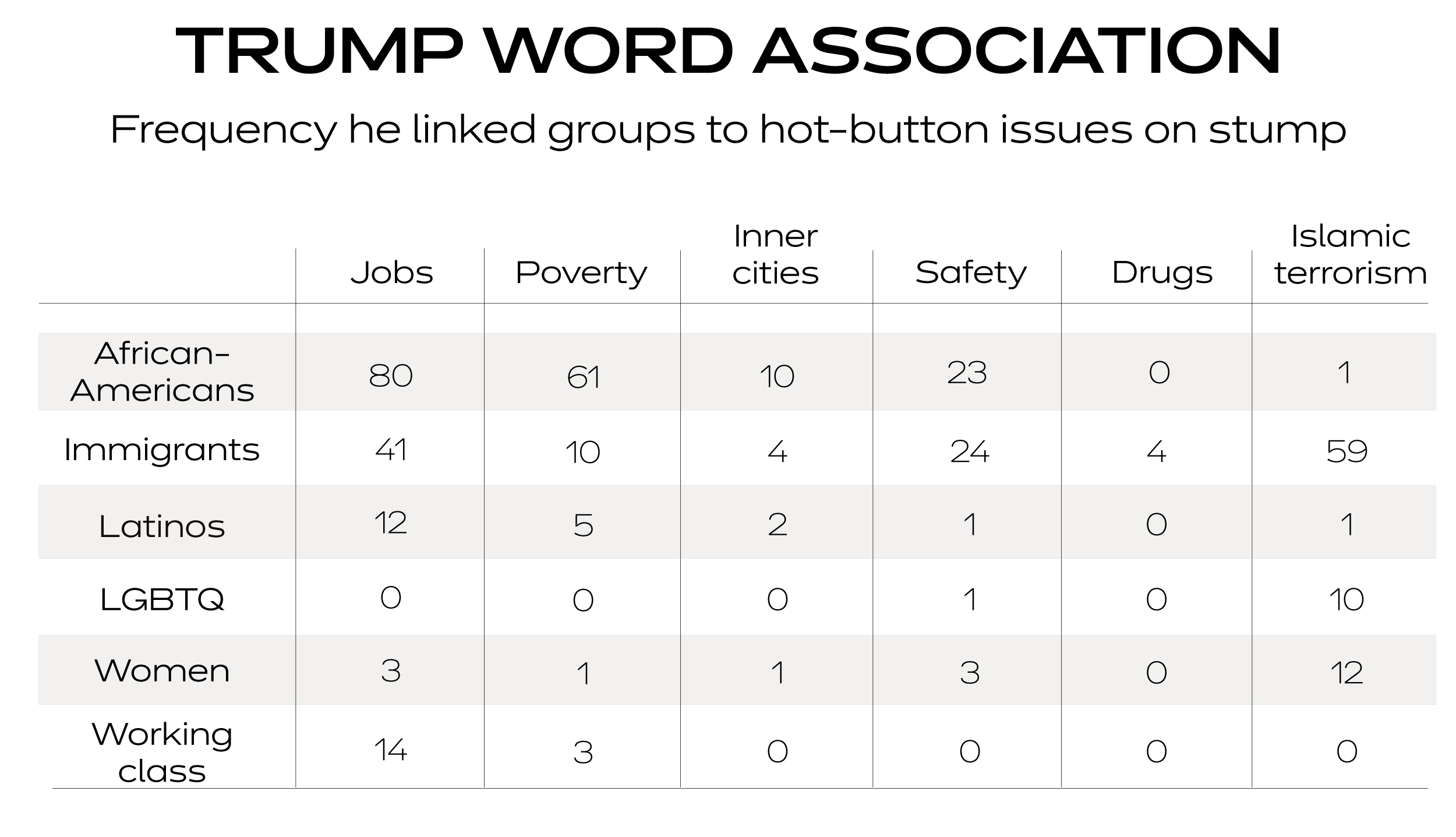

To understand better how the president’s use of political rhetoric resonated with these voters (and, by the way, generally continues to do so), Lamont and Harvard graduate students Bo Yun Park and Elena Ayala-Hurtado examined 73 formal speeches Trump gave during the campaign. In a paper published in the British Journal of Sociology, they focused on references to social groups such as refugees, Latinos, and Muslims, and the topical contexts in which those words were used, such as safety and jobs.

Source: “Trump’s electoral speeches and his appeal to the American white working class,” Michèle Lamont, the Robert I. Goldman Professor of European Studies and professor of African and African American studies

Instead of analyzing Trump’s word choices through traditionally narrow lenses of race or ethnicity, for example, Lamont said they looked at how his rhetoric reinforced a broader theme of exclusion by emphasizing the boundaries that working-class whites perceive between themselves and others, whether racial, ethno-national, educational, socioeconomic, or religious.

“We could immediately see how he was appealing to workers by talking about blaming globalization, saying he was going to give [them] jobs” — and not just white workers, but African-Americans and Latinos too, Lamont said in an interview. “His populist argument was oriented toward appealing to all workers, but at the same time, he was [engaged in] veiled racism by talking about ‘the inner city’ and things like that.”

Though all politicians try to use words and phrases to inspire voters to support their ideas, Lamont said that Trump’s speeches show his expert marketing instincts at work. His disparaging references in speeches to immigrants, Muslims, and Mexicans who immigrated illegally, along with his assertion that African-Americans were predominantly poor and living in gang-ravaged cities, were strategic “red buttons” that resonated with his white working-class base. The language was both explicit and implicit, she said, designed both to reinforce the social boundaries his base perceived between themselves and other groups and to validate their attitudes about their own inherent worth and the values they believe distinguish them from others.

Trump’s remarks about women and LGBTQ people centered on an argument that they needed “protection” from violent immigrants, especially “Muslims,” a term he used as a stand-in for radical Islamists, she suggested. Though he sometimes spoke positively about women, saying he was “surrounded by smart women,” Trump also “talked about them as people who need to be protected and provided for, which is very much appealing to the traditional ways workers assert their own worth, because it’s one of the dimensions of working-class masculinity — to be providing for and protecting women and family,” said Lamont.

People tend to make sense of their social world by putting themselves and others into groups based on perceived commonalities and differences, such as ethnicity, race, religion, gender identity, sexual preference, and socioeconomic status. These boundaries function as a way to define who belongs to a particular group or strata and who does not. In the paper, Lamont noted that one of the more effective strategies Trump employed was to recognize the important role that dignity plays among the white working-class and seize on its power by blaming the economic inequality and unemployment they’ve experienced on globalization, rather than on a lack of education, training, or other factors.

“For the working class to find themselves with no job is both an economic tragedy and a cultural tragedy, since their self-concept is very much about being hard-working. So by telling them, ‘It’s globalization, and it’s the people who pushed globalization, such as Hillary Clinton, who are responsible for your downfall,’” Trump directed their anger outward and removed them from responsibility for their life circumstances, she said.

“We have to remember, many workers, they want to think of themselves — and they are — as extremely hard-working, and they want jobs. … He’s trying to give them their dignity back by saying, ‘I know that you’re hard-working people, and you’re capable of doing this.’”

Lamont disagrees with the contention that Trump’s election was driven by economic anxiety or by racial resentment. Rather, she sees the outcome as more nuanced, involving a debate over status positioning. “The sense of status hierarchy that people are defending has to do with both cultural resources — that is, who is viewed as the legitimate citizen, who has cultural membership, who defines what mainstream America is about — but also about economic resources,” she said. “So it’s both at once.”

One way that academia can help bridge political divides and social boundaries in this country and pierce information echo chambers is to work on some of these issues in a cross-disciplinary way, said Lamont.

“I think social scientists really need to take on a dimension of inequality that has not been studied as much as the unequal distribution of income and wealth, which is this process of recognition by which groups develop their sense of worth,” she said. “That’s very much my agenda moving forward.”