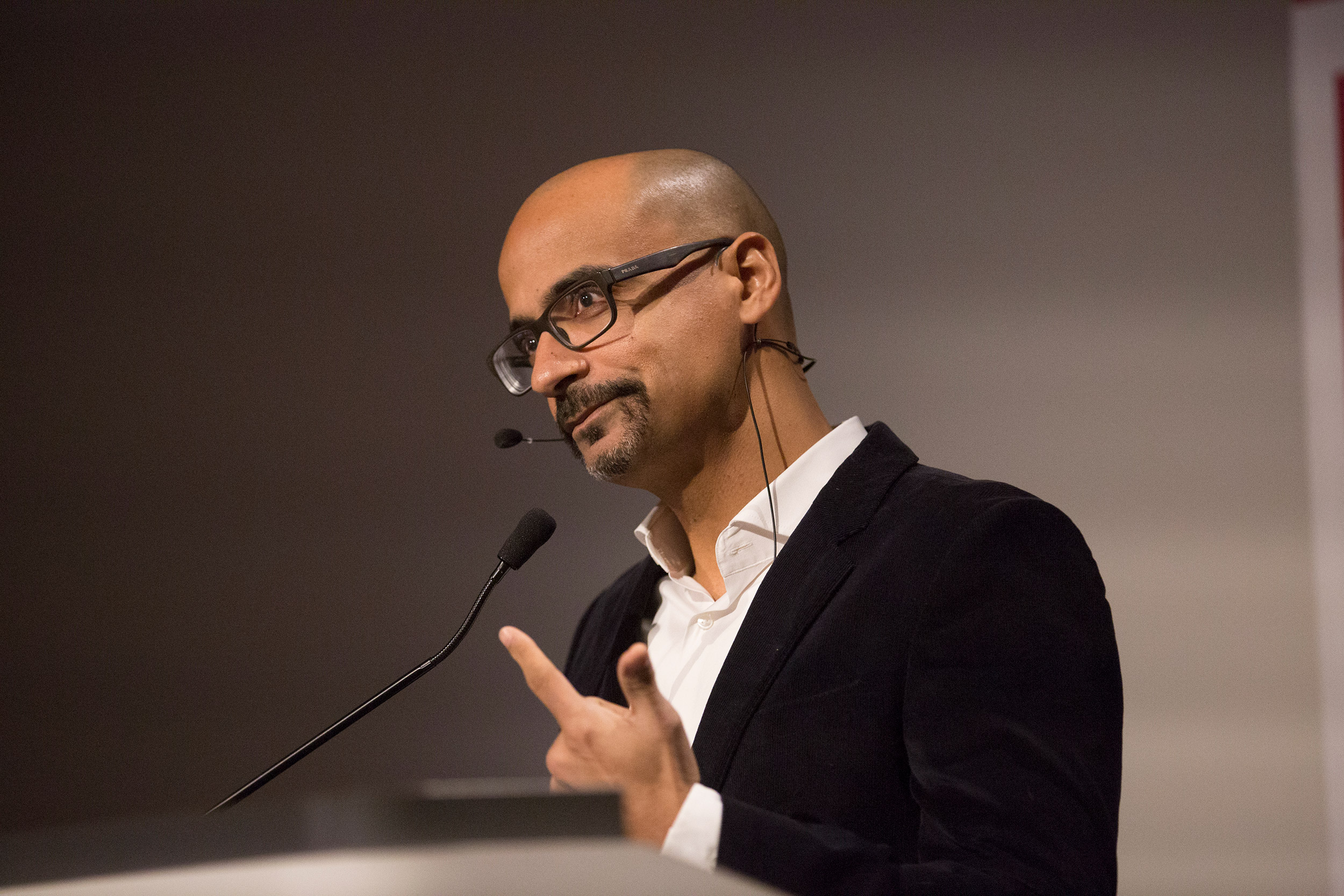

Writer Junot Díaz speaks at the “Migration and the Humanities” conference. “It’s no accident that the folks who could most tell us about global conditions are being silenced in such profound ways,” he said.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Junot Díaz gets personal — and political — at Harvard conference

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist brings multiple identities to ‘Migration and the Humanities’

“You don’t have to be a Harvard student to be aware of what’s happening with migration and immigration.” With that nod to his audience, novelist Junot Díaz launched a freewheeling evening of reading and discussion Thursday at the Graduate School of Design’s Piper Auditorium.

Awareness of these issues is key, said Díaz, whose “Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao” won a Pulitzer Prize in 2008.

“It’s no accident that the folks who could most tell us about global conditions are being silenced in such profound ways,” he said. “This increases our lack of understanding about what is going on.”

The author, who is also a professor of creative writing at MIT, was speaking at the inaugural Migration and the Humanities conference, sponsored by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. His talk and an ensuing discussion with New York Times book critic Parul Seghal and Homi Bhabha, director of the Mahindra Humanities Center, followed a musical interlude by a trio from the Silk Road Ensemble, with Edward Perez ’00 on bass, Martin Thomas ’18 on viola, and Hadi Eldebeck on oud. The music drew from multiple cultures.

“Migration is a central and even a defining issue” of our time, said Harvard President Drew Faust in introductory remarks. “The right of movement is one of the most fundamental of human rights.”

For Diaz, “an immigrant from the Caribbean,” the political is personal. “I’m really interested in the ways that my multiple identities are playing out,” he said, in “this global anti-migrant, anti-immigrant mood.”

For his reading, Díaz picked a short story called “The Money.” Narrated by a young Dominican-American, the piece, which originally ran in The New Yorker, deals with property and security, the debt newcomers owe to the people they’ve left behind, and a young boy’s expectations of both his new American friends and the family who brought him here.

Opening the discussion, Seghal — an Indian-American whose parents were Partition-era refugees — talked about how migration narratives have changed.

Image 1: Homi Bhabha and New York Times book critic Parul Seghal engaged in a discussion. Image 2: President Faust opened the conference before Diaz’s address, declaring “The right of movement is one of the most fundamental of human rights.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

“For a very long time, there was this idea that the drama was the immigrant coming to this country, and, however reluctantly, adjusting to it,” she said. “In the last 10 years a very different kind of note has entered literature.” Describing the new focus as “much darker,” she mused that this new focus is “not what do we do with these refugees in our midst, but what creates them?”

“Migration,” she noted, citing writers such as Salman Rushdie on place and identity, “is a kind of death.”

This experience, and how it can skew an individual’s sense of self, is also what engages Díaz. He observed how his students, like many of his fictional characters, try to carve out authentic identities while being buffeted by violent or hypersexual stereotypes.

“A community that can’t generate a lot of love is emblematic of a community with a lot of trauma,” he said. Ultimately, his work — and the questions facing a world in which so many people are on the move or displaced — must ask itself: “How do we survive the surviving? How can we create healthy intimacies?”