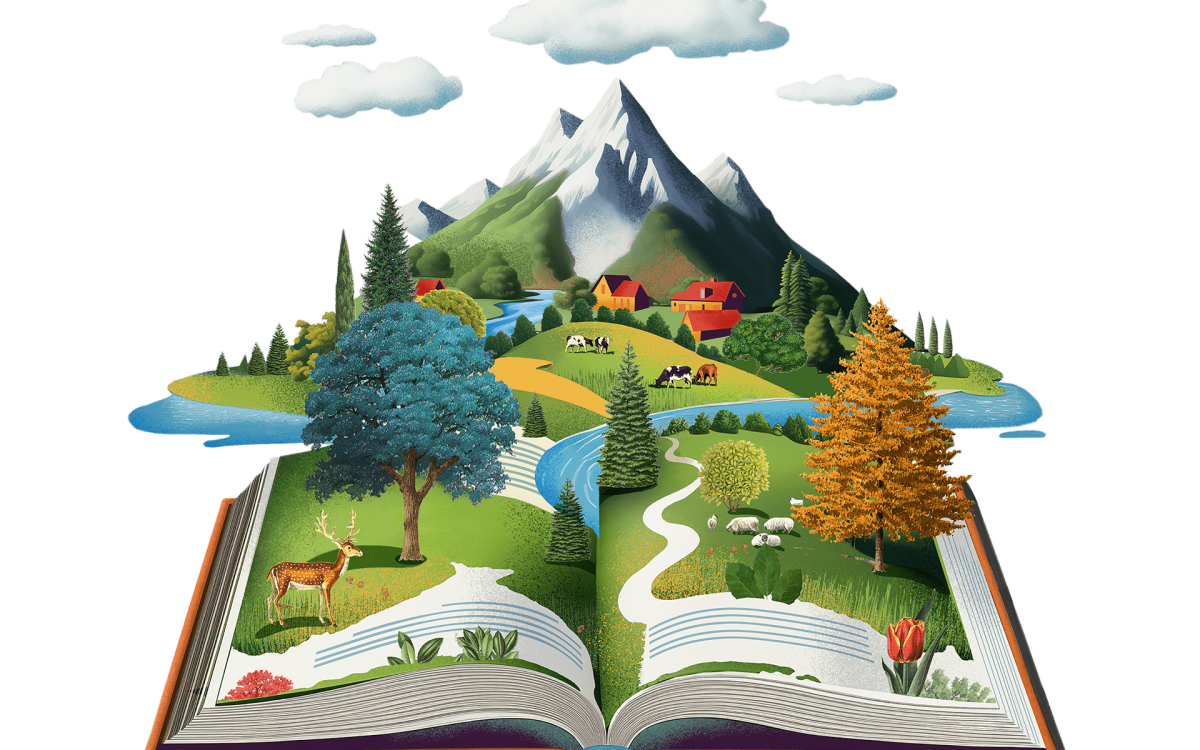

Outside the Yuchi House in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, a student sounds out the words on a stop sign informing students and visitors that English is not to be spoken on the premises.

Courtesy of the Euchee/Yuchi Language Project

Preserving a culture, one speaker at a time

Yuchi Language Project seeks to revitalize indigenous identity through common tongue

Thousands of indigenous languages are in danger of disappearing before the end of the century, including most of those spoken in North America, according to a report from UNESCO. This is part one of a two-part series of discussions with Native American language preservationists and their efforts to revive their ancestral tongues.

When Richard Grounds began the Euchee/Yuchi Language Project (ELP) in 1996, it was no light undertaking. Grounds wanted nothing less than to prevent his tribe’s cultural extinction, and he knew he must start with its words.

“We are an original people,” he said. “Our elders tell us our language is a gift from the Creator, and it is our special responsibility to care for that gift and pass it on to our children.”

The Yuchi people, also known as the Tsoyaha , traditionally inhabited eastern Tennessee, though their origins remain a mystery and their language is a linguistic isolate that does not resemble any other Native American tongue. During the 17th century the Yuchi moved south, and in the 1800s they were forcibly relocated to Oklahoma, currently one of the worst regions for language loss. A concerted assimilation effort after World War II saw thousands of Native American children enrolled in boarding schools where they were only allowed to speak English, and could be punished for using their native languages. Like many indigenous peoples, the Yuchi came close to losing their language in a single generation.

Grounds, who delivered the 2015 Greeley Lecture at Harvard Divinity School and returned this year to participate in the School’s Native American Speaker Series, does not believe this was unintentional. For centuries, the U.S. government, academics, and settlers told Native American tribes that their culture was on the brink of extinction, and treated them accordingly. Yet it only became a reality when they were prevented from learning their languages.

Before the first Europeans came to the Americas, thousands of native languages were spoken across the continent. Today only about 150 remain, and three out of four are spoken exclusively by people born before World War II. When Grounds began his program there were fewer than two dozen fluent, first-language speakers of Yuchi, and all of them were grandparents of non-speakers. Only three remain, each over 90 years old.

Today’s parents grew up hearing their grandparents speak Yuchi, said Grounds, but did not learn or pass it on to their children. “What we’re fighting against is a sort of internalized colonialism. People have been anaesthetized to the value of their language.”

Growing up, Grounds remembers his grandmother speaking Yuchi to him and his siblings, but as children of non-speakers, they never picked it up. “We had a feel for the language, maybe a few words and phrases, but we were never fluent,” he said. Grounds went on to learn several languages, passing graduate proficiency exams in French, German, Greek, and Hebrew, “But there was no funding to learn the language of my grandmother. It wasn’t important on the scale of European intellectual history.”

Grounds sought out elders and learned Yuchi from them, but he knew that few of his tribespeople would have the privilege, time, and energy to do the same. With the help of the elders and concerned Yuchis, Grounds founded the ELP as a nonprofit to pay for student transportation and class materials. But because the Yuchi are not a federally recognized tribe, there is little reliable funding available to the program. It relies heavily on grants and donations.

Centered around the Yuchi House — “more or less a hothouse for growing and teaching the language,” Grounds said — the ELP provides immersion classes for Yuchi children of all grades, free of charge. Community classes for curious adults are also offered.

“Maybe they spoke as kids and they want to pick it back up now that they’re adults, but they’re not ideal candidates,” Grounds said of the adult students. “The ideal situation is to get to them before they learn English.”

The sense of hope in the Yuchi community is matched only by the sense of urgency. Not only have nearly all their native-speaking elders died, but none of those who remain live particularly close to each other. Simply getting them to and from classes can take more time than the classes themselves, Grounds said.

The program has been able to make a few adults fluent enough to teach the roughly 60 enrolled children, but the gap between the last generation of first-language speakers and the next is so large that the program will be dependent on second-language speakers for many years to come.

To make matters worse, Yuchi is a notoriously difficult language to learn. It has no known relative to compare with; it is agglutinative, so an entire sentence can be contained in one verb; glottal stops are integral, drastically changing the meaning of words that sound homonymic to an untrained ear; it is not only gendered but has different registers for men and women, and different pronouns for tribespeople and non-Yuchis.

Like many Native American languages, Yuchi originally had no orthography, or standard written language. Linguists in the 20th century attempted to decode the language, but were unsuccessful until a phonetic transliteration was created in the 1970s. Grounds designed the orthography specifically as a teaching aid — the native-speaking elders do not use it outside of the classroom — knowing that there was little room for phonetic ambiguity.

“The underlying concept of the writing system was to use something that would require minimum stretch for kids who were just learning to read. We had a linguist come in and pretty heavy-handedly insist on a direct IPA [International Phonetic Alphabet] system,” he said. But it would have meant that the kids would be learning that the letter E sounds like “eel��� at public school but “hey” at Yuchi House. “For the sake of young learners, we needed to minimize the shift from their already nascent expectations, [so] we went with one symbol/one sound.”

He also wanted it to be easily typed, which is how the (@) symbol found its way into the Yuchi alphabet. Written Yuchi uses capital and lowercase letters to differentiate between long and short vowels, respectively, but there was still an odd sound out. In IPA, the A sound in words like “bat” or “cap” is represented by a grapheme called “ash” (æ). Æ is an official letter in a few North Germanic languages, and was used in most English-speaking countries until the 19th century, but fell out of favor when it was omitted from the first typewriter keyboards for space.

Needing a symbol to represent the æ sound, Grounds looked at his keyboard and realized the answer was literally under his nose. It even kept with his desire to keep the letters intuitive. What better letter to signify the A sound in “at” than the symbol that means “at”?

“It turned out to be very functional,” said Grounds. “Now kids are texting each other in the language.”

The result of these efforts may seem modest, Grounds concedes, with the number of fluent Yuchi speakers up to just 16, but the real successes are less quantitative. In addition to daily after-school classes for children in grammar school, the ELP has started working with toddlers to create a new generation that speaks Yuchi before learning English. Grounds’ own grandson is the first child raised speaking only Yuchi in nearly 70 years.

“The cultural health of our community is measured by the status of our language. It really matters in terms of our young people growing up as confident, healthy, self-fulfilled people who are able to succeed in life. It matters that they be grounded in their culture and their traditions, and nothing does that like knowing the language and being able to speak to the elders,” Grounds said.

“We literally think of it as keeping the world spinning.”