Depths of slavery, heard, seen, and felt

Scholars’ film on 18th-century Harvard debate gains power from poetry of Phillis Wheatley

At the age of 8, Africa-born Phillis Wheatley was kidnapped and sold into slavery. The property of a wealthy Boston family, she could read and speak English 16 months later. By 14, she had mastered Latin, likely knew Greek, and was familiar with astronomy and math. In 1773, at the age of 20, she published her first book of poetry, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral.”

“She was the mother of the African-American literary tradition,” said Henry Louis Gates Jr., the Alphonse Fletcher Jr. University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center, during a recent discussion at the Harvard Art Museums. But she was also “doomed to fail because of the structures of racism embedded even in the discourse of the Enlightenment,” he added.

While Voltaire and Washington praised Wheatley’s poetry, Thomas Jefferson, said Gates, called her work “beneath the dignity of criticism.” Her authorship of the volume was challenged by those who denied that a slave could have crafted such moving verse.

Today her work is part of a searing film, “No More, America,” that depicts an 18th-century Harvard debate about whether slavery was compatible with natural law. The 14-minute work, on view in the Harvard Art Museums’ Lightbox Gallery, was developed by Professor Peter Galison in conjunction with “The Philosophy Chamber: Art and Science in Harvard’s Teaching Cabinet, 1766-1820,” an exhibit highlighting the diverse teaching methods and fine art for which the Harvard Hall room was known.

The teaching cabinet was also a place for debate, often filled with the “voices and ideas that animated Harvard’s 18th-century history,” said Ethan Lasser, Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. Curator of American Art.

Some of that history is shadowed by slavery.

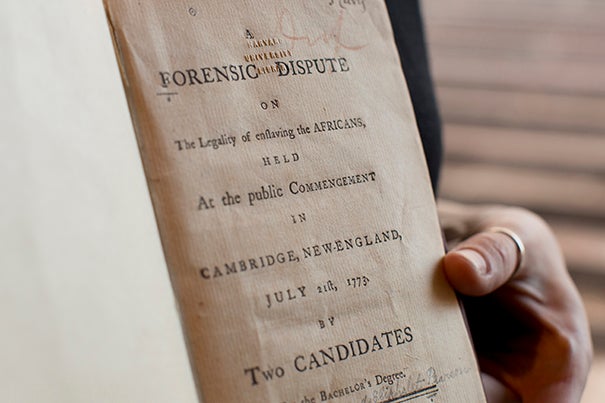

While conducting research for the exhibit, Lasser and his colleagues uncovered the only surviving transcript of the various student discussions the room hosted: the 1773 slavery debate between seniors Theodore Parsons and Eliphalet Pearson.

Galison’s portrayal of the exchange, said Lasser, offers up “new ways of thinking about the exhibition,” and about Harvard’s ties to slavery, which have been explored on campus in recent years.

Last year, President Drew Faust was joined by U.S. Rep John Lewis in affixing a commemorative plaque on Wadsworth House in honor of four slaves who worked there during the 18th-century presidencies of Benjamin Wadsworth and Edward Holyoke. In March, Faust spoke at a Radcliffe symposium on slavery and universities that featured the work of a number of Harvard faculty and students. Last month, Faust was joined by Annette Gordon Reed, the Charles Warren Professor of American Legal History and a professor of history, at the unveiling of a Harvard Law School memorial to enslaved people whose efforts helped found the School.

Galison, who directs the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, from which “The Philosophy Chamber” borrows, was asked by Lasser for a film idea inspired by an object from the collection. Instead, he turned his attention to the slavery debate, enlisting Gates, author of “The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America’s First Black Poet and Her Encounters with the Founding Fathers,” as his co-director.

Simply re-creating the 1773 Commencement debate would have been “morally impossible,” Galison said. Including Wheatley’s work helped deepen the engagement with slavery, he said, with the writer’s voice representing “the real presence, the moral presence of slavery in Harvard Yard.”

Gates’ interest in the poet largely stems from “this discourse between what I call race and reason: that somehow black people had to show that they were equal, somehow they had to demonstrate that they were fit by God or by nature, depending on where you stood, to be more than slaves because they possessed reason.”

Galison said that the film was inspired by a need to understand “how these words felt at the time.” Things that are said or that can be heard, he added, “have a different kind of power, and I think exploring them [through film] adds a dimension to our grasp of the world around us.”

The final product was a true collaboration. Harvard undergrads in the three roles received advice from members of the American Repertory Theater, and the score — by 18th-century composer Chevalier de Saint-Georges, the son of a prosperous planter from Guadeloupe and his African slave — was performed by graduate students in Harvard’s Music Department.

During the hourlong discussion last week at Harvard Art Museums, Gates encouraged listeners to explore Harvard’s vast annals for other stories.

The number of ideas “sitting in mute form in the archives” is endless, he said.

Wheatley secured her freedom after her book was published, but in the years that followed she struggled in poverty and interest in her work waned. She was unable to find a publisher for her second volume of poems and died at the age of 30.

But today, on the fifth floor of Harvard Art Museums, her voice rings clear.

“No More, America” is on view at the Lightbox Gallery through the end of the year.