A glass window frames The Harvard Museums of Science & Culture (HMSC) exhibit, “Scale: A Matter of Perspective,” examines the concept of scale and its power to transform perceptions of the world and our place in it, inviting visitors to make connections to the world in surprising new ways.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

‘Scale’ tells the story of how, and what, we measure

Museum exhibit explores how perspective changes understanding

Summing up one of life’s greatest mysteries in one word seems impossible. But with “Scale: A Matter of Perspective,” the Harvard Museums of Science & Culture does just that.

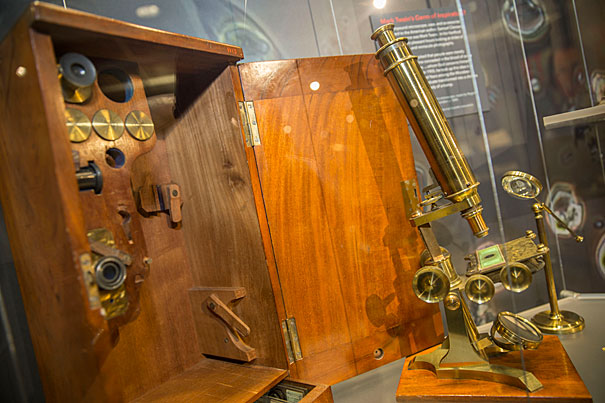

From the smallest visible speck to a Cepheid star in a faraway galaxy, the universe and everything in it is based on scales of all magnitudes, shapes and sizes, whether seen or unseen, known or unexplored, according to Sara Schechner, David P. Wheatland Curator at the Harvard University Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments. “Scale,” on view at the collection’s Special Exhibition Gallery, uses an assortment of rare artifacts to make this intangible concept corporeal.

“The kernel of this exhibit originally was to show how apparatus like the microscope and telescope changed the perception of the universe as teeming with things and life at all levels,” said Schechner, who helped curate the show. “But as the planning unfolded, it expanded into looking scale in a much broader way.”

A curatorial team from Harvard’s museums, libraries, and faculty united to create an exhibit that spans disciplines, examining scale as reflected by changing world views over time. It gives visitors a panoramic view of scale’s role in everyday life — from the clothes we wear and products we use to signs and symbols, sights and sounds, even social hierarchy and economy. It uses a cross-section of objects and ideas to explore scale from every possible angle, juxtaposing objects and settings to tell different stories or reveal historical context.

“The notion of scale depends on where we stand in history,” said Jane Pickering, executive director of the Harvard Museums of Science & Culture. “Bringing together the strengths of all the museums’ vast collections in an interdisciplinary way and developing this exhibition through a team approach enriches our exploration.”

At the center of the exhibit is a Maliseet chief’s coat from the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Made in the late 1800s of black wool, the frock-style coat is embellished with tartan cotton ribbon and European glass beads. Schechner said the piece embodies a narrative of indigenous social hierarchy, global commerce, and borrowing across boundaries.

A prominently displayed 125-year-old Bruce photographic telescope and astronomical glass plates from the plate stacks at Harvard College Observatory examine the vast realm of space exploration. Nearly invisible but significant details on the plates are magnified by the instruments and recorded in the log books of Henrietta Leavitt, an observatory employee whose work in the early 1900s annotating the plates altered the scale of the universe. Her findings eventually became known as Leavitt’s Law.

“Both literally and symbolically through time, things were scaled up or down depending on everything from the sizes of instruments and materials used to the hierarchies in social scales and changing world views,” said Schechner. “How is it appropriated, is it sized to be grand or diminutive, it’s all a story about scale.”

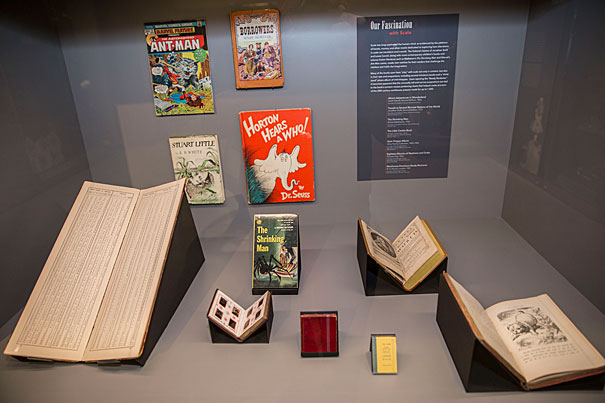

The exhibit playfully uses Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” as a recurring figure. Drawings of his heroine and quotes from the book help illustrate concepts like big and small, in and out, and the surprising approach the curatorial team took seriously.

“It was probably one of the most challenging shows we have ever done and we really had so much fun with it,” said Janis Sacco, director of exhibitions. “How do you make this eclectic group of objects fit together?”

The exhibit also features many actual scales and other scientific instruments, including Mark Twain’s microscope slides and a tiny telescope belonging to King George III. Proportion is addressed in a display of miniature books arrayed against the “Workhouse Provisions Ready Reckoner,” an exceptionally tall volume donated by the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. “Workhouse,” which includes a recipe for gruel, illustrates scale both in its form and format, giving recipes for one or 1,000.

Other artifacts capture differences in size and time scales simultaneously. The Harvard University Museum of Comparative Zoology’s Eryops megacephalus is a fossilized skull of a giant 300-million-year-old amphibian, displayed next to a small diorama showing its excavation. Nearby, one of the famous Blaschka glass plants from the Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries models the intricate structure of the slender rosette grass, which cannot be seen by the naked eye.

“It is rare for people to actually think about how when we change scale it can completely transform what we see,” said Sacco. “Once you’ve gone past what your senses can normally detect into worlds beyond everyday human experience, sometimes it’s profound enough that it changes you, and sticks with you forever.”

Scott Chimileski, a research fellow at Harvard Medical School’s Kolter Lab and a biologist on the “Scale” team, said in some ways scale is an illusion because it is all relevant to the observer.

“There is a microbial world hidden beyond our sight in any direction we look and in that world, all of the colors and shapes that we can imagine,” he said. “The scale of the world as we know it seems like a constant, yet it has changed drastically in parallel with modern science.”

Chimileski created photographic murals for “Scale” that show both the microscopic and cosmic, such as a scanning electron micrograph detailing natural chalk formations composed of trillions of tiny fossilized phytoplankton from the Cretaceous period. Massive blooms of this same type of phytoplankton, called coccolithophores, still live in the ocean today and can even be seen from space, Chimileski said.

“At Harvard, anything you can think of, any story you want to tell, any argument you want to make in an exhibition, you can do it,” said Pickering. “The material is here and that’s really important and something we care a great deal about.”

“Scale: A Matter of Perspective” is free and open to the public through Dec. 9 at The Special Exhibitions Gallery, Science Center 251, Sunday–Friday, 11 a.m.–4 p.m. A free public lecture and reception, “Knocking on Heaven’s Door: Scaling the Universe,” with Lisa Randall, the Frank B. Baird Jr., Professor of Science, will be held in Lecture Hall D of the Science Center on April 26 at 6 p.m.