Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony has found new life in the digital age, the subject of a work in progress by Alex Rehding, Fanny Peabody Professor of Music, which examines the deeper analyses and unique reinterpretations enabled by modern technology.

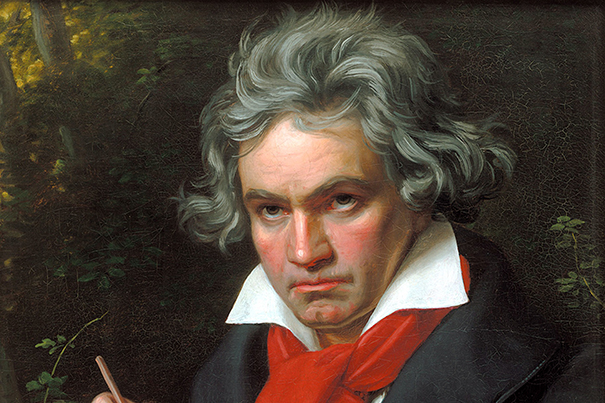

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Forever bringing joy

Book project on Beethoven’s Ninth has been an ear opener for professor

When Oxford University Press first asked Alex Rehding to write about one of the most iconic compositions in the history of music, the Harvard scholar wondered what he could possibly say that hadn’t been said before.

“Part of the challenge with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is that it’s the most written-about piece in the Western musical canon,” said Rehding on a recent morning in his Paine Hall office. “My first question was: ‘Do we really need another book on the Ninth?’”

His final answer: Yes, we do.

In time, the Fanny Peabody Professor of Music realized there was plenty new to say about Beethoven’s last complete symphony in four movements, which includes the stirring chorale finale “Ode to Joy.” And so he signed on to write a book about the Ninth as part of a series on canonical scores.

“In the last 20 years, there have been so many new things happening with it,” said Rehding.

Those new things range from flash mobs to protest movements to super-slowed-down versions of the piece. Completed after the German composer had gone deaf, the Ninth premiered in Vienna in 1824 to thunderous applause and has since delighted and inspired generations of music lovers. In 1985, “Ode to Joy” became the official anthem of the European Union.

Contemporary recordings and performances not only introduce the piece to new generations in interesting, often unconventional ways, said Rehding, they also transform how listeners engage with the work.

“On the one hand it is this old warhorse that everybody knows instantly,” he said. “On the other hand it continues to be really inspiring to so many people.”

Through the years many have taken the stirring message of brotherhood in “Ode to Joy,” written by German poet and playwright Friedrich Schiller, from the concert hall to the streets. In the 1980s marchers protesting the brutal regime of Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet sang it outside prisons, said Rehding, to let those behind bars know “they were not forgotten.” Similarly, student protesters calling for democracy in China’s Tiananmen Square in 1989 blasted the Ninth on improvised loudspeakers as a symbol of both hope and resistance.

Rehding is also fascinated by the way technology has helped transform the symphony for millions by giving it new life both on- and offline. He cited a YouTube video of a Spanish flash mob performance from 2012, an abridged version of the Ninth sponsored by a Catalan bank. The video begins with one tuxedoed bassist and ends with a public square filled with more than 100 professional musicians and singers entertaining a surprised crowd. It has drawn more than 70 million views, thanks in part to the notice of late author and neurologist Oliver Sacks, who included a link to the five minute and 41 second performance in his last tweet before his death.

“A beautiful way to perform one of the world’s great musical treasures,” Sacks wrote.

Rehding attributed the video’s popularity to the way the musicians deconstruct the complex shape of the movement, as well as our ever-shrinking attention spans.

“The form of the last movement is very, very complicated. We have 200 years of attempts to make sense of it. There is no consensus. But in the YouTube version they turn it into a simple strophic form like a song. I think that also tells us something about our contemporary listening habits. It’s six minutes long; that seems to be about the maximum length in our distracted age.”

Still, patient listeners will be rewarded by close attention to Leif Inge’s version of the Ninth, said Rehding. In 2002 the Norwegian conceptual artist ran the piece through an algorithm that “stretched out the digital code of a CD recording to make the sounds last 24 hours.”

While all the original pitches, harmonies, and rhythms are still there, they are played “unbelievably slowly,” said Rehding, making the piece unrecognizable. And what the careful listener will hear is a series of “grating dissonances.”

Those tiny musical clashes are present when even the most accomplished players are changing chords, but are hidden in real time.

“When you stretch out that time, these minute imprecisions suddenly become really audible and that’s the thing that you listen for,” said Rehding. “It’s really cool.”

In its day Beethoven’s piece was something of an outlier, starting with what Morton B. Knafel Professor of Music Thomas Kelly once described as “cosmic background sound,” and breaking with tradition by incorporating voices into a symphonic work. But its enduring appeal is clear, said Jeremy Eichler, classical music critic for The Boston Globe, who is devoting his Radcliffe fellowship to two books on music and cultural memory.

“It may seem remarkable that this massive acoustic orchestral work from the 19th century retains such charisma in the age of the earbud,” said Eichler, who hears the Ninth at least once a year, as part of the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s season-ending offering at Tanglewood.

“But I’ve never been to a performance that doesn’t touch this collective nerve and uncork a visceral response in the audience,” he added. “At this point it’s impossible to say how much that’s a reaction to the music itself, or to the sense of symbolic meaning it’s accrued over time — the score’s uncanny way of drawing out people’s optimism and sense of hope for the world. But without a doubt, the piece electrifies the audience year after year after year.”