Harvard Divinity School student Nestor Pimienta, founder of Tutoring Tomorrow Today, has won a HDS community service award and was selected to be part of Harvard’s Innovation Lab.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Taking care of their own

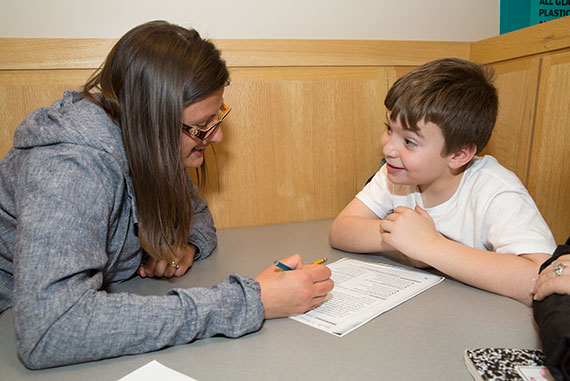

Tutoring program bolsters ties among Harvard students, workers, families

As an undergraduate in Los Angeles, Nestor Pimienta was often asked by university workers if he could tutor their children to steer them toward the road he took. Driven by a passion for social justice that he attributes to having grown up in an immigrant, working-class family, Pimienta ended up tutoring the son of a cafeteria worker, but he realized he could do more if others would join his efforts.

So he launched Tutoring Tomorrow Today, a program for college students to teach children of campus workers, and in the process build stronger bonds among students, workers, and their families.

“It’s an enriching experience for all,” said Pimienta. “It’s a community-building project in which students, workers, and their children learn from each other.”

At Harvard Divinity School (HDS), where he’s pursuing a master’s of divinity, Pimienta has refined his idea. After tinkering with the project at Harvard Innovation Labs’ Venture Incubation Program, he relaunched it in the spring of 2015, and was awarded the HDS SPARK Social Justice Award.

The program has had two runs and drawn 35 people among students, dining and facility maintenance workers, and their children. It stands out from the myriad programs in which Harvard students tutor disadvantaged children because workers take part in it. Cognizant that workers and students often interact on campus without really getting to know each other, Pimienta added a community-building meal as part of the program. After each tutoring session, workers, students, and children get together to share a meal and exchange personal stories.

That’s when the real lessons begin, Pimienta said.

“When people are eating together, a different kind of learning happens,” he said. “Both students and workers learn about each other’s lives. We’re breaking barriers by breaking bread.”

On a recent afternoon, a tutor brought challah, the traditional Jewish braided bread eaten on Fridays, to be shared by all. On other occasions, they have had pupusas, a Salvadoran flatbread, or Mexican burritos, or empanadas, Latin American stuffed bread.

“Workers love talking to the students,” said Pimienta. “And students love the chance to get to know workers. And for the children, it’s an opportunity to visit their parents’ workplace. Some had never been here before.”

High school sophomore Sydney Ramos is the daughter of Blanca Hurtado, a Salvadoran immigrant who has worked as a custodian at Harvard for the past 25 years. Ramos first set foot on campus for the spring’s opening session in April. Her visits to Harvard have given her a glimpse into what college would be like, and the meetings with her tutor have helped her focus on what she needs to start the road to college.

“My mom wants me to have a big future,” said Ramos, who attends Revere High School. “And I want to make her happy.”

Ramos’ mother is grateful for the chance to help her connect with a bigger community. “It made me feel that we aren’t abandoned,” she said, “that someone was looking after us.”

The work is also rewarding for tutors. Gabriella Chavez, an HDS student who grew up in California, said her work with Ramos has reinforced her desire to help Central American immigrants. Chavez’s mother hails from El Salvador. She hopes to be a resource for Ramos.

“We talked about college applications, but also about quinceañeras,” a Latino celebration of a girl’s 15th birthday, said Chavez. “The best part of this is that students, workers, and their children come together.”

Students and workers must apply to take part in the program. There are no major requirements, but those who want to be tutors undergo background checks and have to be willing to spend at least two hours a week for tutoring and sharing meals.

Aaron Duckett, who works at Cronkite Dining Hall, had met Pimienta at the cafeteria, and he and his 5-year-old daughter, Maggie, have been with the program from the start.

“She has grown leaps and bounds,” he said of his daughter. “She’s now ready to go to kindergarten.”

Though the program is small and known largely through word of mouth, Pimienta hopes that in the near future his project could expand to other colleges, nonprofits, and other organizations. After graduation, he plans to find work where he can “bring together different types of people for something meaningful,” or develop his tutoring program into a nonprofit.

“This is a good way of building community,” he said. “Students learn so much from the program, and the workers, and their families, feel part of the Harvard community. We’re showing that everyone has value and that we can learn from each other.”