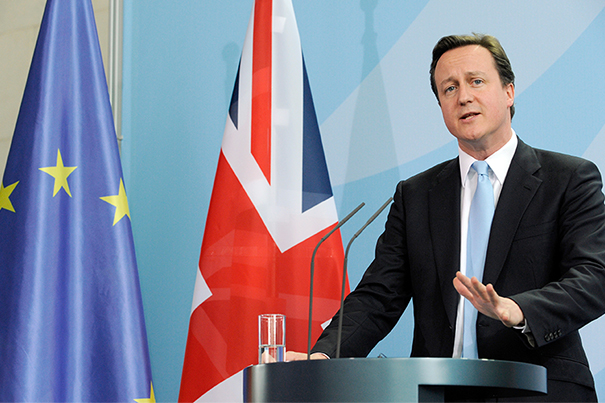

British Prime Minister David Cameron is at the forefront of a debate that has led to this month’s referendum on whether the United Kingdom should retain its membership in the European Union.

File photo by Rainer Jensen/AP

Britain muses: Play bridge or solitaire?

U.K. may vote shortly to quit European Union, with cascading economic and political effects

Yea or nay? What began as a political gambit by Britain’s Prime Minister David Cameron to secure victory for the Conservative Party in the 2015 general election has turned into a deeply divisive and existential question that has far-reaching implications for the future of the United Kingdom (U.K.) and the European Union (E.U.).

On Thursday, voters in the U.K. will decide by a simple majority whether to remain in the E.U. during a national referendum known as “Brexit” (a portmanteau of the words British and exit). Over the last month, public opinion polling showed voters evenly split, with the “leave” campaign edging up slightly in recent days.

“Leave” supporters, led by the nationalist U.K. Independence Party, include about half of the Conservative members of Parliament (MPs), some Labour MPs, and the Democratic Unionist Party. They argue that the U.K. loses more financially than it gains from E.U. membership and that withdrawing would protect Britain from the “uncontrolled” flow of usually low-skilled migrants from other nations who are looking for work.

“Remain” proponents include Cameron, most of the Labour Party, major British and global financial institutions such as the Bank of England and the International Monetary Fund, world leaders such as President Obama, and many E.U. nations, including France and Germany. They warn that the U.K. will suffer diminished political standing and influence and bear painful economic costs if it leaves, such as a loss of foreign investment that would permanently reduce its gross domestic product, an overall decline in trade with the E.U. as new difficulties or barriers are erected with the U.K.’s largest trading partner, significant job losses from international corporations, and rising national security costs.

Douglas Alexander is a senior fellow in The Future of Diplomacy Project at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. From 2011-2015, he served as the U.K.’s shadow secretary of state for foreign and Commonwealth affairs and held several ministerial posts between 2001 and 2010, including minister for Europe. The Gazette spoke with Alexander about the upcoming referendum and the potential fallout for the U.K. and Europe.

GAZETTE: What are the historical roots of the U.K.-Europe relationship debate?

ALEXANDER: The prime minister committed the Conservative Party to hold a referendum if it became the government back in January 2013. He did so under external electoral pressure from the U.K. Independence Party and internal political pressure from his own back benchers. Europe is an issue that has divided the British Conservative Party for decades, with a growing “Eurosceptic” wing within the Conservative Party who have sought the opportunity to remove Britain from the European Union. Britain last had a referendum back in 1975, and in the decades since that vote there has been a growing sentiment within the Conservative Party that Britain should leave the European Union. Today, with just days to go, we see the spectacle on British televisions and in British newspapers of Conservative cabinet ministers arguing against each other about the merits or demerits of Britain’s place within the European Union.

GAZETTE: Given that Prime Minister Cameron strongly favors remaining in the E.U., was it a mistake for him to have promised this vote?

ALEXANDER: I think the prime minister committed to this referendum out of weakness rather than out of strength. It was a tactic for trying to manage an increasingly unmanageable Conservative Party. But what started as a management strategy for a party has turned into a profound choice for the country. The consequences for a British exit from the European Union would be immediate and serious for the prime minister, but, much more importantly, they would be immediate and serious for the United Kingdom. We are at a time in European history where barbed wire fences are going up across Europe. The idea, as [President] George Herbert Walker Bush put it [in 1989], of “a Europe whole and free” and “at peace with itself” is being challenged in a manner we haven’t seen for decades. I personally believe that for Britain to leave the European Union would be the wrong choice for the United Kingdom, and while the choice is for people in Britain [to make], the consequences would be felt not just in Europe, but more broadly by the West.

GAZETTE: What are some of the likely political, economic, and national security consequences of leaving the E.U., and also who benefits by leaving and who will be hurt?

ALEXANDER: There isn’t a single and serious ally of the United Kingdom who is arguing that it is in their national interest that Britain leave. Some speculate that the only global leader who would welcome a British exit from the European Union is [Russia’s] Vladimir Putin. This would see Europe divided and weakened at a time when unity and resolve are required in the face of simultaneous security, migration, and economic challenges confronting Europe. So I believe that a choice for Britain to leave Europe would not only be damaging to Britain, but it would be damaging to Europe. A European Union without Britain would be smaller, poorer, and less influential on the world stage. And it has been the keystone of American foreign policy since the Second World War to see trans-Atlantic security as being supported both by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and by the European Union. That’s why not just President Obama, but Hillary Clinton, [Sen.] John McCain, and so many other Americans have spoken clearly and unequivocally that they judge the interests of the United States and the broader interests of the West would be served by Britain continuing to be a leading member of the European Union.

One effect of Britain leaving the European Union would be to see a strengthening of the populist, nationalist, and protectionist forces that are on the rise in Europe today. Marine Le Pen of the National Front in France has said she would welcome a British vote to leave the European Union, and there is no doubt that Britain leaving would lead to a significant shift in the balance of power in the E.U. from the liberalizing north toward a more protectionist south. A decision to leave would embolden parties like the National Front, the Law and Justice Party in Poland, and Jobbik in Hungary, who hope for a British exit as a defeat for the idea of Europe and the collective strength and solidarity that Europe represents.

Economically, there would be profound uncertainty for a sustained period about the nature of Britain’s economic and trading relationships, not just with Europe, but also with the rest of the world in the aftermath of a vote to leave. So I am strongly of the view that not just Britain but the interests of Europe and of the West more broadly would be served by Britain continuing to take a leading role within the European Union, alongside NATO, the United Nations Security Council, and the U.K. Commonwealth.

GAZETTE: Brexit proponents argue that the U.K. contributes far more financially to the E.U. than it receives in benefits, that regulatory red tape unfairly constrains business, and that migration has become an unsustainable economic and cultural drain on the U.K. What do you make of these arguments? And are the sovereignty and migration issues legitimate or just a pretext or dog whistle to try to animate voters to their side?

ALEXANDER: In the closing days of this campaign, we’re seeing a classic battle between the “remain” side, arguing about the economic costs and consequences of Britain leaving Europe, and the “exit” argument that the 23rd of June polling day is an opportunity to take back control. There is no doubt that the “exit” side is seeking to animate some of the same forces that we’re witnessing in U.S. politics today: a sense of economic anger, a sense of cultural anxiety, and a sense of political alienation. They are seeking to characterize this as a contest between the people and the government, between the elites and the people. That claim is strongly disputed by the “remain side,” who argue that the economic cost of exit will be borne most heavily by working people in Britain. One of the effects of the recent weeks of campaigning in Britain has been what some call the advent of “post-fact politics.” There’s an increasing unwillingness to agree on the facts and to diverge on the opinions, and that’s a source of real concern for many of us who are observing the conduct of this campaign.

GAZETTE: There’s worry that other dissatisfied nations like the Netherlands, Denmark, and Sweden might be inspired to leave the E.U. if the referendum succeeds. What’s your view? Would others leave, and could there be backlash against the U.K. by the E.U.?

ALEXANDER: In other European capitals, there is a very real fear of a contagion effect following a British decision to leave the European Union. One of the consequences would be that in the subsequent negotiations between Britain, the European Union, other European countries and governments will feel obliged to drive a very hard bargain so as to discourage other countries from thinking they can enjoy all of the benefits of membership in the single market without any of the responsibilities of contributing to the European Union.

If you’re a European leader today, you’re not only concerned about the possibility of a British exit from Europe, you have very real and continuing concerns about the refugee crisis on Europe’s southern border, about revolutionist Russia to Europe’s east, and the continuing economic challenges being faced by the Eurozone. So many European leaders would feel a deep sense of relief if British voters choose to stay part of the EU and will be concerned as to the broader impact on Europe if Britain chooses to leave.

GAZETTE: How seriously is this question being taken by voters? And given that polling appears to show both sides even or slightly in favor of the “leave” campaign, what do you think will happen, and why?

ALEXANDER: My sense is that there will be a reasonably high turnout in this referendum, although I would be surprised if it reached the level of the Scottish referendum on independence back in September 2014 when the turnout reached 84.6 percent, the highest recorded turnout since universal suffrage was introduced in Britain. My sense is the higher the turnout, the better for the “remain” side because the “exit” side is relying on its voters being more animated and more passionate than “remain” voters. So there will be a huge effort by both sides of this referendum campaign in the coming days to mobilize nascent support into active support on the 23rd of June.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.