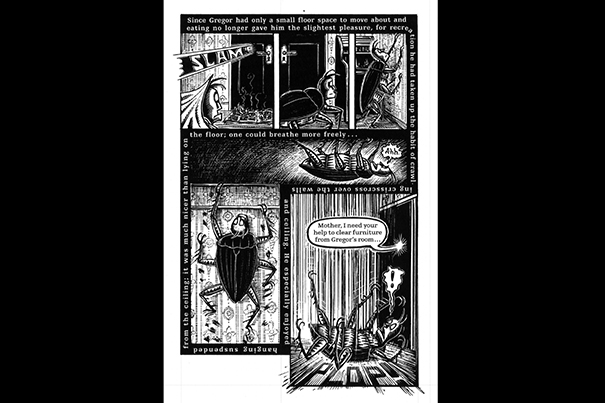

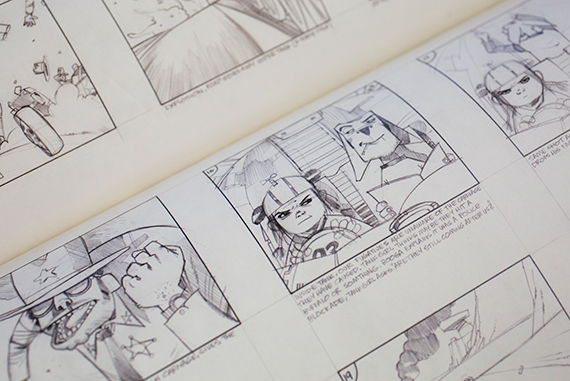

A page from Peter Kuper’s 2003 graphic adaptation of Franz Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis.” Kuper said Kafka’s writing allowed him to “really demonstrate ways of storytelling that only could be done in comics.” The text on this page, said Kuper, corresponds with the visuals that follow Gregor Samsa as he climbs the walls in cockroach form.

Artwork courtesy of Peter Kuper

Comic genius

Talk to focus on art form and its place in academic collections

For generations, comics, cartoons, and graphic novels have fueled imaginations with their superheroes from far-off galaxies, helped shape political discourse with their biting critiques, and made readers laugh and cry with their poignant reflections on the human condition.

Harvard’s own comic collection is vast and varied and includes wordless woodcut picture stories from the early 20th century, popular strips from D.C. and Marvel, and “The Walking Dead,” the black-and-white series that spawned the megahit TV show.

The range of the evocative art form will be front and center during a conversation titled “Visual Storytelling: Comics in the Collections” from 9:30 to 11:30 a.m. Wednesday at the Sperry Room at Harvard Divinity School’s Andover Hall.

The talk, part of the “Strategic Conversations at Harvard Library” series, will also explore the challenges of collecting and curating comics in an academic setting. Featured speakers are Peter Kuper, a cartoonist, illustrator, and visiting lecturer in the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies, and Jenny Robb, curator of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum at Ohio State University.

In an interview with the Gazette, Kuper, a regular contributor to Time, Newsweek, The New York Times, and Mad magazine, talked about the art, ambition, and importance of comics, along with his recent adaptation of Kafka’s “Metamorphosis,” a project whose original art and ancillary material Houghton Library has acquired with plans to make available for study.

GAZETTE: What would you say to those who might think comic books shouldn’t be considered part of a serious university collection?

KUPER: These people are mistaken, or simply uninformed on what has taken place in this area of art and literature. I’d like to think there are few people left who maintain this perspective (but as a cartoonist I’ve learned to live with disappointment). The answer is to point them in the direction of the incredible body of work that has been done. Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” is a natural starting point, but there is so much more that has been done since he won a Pulitzer for that book in 1992: Marjane Satrapi’s “Persepolis” (which was also adapted into an Oscar-nominated animated film), Alison Bechdel’s “Fun Home” (which has been adapted into a hit Broadway play), Joe Sacco’s “Footnotes in Gaza,” to name only a few. I’ll be bringing a recommended reading list to my Harvard talk.

GAZETTE: What are some of the challenges and barriers faced by those collecting and curating comics in academic settings?

KUPER: Cataloging so readers are able to locate the works requires that they are placed in subcategories and not all lumped under the “graphic novel” umbrella. Kafka adaptations should be with other Kafka books — not in humor or jammed in with every other graphic novel, as has been the case with many bookstores and libraries in the past. This may occasionally require buying more than one copy (hint, hint).

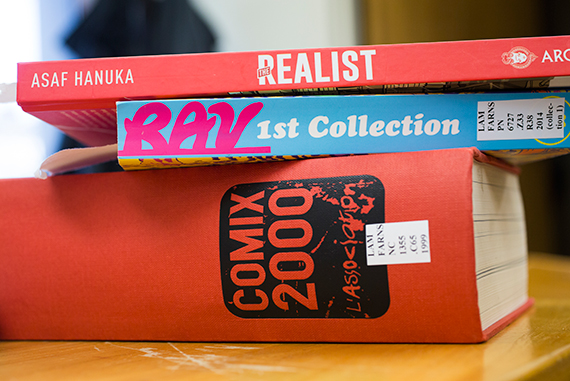

Comics collections at Harvard

Harvard’s collection of comics is vast and varied. It includes the autobiographical comic “The Realist” by Israeli illustrator and comic book artist Asaf Hanuka, published by Archaia (2015); the action-adventure drone comic “RAV” by Mickey Zacchilli, published by Youth in Decline (2014); and “Comix 2000” by various artists, published by L’Association (1999). Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

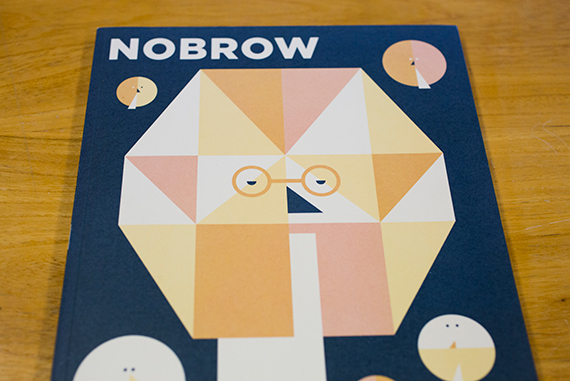

A collection of art comics and illustrations from the British independent publishing company Nobrow is part of Harvard’s comics holdings. The image above is from the cover of Nobrow #9, published by Nobrow Press (2014).

Harvard’s Lamont Library collections contain a number of comics and graphic novels, including popular items from DC and Marvel Comics. The page above, from “Batgirl/Robin Year One,” was published by DC Comics in 2013.

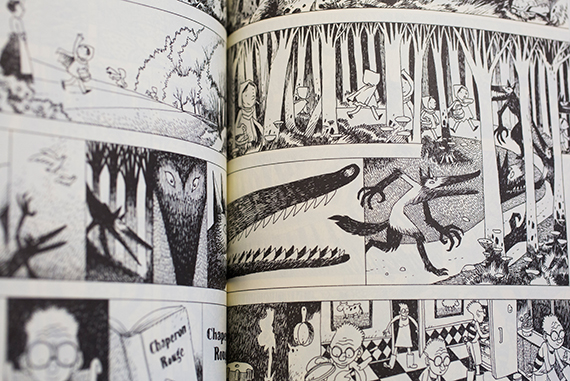

If a picture is worth a thousand words, one of Harvard’s comics holdings can speak volumes. The collection “Comix 2000” consists entirely of drawings without text, including this image from an untitled piece by artist Sergio Garcia.

The eponymous heroine of the British comic “Tank Girl” drives and lives in a tank, and dates a mutant kangaroo named Booga. This page is from “The Cream of Tank Girl” by Jamie Hewlett and Alan Martin, published by Titan Books (2008).

GAZETTE: Is there a distinction to be made between comics and graphic novels?

KUPER: If there’s a clear distinction (which there really isn’t), it would only be between comic book “floppies,” which are what superhero comic book magazines tend to be, and something packaged in a book format. This line has been intentionally blurred since the term “graphic novel” has gained greater respectability with book buyers, so it’s slapped on any comic that is done in a long form. Libraries have to be as discerning about graphic novels as they are about literature. There is genre material that is geared towards kids and young adults and other literary examples covering politics, autobiography, history, etc., that are aimed at adults. The biggest disservice is to treat comics as one form and isolate it all together.

GAZETTE: What is the role of comics and graphic novels in helping shape our culture? And what can they do that other media or art forms can’t?

KUPER: We are a very visually literate society and comics only encourage and increase that literacy. Unlike viewing a movie, which is a more passive act, comics create an intimate relationship between artist and audience that is very participatory. A comic requires that the reader make visual connections and follow a story from panel to panel, connecting the dots and deciding what takes place between panels. Comics are a unique language and can even function without words, telling a story through images alone. In this way, they can dismantle language barriers without sacrificing a complex story.

GAZETTE: As a political cartoonist, why do you think comics and graphic novels are such an effective tool for political and social commentary?

KUPER: One of the beauties of the form is the relationship between image and text. Comics allow the artist to show conflicting/ironic imagery to make a clear point. The caption can say, “They were overjoyed with the news,” while showing an image of crying people. It also can make information more accessible. In “Maus,” to have simple drawings of mice representing the Jews and cats representing Nazis allowed readers to engage with the subject and see themselves in the drawings. It was deceptively light in its visuals and gave readers a way to enter and understand the horrors of the Holocaust and its impact on the author and his subjects.

GAZETTE: What inspired you to adapt books such as Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis” and Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle” to graphic novels?

KUPER: With “The Jungle,” it was opportunity. A publisher was doing a line of “classics illustrated” and gave me a chance to do something longer form and in full color. This was at a time (1990) when bookstores and libraries were not carrying graphic novels. I saw this as a way to demonstrate the possibilities of the form with material that had been important to me growing up and hopefully break through to a non-comic-reading public. It had great limitations since I was adapting a 350-plus-page book into a 48-page graphic novel (the format the publisher had set), but it did reach a wider audience and began the process of opening doors to libraries and bookstores.

With “The Metamorphosis,” my adaptation was longer than Kafka’s story. I had previously adapted nine of his short stories in a collection called “Give it Up!” and loved the experience, so “The Metamorphosis” was a natural follow-up. Kafka’s writing acted as an anchor that allowed me to experiment with the art form and really demonstrate ways of storytelling that only could be done in comics. In one passage, in order to follow the text, the reader has to turn the book around 360 degrees, which is in conjunction with visuals following Gregor Samsa as he climbs the walls. I was also able to bring a style to the story that while reflecting German Expressionist art also had a comical quality that brought out the dark humor in Kafka’s writing.