Technical artist David Hopkins helped reconstruct the chair, which involved more than 2,000 individual pieces.

Courtesy of the Harvard Semitic Museum

Egyptian-style handiwork with a digital past

Artists draw on archive to re-create millennia-old ‘Queen’s Chair’ piece by piece

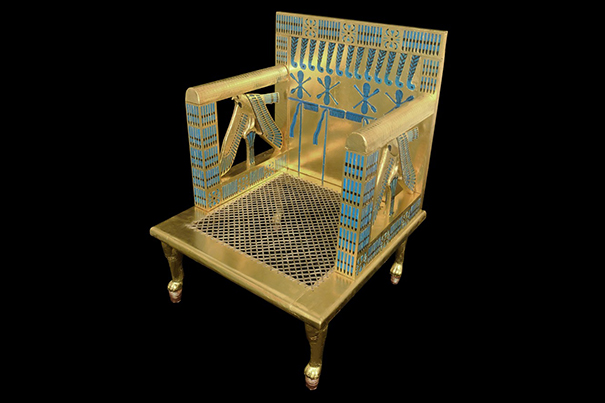

The chair is beautiful, its shiny gilding and bright-blue inlays catching the sun in the Semitic Museum’s stairwell landing.

A re-creation of a piece from a 4,500-year-old tomb, the chief value of this high-backed seat — a chair or throne for the Fourth Dynasty Queen Hetepheres — does not spring from its vaunted history, nor from the gold foil that was carefully glued onto the cedar, or even the brilliant turquoise faience, each feature individually crafted in molds of plaster and silica. Instead, its worth is in the roughly 1,000 hours spent putting it together, a process that not only proved the utility of a digital archive but also provided endless hands-on instruction in the way the ancient Egyptians most likely worked.

Queen Hetepheres’ tomb was discovered by accident in 1925. A joint Harvard University-Museum of Fine Arts expedition led by famed archaeologist George Reisner had been excavating the Eastern Cemetery (just east of the great pyramid of King Khufu) in Giza, Egypt, when a photographer’s tripod slipped, exposing the plaster cover of a hidden burial shaft. That shaft led the group down another 90 feet to a tomb, determined to be that of Hetepheres, Khufu’s mother.

After more than four millennia, the contents of the tomb — known as G 7000X — were in fragments. Organic components like wood and linen had rotted, and gold and ceramic had splintered. But Reisner and his crew were painstaking excavators, sifting carefully through the debris for two years. In addition to copious notes, they took more than 2,000 photographs, all with the idea of one day uncovering what had been in the tomb.

Over the ensuing years, several pieces from the tomb’s contents have been re-created for both the Cairo Museum and the MFA, including a carrying chair, a bed, a sitting box, and another, simpler chair.

This chair, however, never was.

“It was an amazing discovery,” said Peter Der Manuelian, the Philip J. King Professor of Egyptology and director of the Harvard Semitic Museum, who led the project. “But no one had attempted to reconstruct the second chair because it was so elaborate and fancy and people were just overwhelmed.”

The project became possible thanks to the ongoing digitization of the Giza site, which has made the extensive notes and photographs more easily searchable. “We have all this great 3-D modeling,” says Manuelian. “We’d scanned all the notes and drawings. Why not try to build this piece in the physical world? And, along the way, learn about Egyptian craftsmanship — and, even more, about the ancient manufacturing sequence, from carving the wood to doing the gilding and the faience inlays.”

Rus Gant, who as technical artist for the Giza Project is responsible for the overall conception and vision for the chair project, explained that the decision to re-create it served as “proof of concept,” showing what can be done “when you create an archive like this. How a digital archive can function in the modern world.”

Even with the digitization, the re-creation remained a daunting task, one that David Hopkins, the technical artist who did most of the computer work, carving, and final assembly, likened to assembling a jigsaw puzzle “when all the pieces have been tossed together with pieces from at least five other puzzles.” All in all, the reconstruction involved more than 2,000 individual pieces.

First, a small model was created — an almost dollhouse-sized replica that incorporated the 3-D digital imaging. This led to discussions of techniques, as well as materials. But although it would have been relatively simple to re-create the piece from those images, having a perfect replica was not the point.

“We were more interested in the actual archaeological process of how they did it,” said Gant. “How they crafted, rather than just recreating a chair.”

Using many of the same tools the Egyptians most likely used — chisels and lathes and sandpaper — the team made some discoveries. Joints in the furniture, for example, seemed to have been drilled at a 45-degree angle. This, the builders decided, probably allowed for a string of wet leather to be inserted. As the leather dried, it would shrink, binding the pieces tightly.

“As I’m digging this out,” Hopkins says. “I’d ask, ‘What did they use to dig this out with?’”

The process wasn’t completely replicated: Hopkins used a ShopBot milling machine to carve the chair’s wooden components. But the way pieces were designed and assembled were, as closely as possible, re-created, providing insight into the original craftsmanship.

When it came time to fit the faience ceramics, Kathy King, director of education at the Office for the Arts at Harvard Ceramics Program, had to reinvent techniques, using molds of plaster and silica that break apart after firing, leaving individualized faience pieces that fit pre-carved niches (a process in which she was assisted by ceramics associate Darrah Bowden). Christine Thomson, a conservator, worked on the gilding, with gold foil attached with gesso and animal glues to which the Egyptians would have had access.

The final re-creation of the chair.

Renderings by Rus Gant

Many mysteries still linger over the tomb. For example, where’s the body?

“Is it a ceremonial burial place for just the queen’s burial equipment?” said Manuelian. “Was she buried elsewhere and moved here? What happened to the body? We still have more work to do.”

Still, the Queen’s Chair, as it has been dubbed, has become a fount of information, some of it surprising. Gant pointed out that the seat, for example, is angled slightly — at the three degrees that craftsmen during the Bauhaus period would judge ergonometrically ideal. “They knew that 4,000 years before,” he said.

And the level of craftsmanship is no less impressive. “The mortise and tenon work is just as good as it was in the late 1800s,” said Hopkins. “Which is better than what we do now.”

Overall, said Manuelian, the project “gives us an angle into Egyptian craftsmanship. It brings alive for us just how elaborate and sophisticated this particular piece is. The end result is a teaching tool, a research tool, and a museum piece that now goes on display in the Harvard Semitic Museum.”