Treating addiction means treating a chronic disease, says Nalan Ward, director of MGH’s West End Clinic.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Working to break heroin’s grip

Specialists see promise in a more comprehensive approach to treatment, with key role for medication

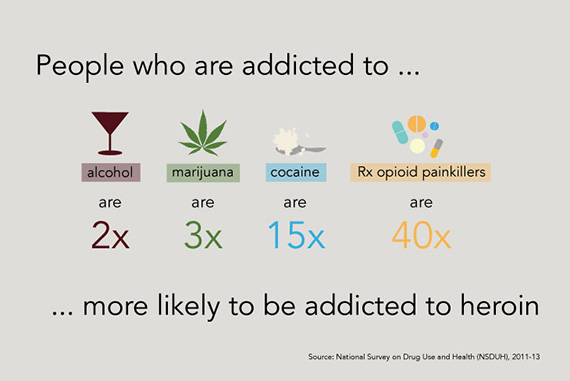

Death rates from heroin overdose nearly quadrupled in the United States between 2002 and 2013, when the number of people reporting past-year heroin abuse or dependence rose to 517,000, a nearly 150 percent increase from 2007. In 2014, the use of heroin and other opioids killed 1,256 people in Massachusetts, an increase of 34 percent over 2013 and 88 percent over 2012.

The Gazette sought insights across several disciplines for a three-part report on the crisis and new ideas for fighting it. Read the first part, on the science of addiction, here. Read the second part, on policy responses, here.

For many, Nalan Ward’s daily routine might seem unbearably depressing. As the director of Massachusetts General Hospital’s West End Clinic, an outpatient facility focused on drug-use disorders, Ward regularly treats patients caught up in a cycle of addiction.

Thirty-five percent of patients who walk through the doors of her clinic are suffering a primary opioid-use disorder. And 70 percent of those patients arrive with another serious medical condition directly related to or worsened by the drug use, such as hepatitis C, endocarditis (an inflammation of the inner layer of the heart), or sepsis.

Then there is a whole group of complications closely tied to addiction. Seventy to 85 percent of the clinic’s patients, Ward said, are depressed, anxious, or experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder. Such a range of symptoms often presents a confusing tangle of cause and effect, one that makes addiction particularly hard to treat.

“It’s a complicated, sick population with psychosocial needs complicated by unemployment, no stable place to live, legal issues … these are the kind of patients we see,” said Ward.

But for the Turkish-born doctor, the work is anything but depressing. Her attitude is “positive,” not “burned out and negative,” she says, and she finds nourishment in the knowledge that her efforts save lives.

It wasn’t always so. As a young psychiatric resident at Boston Medical Center, Ward became frustrated struggling to treat “hard-to-engage” patients who landed in the emergency room in the middle of the night suffering from withdrawal.

“It’s just a very bad setting to encounter patients with addictions. You are trying to rationalize or figure out what’s going with someone who is totally intoxicated. There is not a lot to offer in an acute-care setting. Those are some of the things that shape residents’ views and feelings about addiction, and they don’t necessarily see the good, see the long-term outcome.”

Ward is just one of many people in the Harvard medical community attacking the scourge of addiction as users of heroin and other opioids continue to fill emergency rooms, hospital beds, and treatment centers.

From 2011 to 2012 McLean Hospital saw a 10 percent jump in opioid-addicted patients in its detox unit, said Kevin Hill, director of the hospital’s Substance Abuse Consultation Service. The increase came despite a rise in the number of patients turned down for inpatient treatment by insurance companies that preferred outpatient options, he said.

Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital has accepted more than 200 patients at a treatment clinic that opened in 2013. More than half of the clinic’s 100 active patients have histories of heroin use. At Brigham and Women’s itself, in six years the rate of opioid-related inpatient consults for addiction has increased from 22 percent to 75 percent, said addiction psychiatrist Joji Suzuki, who works with patients at both hospitals.

Suzuki noted that the profile of opioid users has also changed. “Today they are younger, more educated, less likely to have HIV … patients come from all walks of life.”

What’s happening locally reflects what’s happening across the state. According to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the number of patients admitted to programs contracted by or licensed to the Bureau of Substance Abuse Services who listed heroin as their primary drug rose from 38.2 percent in 2005 to 53.1 percent in 2014.

‘The more I work with those who suffer, the more I am encouraged by how people change, their ability to change, and the ways we can help.’

Doctors, nurses, and counselors at Harvard-affiliated hospitals and institutes are determined to offer hope, providing inpatient and outpatient care and drug-assisted therapies. Research is regularly shining new light on the best treatment options. And addiction specialists across Harvard are working to integrate medical and psychiatric services, facilitating treatment in primary-care settings, addressing co-existing conditions, and ramping up access to effective medications.

There also has been a concerted effort to remove the stigma surrounding substance use. Addiction, experts agree, needs to be considered a chronic disease, not unlike asthma, diabetes, or high blood pressure, and managed the same way, with interventions such as medication and regular monitoring, and an understanding that relapse is often a routine part of recovery. The treatment standard needs to shift from an acute-care model, they argue, to one of long-term recovery management.

“We really have to embrace the idea,” said Ward, “that this is a chronic disease.”

Assessing the landscape

Addiction specialists agree that opioid-use disorders demand a multilayered approach, with medication, self-help, counseling, and family support all key to sustained recovery. It’s an addiction known to be particularly difficult to treat, with first-year relapse rates surpassing 80 percent, according to some estimates. Clinical trials have shown that medication-assisted therapies, often in combination with other treatments, offer opioid addicts some of the best chances at long-term recovery.

For years, two drugs have led the way in helping ease people off their dependence on opioids: methadone and buprenorphine. Both medications mimic the drugs they are meant to overcome by activating opiate receptors in the brain, yet their longer-acting formulas prevent the “high” of a drug such as heroin while helping reduce the cravings and withdrawal symptoms that can trigger relapse.

Approved for use by the Food and Drug Administration in 1972, methadone is still considered one of the most effective medications available for opioid addiction. To be eligible for methadone maintenance treatment a patient must have been suffering from opioid addiction for at least a year and must have failed at least one other type of intervention. The drug is strictly controlled: Patients must visit a federally regulated methadone clinic to receive their daily dose. For some, such a structured treatment works well. But for others the demands of the regimen rule it out, often in tandem with a sense of shame.

“Methadone is an incredibly effective treatment option, but there continues to be a lot of stigma around its use,” said Sarah Wakeman, medical director for the substance-use disorder initiative at Massachusetts General Hospital. “People call it the liquid handcuffs because you are sort of linked to the clinic. You have to be there every morning, no matter what, rain or sun. It’s hard to go on vacation, it’s hard to build your work schedule around it.”

In October 2002, the FDA radically changed the treatment landscape when it approved buprenorphine for opioid addiction. Instead of referring patients to a special clinic, certified doctors could prescribe the drug in their offices, enabling patients to take the medicine on their own. “It put addiction treatment back into the mainstream of medical practice,” said Roger Weiss, chief of McLean’s Division of Alcohol and Drug Abuse and director of the hospital’s alcohol and drug abuse research program.

Weiss is well-versed in the effectiveness of buprenorphine. In 2011 he released the findings of the largest study to date on treatment for prescription-opioid dependence. The findings demonstrated both the difficulty of beating an opioid addiction and the promise of buprenorphine.

In the study’s first phase, addicts used buprenorphine for four weeks, tapering off the drug, and then received no further medication. The pull of opioids was illustrated by the rate of patients — just 7 percent — who were subsequently successful at staying clean.

In the second phase, directed at the relapse population, subjects received 12 weeks of buprenorphine treatment, at the end of which 49 percent, seven times as many, were doing well. During the four-week taper from buprenorphine, half of those patients relapsed. There were more relapses — two-thirds of the remaining group — in the two months after the taper period ended.

“It showed the effectiveness, at least in a short-term treatment like this, of staying on medication,” Weiss said.

A follow-up study of the same patients showed that 3½ years later, many were coping better than they had in the short term, including those who received no medication and had high relapse rates.

“The course of this disorder is not constant,” Weiss said. “People have periods of recovery, then periods of relapse and, over time, a number of people do well, but not everybody. There’s a high relapse rate.”

Yet even with research supporting the efficacy of buprenorphine, patients across the country routinely struggle to get it. When the FDA sanctioned the drug 13 years ago, the hope was that doctors would begin prescribing it for appropriate patients in their practices. But few actually have. According to the nonprofit National Alliance of Advocates for Buprenorphine Treatment, only 3 percent of the 800,000 doctors in the United States are certified to prescribe it. In Massachusetts, just 751 doctors authorized to treat opioid addiction with buprenorphine are listed on the website of the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

“The drug companies are manufacturing it, the treatment exists,” said Wakeman, long a licensed prescriber. “There’s not a drug shortage, there’s a doctor shortage.”

One hurdle facing physicians is the added training required for certification. Doctors must take an eight-hour course, pass a test, and then register with the Drug Enforcement Agency, which grants prescription licenses. Doctors in their first year are allowed to treat a maximum of 30 patients and must reapply in order to increase their patient capacity to 100. Insurance is also a factor. Some providers require prior authorizations, set arbitrary dose limits, or even encourage doctors to stop prescribing buprenorphine altogether.

Even among the certified, the number of prescriptions for buprenorphine remains low, partly because many doctors simply aren’t comfortable treating addiction.

“They don’t feel they know enough about it, and they find it kind of a daunting task,” said Weiss, “and so they just say ‘Let somebody else do it.’ I think that’s really the issue.”

Ward agreed.

“People get trained to prescribe this medication. They hold a license for it but they don’t necessarily treat patients because they don’t feel comfortable.”

Another issue is the idea of total abstinence espoused by many 12-step programs and residential treatment facilities. It’s not unheard of for patients to resist medication regimens. Mark Albanese, the director of Adult Outpatient and Addictions Services at the Cambridge Health Alliance (CHA), said sometimes his patients complain that they feel as hooked on their prescriptions as they had been on heroin. To calm their fears, Albanese offers a little perspective.

“I say, ‘Let’s step back for a second. Tell me how much alike your life is now versus what it was when you were actively using heroin?’ And they just laugh at me and say, ‘It’s nothing like that.’”

Collaborative thinking

One model of care, in place at Brigham and Women’s for years, focuses on treating patients in non-specialized settings.

“We still need the specialty addiction clinics for patients who want it, who can access it, but here at the Brigham we focus on offering similar approaches without sending patients somewhere else,” said Suzuki. “We try our best to actually take ownership of it and say, ‘This is a major health issue that’s impacting your health and we’d like to help you.’”

When an opioid-addicted patient checks in at the Brigham seeking treatment for anything from a broken leg to pneumonia, a dedicated team, including an addiction physician, a group of addiction fellows, and a social worker, is activated. The group meets with the patient to discuss treatment options and to offer to immediately start him or her on buprenorphine.

“Beginning treatment while they are here in the hospital … while it seems like such a small thing, at many hospitals it’s simply not done,” said Suzuki, the team’s attending addiction psychiatrist.

Suzuki and his team help connect hospitalized patients with outpatient treatment options and community-support groups, enlist the aid of family and friends, and review relapse-prevention skills. Suzuki also works closely with the Brigham’s primary-care clinics, offering specialized guidance.

“We’re not trained; we don’t have any expertise; we don’t have any clinical support; we don’t have enough time; I am afraid of these patients … there’s a long list of barriers that people working in the clinics describe,” he said.

Undergraduate health coaches support the clinics. The students, often on a pre-med track, call patients to check on mood, cravings, and pain, as well as to monitor prescriptions and issue appointment reminders. They also relay any concerns they may have about the patient back to the team.

For doctors trying to manage their already-stretched time, the support model, said Suzuki, “has a potential of actually making a big difference on a wider scale.”

A similar approach is underway at MGH, which is building on early efforts to offer buprenorphine in its community health centers in 2003, soon after the drug received FDA approval.

Last year an updated strategic plan in which MGH re-examined its long-range clinical mission made targeting addiction a top priority. In the next three years the hospital will spend $3.5 million on long-term substance-use disorders.

The effort calls for collaborations among medical and psychiatric services to enhance addiction care, including a recently formed hospital-based Addiction Consult Team, similar to that at the Brigham. The team consists of psychiatrists, primary-care doctors, nurses, and social workers, and is called when a patient suffering from addiction is identified.

“This is a new formal consult service where folks are working together and bringing the best state-of-the-art treatment together for all types of substance-use disorders,” said James Morrill, chief of the Adult Medicine Unit at MGH’s Charlestown HealthCare Center.

The team helps connect hospital patients with outpatient services, in part through recovery coaches, ex-users affiliated with one of MGH’s three community health centers. The coaches also work directly in the centers, helping patients with everything from recovery support to how to find housing.

Focus on training

Improving access to treatment includes easing doctors’ interactions with patients fighting substance-abuse disorders. And that engagement has to happen as early as possible.

At Harvard Medical School, students first learn about addiction during an introductory psychiatry course in their second year. The class covers the epidemiology, public health impact, and neuroscience of addiction, as well as the range of treatment options and community support available. Students also learn how to interview and screen drug users. During clinical clerkships at Harvard-affiliated hospitals in their third year, HMS students engage directly with patients suffering from opioid addiction in a variety of settings.

But among teachers at HMS, which is currently overhauling its curriculum, there is a growing realization that perhaps the best way to help prepare students to treat addiction is to connect them with patients sooner.

“One way that the curriculum is moving as part of the HMS curricular reform is toward covering the really important parts of lots of important topics in a shorter period of time pre-clinically, and then getting students involved with patients from the get-go,” said Todd Griswold, a psychiatrist at the Cambridge Health Alliance and the director of medical student education in psychiatry at HMS.

Asked if addiction training could be increased for Harvard’s medical students, Griswold said “absolutely,” but with the caveat that so too could training in a range of other areas. “If you add to a particular topic, you have to think about what you are going to remove.”

When it comes to prescribing buprenorphine, more doctors and students need to learn how to do it, experts say. At MGH, Ward is making that happen. Together with a group of colleagues she has helped offer training in buprenorphine treatment to doctors across the hospital, positioning them to receive DEA approval. Last month she helped train primary-care residents during an annual retreat that for the first time focused on buprenorphine.

Wakeman is also working to sharpen residents’ training. As chief resident at MGH in 2012, she helped develop a survey of internal-medicine residents at the hospital that showed most felt unprepared to diagnose and treat patients suffering from substance-use disorders. In response, MGH boosted the number of lectures on addiction from one a year to 12. Progress was limited. When Wakeman repeated the survey with the new curriculum, the results showed that while residents were significantly more prepared, their knowledge hadn’t increased.

“That really gets to the fact that we learn medicine through doing and seeing,” she said.

For more hands-on training, internal-medicine residents are beginning to round with MGH’s Addiction Consult Team, and there is a push to have the intensive two-week outpatient rotation in addiction required for primary-care residents extended to all internal-medicine residents.

“We are in the middle of a public health crisis,” said Wakeman. “We have treatment that works and yet doctors aren’t providing that treatment, and I think the only way to really change that, change that culture, is to better train the next generation of doctors to feel like this is something that they own, that it’s a part of our skill set and that they have the tools they need.”

The other side

In contrast to those difficult nights in the ER, Ward these days can see further along her patients’ journeys, and can feel the hope they keep close. After years of working with people struggling to get clean, she understands just how incredibly complicated treatment is. She knows addiction is a disease that takes a vise-like hold on users with certain genetic susceptibilities, and that over time it can actually alter the way the brain functions, making “drug-free” seem excruciatingly distant. She also understands the treatment map and the range of effective therapies that can bring addicts back from the edge.

Still, even within the medical community, she acknowledges, there are doubters, those who wonder why she spends so much effort on patients who, to many, seem beyond help. They don’t bother her.

“It’s an opportunity to educate,” Ward said, “to say, ‘Look, there’s a whole different side to this disease and treatment is not that straightforward, but individuals who suffer from substance-use disorders can be treated.

“There is hope in this field,” she emphasized. “Addiction’s not a death sentence. It’s not your destiny. I think the more I work with those who suffer, the more I am encouraged by how people change, their ability to change, and the ways we can help. Every day, I am more and more impressed.”

Harvard staff writer Alvin Powell contributed to this report.