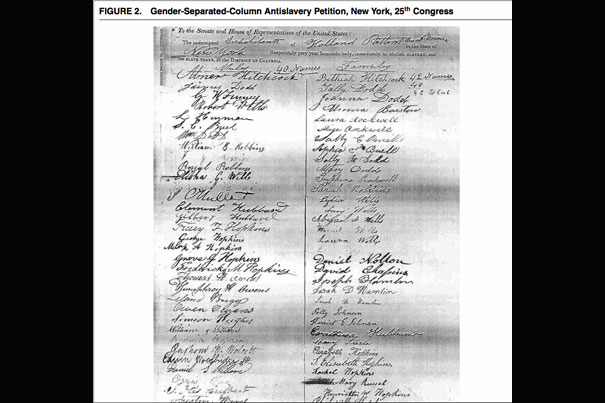

The gender-segregated signatures on this anti-slavery petition (image 1), sent to the 25th Congress from upstate New York, illustrate the “separate spheres” of household life in antebellum America. The work done by study co-author Daniel Carpenter (image 2), points to a trove of petitions now languishing in state and national archives. Another example (image 3) is a “Petition from Ladies of Marshfield, Massachusetts, 1835.”

Images (1, 3) courtesy of National Archives; file photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Foreshadowing feminism

Petitioning against a congressional gag rule on slavery before the Civil War spurred generations of activists

Decades before the Civil War, girls as young as 11 helped gather signatures on anti-slavery petitions sent on to a recalcitrant U.S. Congress. That simple act of canvassing became a crucible of activism that transformed the American political landscape, propelling generations of women into social causes after the war.

So argues a new paper co-written at Harvard. The “skills and contacts” that canvassing conferred on women who opposed slavery, wrote Harvard political scientist Daniel Carpenter in the American Political Science Review, “empowered their later activism.” In great numbers, he said, these former canvassers went on to use their new mastery of networking, persuasion, and organization in other movements, including campaigning for women’s right to vote.

Carpenter is the Allie S. Freed Professor of Government, director of Harvard’s Center for American Political Studies, and director of social sciences at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

He and co-author Colin D. Moore, Ph.D. ’09, a professor at the University of Hawaii, analyzed a new data set of more than 8,500 anti-slavery petitions sent to Congress between 1833 and 1845 — information that took eight years to gather, said Carpenter. The petitions themselves are not digitized, but the data set locating and characterizing them is the first “comprehensive statistical analysis” of such documents sent to Congress during the era of the infamous “gag rule” on the issue.

In 1835 the 25th Congress, under pressure from pro-slavery Southern Democrats, imposed restrictions on those petitions, which in those days were often called “prayers,” or pleas for redress of social ills. Petitions could still be sent to Congress, the rule said, but they would not be read on the floor, entered into the record, or referred to committee. That invalidated the time-honored steps, from the colonial era on, by which petitions often became the bases for new laws.

It was during this time that former President John Quincy Adams, then a congressman representing the Quincy-Braintree district of Massachusetts, would rise from his seat to offer an anti-slavery petition, only to be shouted down.

There is a century of scholarship looking at the gag rule itself, said Carpenter, but little on the petitions sent to Congress during that era, and no “complete description of them.” (Most such petitions called for mild, halfway reforms, and seldom an outright ban on slavery.)

But the gag rule, called the Pinckney Resolution 3, led to something quite different from its intent. Overnight, the number of anti-slavery petitions increased. And the gag rule awakened fervor among American women, said Carpenter.

Before 1836, women had been active in largely nonpolitical reform movements such as benevolence and temperance societies, he said. But now they feared that petitioning — their primary means of public political expression — was threatened. They ceased just signing petitions, and began writing them and mobilizing volunteer canvassers.

“Women’s canvassing exploded,” especially from 1837 to 1841, the study said. “The gag rule … cast women’s separation from the public sphere in stark relief.”

The effect was electric and permanent, said Carpenter. “It mobilized an entire generation of women,” he said. “It is quite clear that the gag rule was perceived as a spiritual and political affront.”

Female canvassers and their male counterparts stepped up the volume of anti-slavery petitions to Congress, said Carpenter. “Even though they knew these petitions were being tabled, thousands of them were flowing in.” He now sees the gag rule as a moment that changed the American political landscape by changing the role women played in it.

The flood of anti-slavery petitions suggests a puzzling question. “You petition the sovereign, which goes back to the Middle Ages,” said Carpenter. “But why do you spend more energy doing so when you know the sovereign has sworn to ignore them?”

The answer is that the “main audience” for anti-slavery petitions was not Congress, he said, but the press and the American public, the “townships, villages, rural hamlets across the United States where the state of anti-slavery opinion was still in play.”

At that time, women could not vote or own property, but as canvassers they quickly deployed the advantages already theirs: extensive social networks and powers of persuasion honed by arguing issues of moral reform. Women also made good canvassers, said Carpenter, because they were perceived as trustworthy — unsullied by partisan life, and therefore not subject to political corruption.

Add stamina, perhaps, to that list of women’s advantages. Many anti-slavery petitioners walked 20 miles or more a week in search of signatures. “It was a formative moment,” said Carpenter of the talk-filled strolls while canvassing. “Walking was both a sign of physical and spiritual and emotional commitment, and a pathway to their future activism.”

Stamina and other advantages paid off, the study said. Female activists gathered twice as many signatures as their male counterparts during canvassing, even though they circulated the same document in the same cities and towns. “The ability of women to sign petitions as women, en masse, and to take an organizational role,” said Carpenter, “really marks a huge break with the social and political structures of the time.”

The study also found that women were four times likelier than men to come to post-Civil War activism through prewar anti-slavery petitioning.

Anti-slavery petitions of that era, not surprisingly, reflected the gender divide of antebellum America. There were women-only petitions, emphasized in the Carpenter-Moore study, along with petitions in which the columns of signatures were segregated by gender.

“Women and men were regarded as having separate spheres,” said Carpenter, who in the paper acknowledged Harvard historian Nancy F. Cott’s contribution to the scholarship of 19th-century norms of gender segregation. She is the Jonathan Trumbull Professor of American History and the author of the landmark 1977 book “The Bonds of Womanhood: ‘Woman’s Sphere’ in New England, 1780-1835.”

The Carpenter-Moore study undercuts the myth that social activism among women was driven by those in the higher classes. Women and girls active in antebellum petitioning, they found, “came disproportionately from the middle and lower rungs of the socioeconomic ladder.”

One of the youngest known canvassers was Charlotte Woodward of western New York, who began gathering signatures at about age 11, apparently without the company of her mother. A few years later, in 1848, Woodward was living at home, making a few dollars at piecework by sewing gloves. But anti-slavery canvassing had primed her for activism. At 18, she became the youngest signer of the Seneca Falls Declaration, the primary document of civil rights for American women. Woodward was the only one of the original 68 Seneca Falls signatories to live to see women win the right to vote in 1920.

To get to Seneca Falls in 1848, Woodward remembered riding 40 miles in “a democrat wagon drawn by fat farm horses,” joining a long procession of women and girls and sympathetic men. She also resented her menial work in those days, unrewarded by regular wages: “I do not believe there was any community anywhere in which the souls of some women were not beating their wings in rebellion,” Woodward said later. “Every fiber of my being rebelled.”

Adding to the energy of the era, said Carpenter, was the Second Great Awakening, a revival-centered religious movement in which people turned to a communion with God that did not require the intercession of a church authority, a mindset that jibed with a time when petitioning for social reform reached an analogously energetic pitch. (Woodward herself lived in the “Burned-Over District,” a region of New York ablaze with revivals, including Seneca Falls.)

The Carpenter-Moore study reminds readers of other now-obscure figures. Lydia Carpenter of Boston was a teenager when she started as an anti-slavery canvasser. The study also reanimates forgotten Massachusetts activist Maria Weston Chapman, chief lieutenant to anti-slavery icon William Lloyd Garrison.

The study reminds readers of the equally forgotten Angelina and Sarah Grimke, a pair of South Carolina sisters who, as witnesses to slavery, went on to write and make public speeches on behalf of both racial and gender equality, sometimes as the stones from mobs outside rattled against the windows.

Women canvassers received transformational training in activism, the Carpenter-Moore study found. The study also reintroduced a hidden treasure to researchers investigating the origins of American political activity in the early 19th century: a trove of petitions now languishing in state and national archives.

In February, Carpenter and his colleagues will unveil a digitized set of petitions of all kinds sent to the Massachusetts Legislature between 1770 and 1870. Those petitions, are “much more strident” than those forwarded to Washington, D.C. “If you sent them to the U.S. Congress,” said Carpenter, “you took a more conservative tone.”

Beyond the Massachusetts petitions, and those of 1833 to 1845, there are untapped troves of petition records all over North America, he said, two centuries or more of formal pleas in English, French, Spanish, and Native American languages on social, economic, and religious issues. “We certainly don’t have anything resembling a full record,” said Carpenter.

So in the next few years he plans to research a wide-ranging book. “In the longer term, I’m interested in the history of petitioning in North America,” said Carpenter. “It’s not just a United States story.”