Jill Lepore’s latest book peels back the curtain on the history of the most famous female superhero Wonder Woman, created in 1941 by Harvard graduate William Moulton Marston.

Image courtesy of Alfred A. Knopf; photo by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

A sense of Wonder

Lepore’s history of superhero blends personal, political

In a nod to her latest subject, the historian Jill Lepore made it clear that she wasn’t about to back down from a fight for justice.

“If you want to doubt that Wonder Woman is a feminist project, we’ll have to take that outside,” the David Woods Kemper ’41 Professor of American History jokingly warned a Radcliffe audience on Thursday while discussing her new book, “The Secret History of Wonder Woman.”

As it turns out, explained Lepore, the superheroine’s backstory is not only firmly rooted in feminist ideals, it’s also firmly rooted at Harvard. The creator of the most popular female cartoon character in history was a Harvard graduate, William Moulton Marston, who earned his bachelor’s degree, law degree, and Ph.D. in psychology from Harvard, and whose personal life and beliefs, deeply influenced by 20th-century feminists, were often splashed across the pages of Wonder Woman comic books.

“Marston’s comic book,” said Lepore, “is actually autobiographical.”

The politics behind Wonder Woman

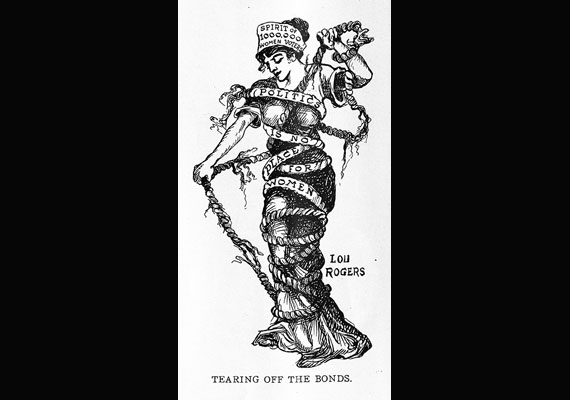

A 1912 drawing by the feminist cartoonist Annie Lucasta “Lou” Rogers, for the humor magazine Judge. Credit: University of Michigan Library

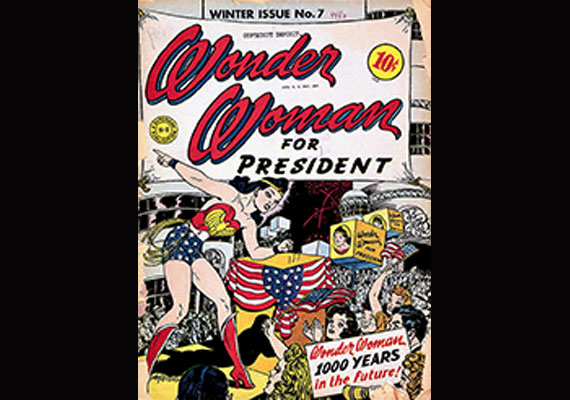

In the 1943 comic “Wonder Woman for President,” the superhero throws her hat in the ring for president of the United States. Credit: The Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington, D.C.

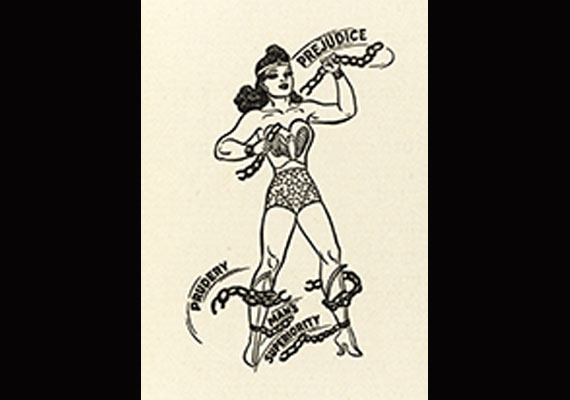

A drawing by Wonder Woman artist Harry G. Peter accompanied an article titled “Why 100,000,000 Americans Read Comics” by William Moulton Marston, which ran in “American Scholar” in 1944. Credit: Harvard College Library

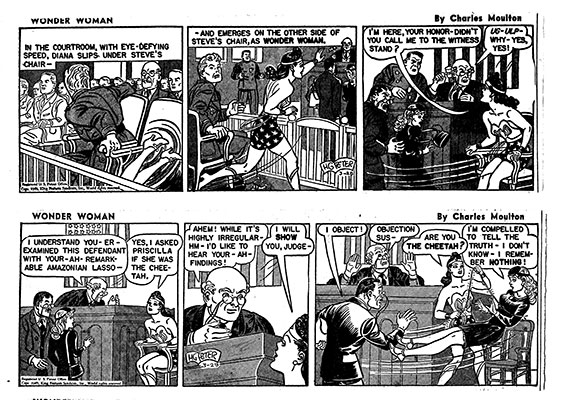

A 1945 newspaper Wonder Woman comic strip depicts the superhero using her lasso of truth on the witness stand. The comic’s creator, William Moulton Marston is credited with creating the lie detector test. Credit: The Library of American Comics

Wonder Woman first appeared in 1941. People and events from Marston’s life showed up regularly in the strip, including his efforts to use his lie-detector test, based on a person’s systolic blood pressure and developed and tested at Harvard, in court. Where Marston failed, Wonder Woman succeeded, using her magic lasso of truth on the witness stand on a woman suspected of leading a double life as the villain known as the Cheetah.

But the underlying theme in Marston’s work was Wonder Woman as equal. Time and again his storylines put Wonder Woman at the center of “boycotts, strikes, and political rallies,” Lepore writes, where demands included better wages and more opportunity in careers and higher education. In a 1943 episode, Wonder Woman ran for president of the United States.

“Marston’s Wonder Woman,” writes Lepore, “was a Progressive Era feminist, charged with fighting evil, intolerance, destruction, injustice, suffering and even sorrow, on behalf of democracy, freedom, justice, and equal rights for women.”

In another barely veiled nod to feminism, the only way Marston’s Amazonian princess, who disguised herself as secretary Diana Prince, could lose her powers was if a man tied her down, which many men did repeatedly in the 1940s and ’50s. But while many readers have viewed the bondage scenes as sexual, Lepore said she sees something else in the imagery.

“The bondage, gagging in Wonder Woman,” she told her listeners Thursday, “looks political to me.”

Marston’s dedication to feminism developed early. During his freshman year the famous suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst was denied access to campus to give a talk. She delivered it instead in a packed-to-capacity hall on Brattle Street. Men climbed the walls trying to get in.

After college Marston married Sadie Elizabeth Holloway, a dedicated feminist who received her master’s in psychology from Radcliffe while Marston studied around the corner where women weren’t allowed.

Wonder Woman’s promise, Lepore told the Radcliffe crowd, “is to teach boys and girls that women can do anything, that girls can grow up and do anything.”

Whether Marston actually lived his beliefs was a question complicated by his extremely complicated domestic life. Ten years into his marriage he delivered an ultimatum to his wife: let his new lover live with them, or he would leave her. The new lover was Olive Byrne, who also happened to be the niece of Margaret Sanger, the founder of the first birth-control clinic in the United States.

The three set up house in Rye, N.Y., where another occasional lover lived with them on and off in the place they christened Cherry Orchard. Byrne raised the children, hers and Holloway’s, while Holloway worked and kept the family afloat. Marston wrote. He also “predicted that women would one day rule the world.”

Lepore gets the irony. In 1937, when the American Medical Association endorsed birth control ― a huge victory for Sanger — “William Moulton Marston held a press conference about Amazonian rule, Olive Byrne was typing his books and raising his children,” Lepore writes, “and Sadie Elizabeth Holloway was supporting him. A matriarchy Cherry Orchard was not.”

In the end, Lepore finds in the history of Wonder Woman a critical missing link between first- and second-wave feminists.

“You realize that Wonder Woman is inspired by the suffragists, and early feminists, and birth control activists in the 1910s,” said Lepore. “Well that’s just a source of continuity, and then Gloria Steinem and others of her generation talk about reading Wonder Woman comics in the 1940s when Wonder Woman ran for president and it really affected them and they talk about that in the 1970s. … The missing link is finally there. The 20th century makes sense, at least for me. I needed that link to be there to understand the history of that struggle.”