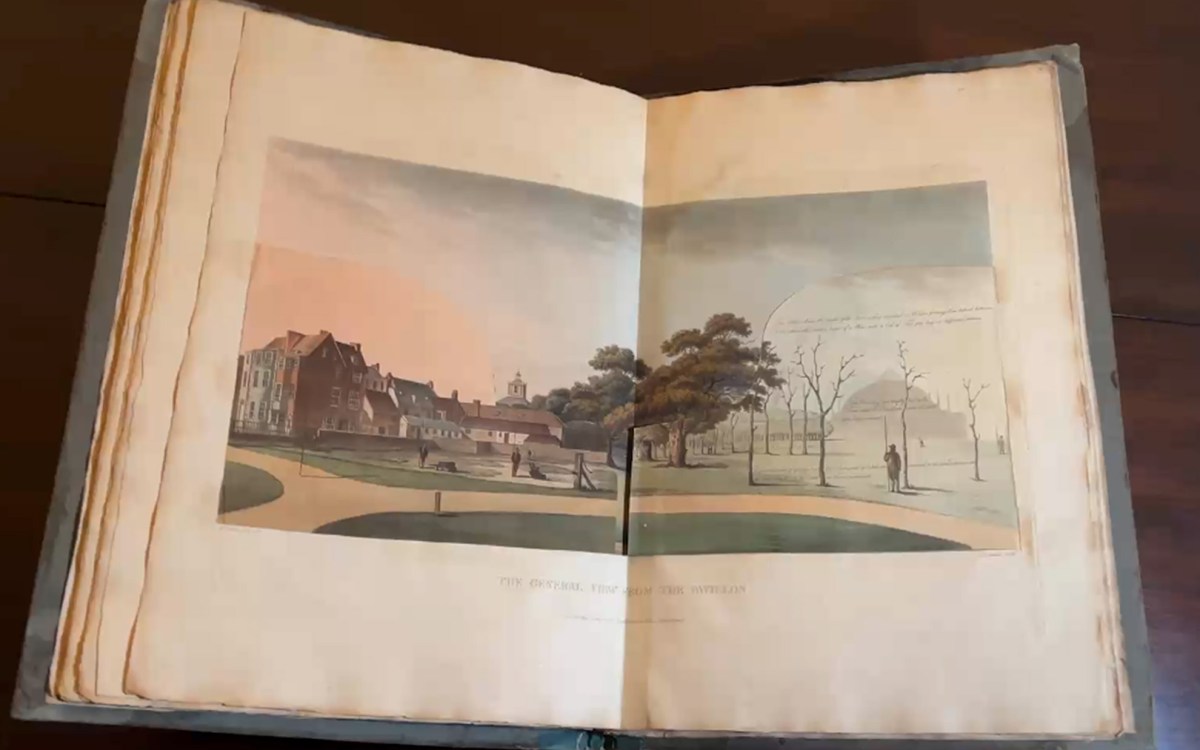

Three filmmakers with Harvard ties have been nominated for Academy Awards for best documentary feature film. The young directors honed their skills as undergraduates in Harvard’s Department of Visual and Environmental Studies. Above are three scenes from Joshua Oppenheimer’s “The Act of Killing.”

Photos by by Joshua Oppenheimer, anonymous, and Caroles Arang de Montis/framegrab

Film as a force

Three Oscar nominees for best documentaries learned their craft in Harvard program

On Sunday, millions of viewers will tune in to the Academy Awards for a chance to see their favorite stars in designer dresses and to learn who will take home the movie industry’s highest honor, gold-plated, 13-and-a-half-inch statuettes fondly known as Oscars.

Three anxious documentarians in the audience who hope to hear their names called have deep roots in a longstanding Harvard program. Joshua Oppenheimer ’96, Jehane Noujaim ’96, and Rick Rowley all honed their early filmmaking skills while undergraduates at the University’s Department of Visual and Environmental Studies (VES), a multidisciplinary program committed, its website says, “to an integrated study of artistic practice, visual culture, and the critical study of the image.”

The young directors are nominees for best documentary feature, each for work about serious international concerns: Noujaim for “The Square,” which charts the ongoing Egyptian revolution; Rick Rowley for “Dirty Wars,” which uncovers covert military action by the United States; and Oppenheimer for “The Act of Killing,” about the mass killings in Indonesia in the 1960s.

(Also holding her breath in the audience on Sunday will be VES alumna Lauren MacMullan ’86, director of “Get a Horse!” which is nominated for an Academy Award in the best animated short film category.)

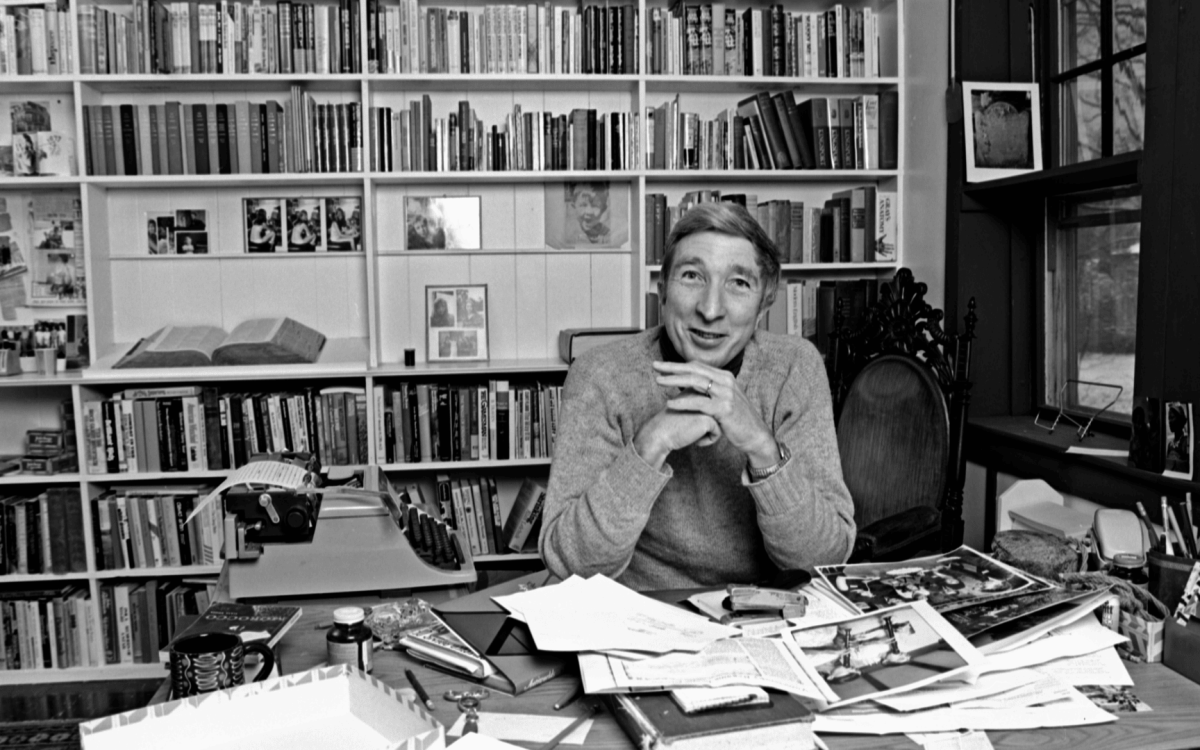

On a recent afternoon, Robb Moss, VES chair and professor of visual and environmental studies, sat in his office, itself a work of art with an imposing concrete column cutting through its center, along with a floor-to-ceiling window. The office and the rest of VES is housed in the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, which was designed by famed Swiss–born architect Le Corbusier.

Moss, credited by many current and past students as an enormously influential mentor, talked about the three documentary filmmakers, including their time at Harvard and their current success.

Rowley, noted Moss, “had a strong sense of and deep engagement with politics, and he understood more than anybody I have ever met that his political sensibility and his desire to make films were twinned and were meant to talk to each other, and talk to the world.”

For Noujaim, it was photography that pulled her into filmmaking, said Moss. She started out working with still photos under the tutelage of Chris Killip, professor of visual and environmental studies. “She had this way of seeing the world and engaging it that I think really started with photography.”

Moss also remembered Noujaim’s gift for collaboration, her ability to connect with people, and her “fantastic sense of what a good documentary story might be. … People trust her, and she doesn’t betray their trust, yet she makes a strong film. She has a real curiosity of what the world is like. She wants to know who you are as a person. She has this interest and sense of empathy.”

As an undergraduate, Oppenheimer had a “wildly imaginative” side that shone through, Moss recalled. “It’s just this very complex view of the world, and that complex view of the world combined with his fantastically imaginative way of representing things, and a fearlessness of image making. All of those things, which are so apparent in ‘The Act of Killing,’ were apparent when he was an undergraduate.”

In addition to their individual skills and talents, Moss said the trio shares a trait critical for anyone hoping to succeed in a competitive industry: a capacity to meet setbacks with tenacity, indeed with “an inability to finish a project until it’s done.”

“It’s very tempting to step out of a project. You are exhausted. You are broke. You’ve exhausted your ideas. You don’t think the film is as good as you think it should be, but you don’t know where it should go,” said Moss. “Then there are people who say it’s not done and I’m not going to finish it until it is done. I think that’s true for the three of them.”

Moss pointed to Noujaim’s work with “The Square” as an example of that tireless drive to get it right. While she was en route to the 2013 Sundance Film Festival —where her film eventually won the audience award in the world cinema documentary category — a new wave of riots erupted in Cairo as protesters demanded that Egypt’s recently elected president Mohammed Morsi step down. Noujaim and her production team returned to Egypt, filmed the protests, and reedited the film with the fresh material.

“She stayed with it,” said Moss, “and the story became far more complex.”

Oppenheimer recalled his formative years at Harvard, saying Moss and other VES faculty “really pushed us to explore what filmmaking can be, ought to be, might be. And for me that meant exploring the boundaries between documentary and fiction.”

“The Act of Killing,” which captures former leaders of Indonesian death squads- reenacting their horrific crimes, starts off as a type of documentary, but ends “in a place of, really, fever dream.”

While Moss has received much media attention recently because of his connection to the three filmmakers, both he and his former students note the strength of the program itself, and point to other faculty who have served as influential mentors.

In addition to crediting Moss, Oppenheimer lauded filmmaker and former VES professor Dusan Makavejev, and singled out Osgood Hooker Professor of Visual Arts Alfred Guzzetti for his patience, gentleness, and his willingness to “say the most cutting and important things that needed to be said.”

Many of those cutting words were aimed at cinematic cliché.

“I have an allergy to cliché that I think I learned from Alfred,” said Oppenheimer. “Anyone who sees ‘The Act of Killing,’ and even my next film that deals with survivors of the Indonesian genocide but hasn’t come out yet, [will see] there is a way in which my work, if it resists anything, it resists sentimentality.”

“Josh was unforgettable,” recalled Guzzetti. “He loved provocation of every kind.”

When screening his film last fall at the Harvard Film Archive, Oppenheimer, who lives in Copenhagen, Denmark, sat in on one of Moss’s classes and was reminded of another critical lesson he learned at VES.

Moss told the students, recalled Oppenheimer, that “the best editing strategy is one which allows your strongest material to be used in the best possible way … editing is not about telling the story you think your material is going to tell, it’s about excavating the material and finding where it really sings and letting it sing its song.”

That type of approach, said Oppenheimer, “is fundamental to what I think filmmaking is.”

Founded in the 1960s, VES has had a strong tradition in documentary filmmaking that has been made even stronger by its ongoing connection with the Film Study Center. Created in 1957 by the groundbreaking ethnographic filmmaker Robert Gardner ’47, the center is the visual arm of Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Today, students interested in documentary film can choose from a wide range of VES offerings, many presented in tandem with the center, including seminars that explore both the history and theory of non-fiction film, as well as hands-on courses that teach how to build a documentary film or video from the ground up.

Guzzetti underlined other strengths of the documentary program, pointing out that the faculty not only includes well-known filmmakers, but also taps into Boston’s powerful documentary filmmaking community. “All of those pieces of the puzzle support us in our efforts,” said Guzzetti.

Photographer and filmmaker Lauren Greenfield is another VES alumna whose work has received critical acclaim. She won the 2012 Sundance Film Festival’s directing award for her documentary “The Queen of Versailles,” which charts a couple’s plans to build a 90,000-square-foot palace in Florida based on the Versailles palace in France.

For help with the film, Greenfield turned to Moss, reconnecting with her former teacher during one of the Sundance Institute’s film labs, a series of intensive workshops for emerging filmmakers. She called him regularly during the final stages of production seeking feedback and advice. “He was always so generous and insightful with his comments,” said Greenfield. “It’s just really special to have that ongoing relationship with a teacher.”

In comparing the VES program to more traditional film schools, Greenfield said Harvard offers students something beyond the art and craft of filmmaking.

“They never taught you a style; they never gave you an assignment that was not open ended. … At Harvard, it’s more about taking the medium and figuring out your voice with it. If you look at ‘The Act of Killing’ and ‘The Square’ and ‘Dirty Wars,’ they are all completely different.”

Moss brings his own passion as a filmmaker to the job. He fell in love with movies while in college. Seeing someone else’s reflection of the world on the big screen, he said, helped him to understand how critical historic developments like the Vietnam War unfolded in real time. After college, work in West Africa and later in the United States as a river rafting guide helped to inspire him toward a career in film.

“All those experiences were very intense, very on the ground, very unmediated … just very experiential and in your face. In a way, that’s a description of documentary filmmaking.”

“Documentary filmmaking seemed a way to go forward and recoup experience at the same time,” he added. “It seemed to me possible that the act of making a documentary film was like going into the world and having it run roughshod over you, and I wanted that.” Moss’s acclaimed films include the documentary “Secrecy” co-directed by Harvard’s Joseph Pellegrino University Professor Peter Galison.

Moss attended an MIT program for filmmaking and started teaching at Harvard in the mid-80s. The job was only supposed to last for a year. But Moss, who found he “had a kind of feeling for teaching,” never left. He teaches nonfiction film classes and cherishes the act of teaching film in an intimate classroom setting.

“When the door shuts in the classroom, I am really happy. It’s this incredible opportunity to think deeply with the students about filmmaking, this thing that I really love.”

Like the three Harvard alumni, Moss will anxiously be watching the awards, albeit from home, and likely less formally attired.

“It’s going to make me nervous. I am going to be nervous for them. Then I will look to the cuts in the audience, and I will see them for the first time dressed up in a way I’ve never seen them before.”

“It’s wonderful to see them getting acknowledged in this way,” added Moss, “but my connection to them and to the work is not through this kind of recognition. Although that’s great, it’s that the work itself is strong and deserving of recognition. To me, it doesn’t matter whether they win or lose. Or, to put in another way, I hope they all win.”