A close-up of the Harkness Tray, designed by Walter Gropius, which was used for about two decades following 1950.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Gripes between bites

Exhibit explores student discontent in history of Harvard dining

Harvard was founded in 1636, and it took only three years for trouble to stir up over food. Nathaniel Eaton, the Puritan college’s first master, was dismissed in 1639, in part because of his misuse of dining funds. Call it a case of defeatin’ Eaton over eatin’.

From the 17th century on, food was often at the center of the plate when it came to student discontent, an interpretation of Harvard history captured in the 1936 book by A.M. Bevis, “Diets and Riots.” There were rebellions over comestibles in 1766 (butter), 1807 (cabbage), and 1895 (Irish stew). One famous food fight at University Hall in 1818 set off a chain of events that culminated in the entire sophomore class of 80 resigning en masse, at least briefly. (Among them was Ralph Waldo Emerson.)

Through Dec. 20, visitors to Pusey Library can look at how food has for centuries turned up in student activism at Harvard — from butter that “stinketh” in 1766 to cage-free eggs in 2011. “Dining and Discontentment” was organized by Carla Cevasco, a Ph.D. candidate in American Studies at Harvard, and by Stephanie B. Garlock, a history concentrator who graduated this year.

The exhibit includes a timeline of Harvard’s dining history, including a few facts that could settle bar bets. For one, forks were introduced to the mealtime experience only after 1710. The college brew house was built in Harvard Yard in 1762, two years before the first Harvard Hall burned to the ground. (There is no connection between the two events.) Waiters were replaced by cafeteria-style dining in 1943, during a world war that had many other leveling effects on American society. And Radcliffe students were allowed to dine in the Houses beginning in 1961, but only at language tables.

Main course

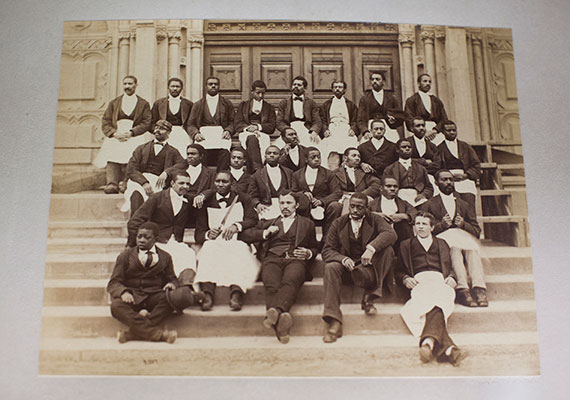

An 1875 photograph of waiters at Harvard’s Memorial Hall. Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

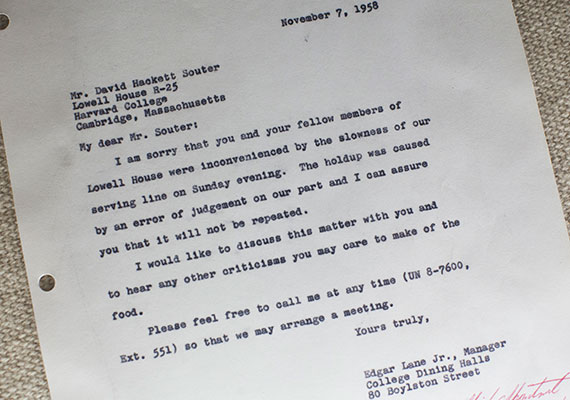

A letter of reply to then-undergraduate David Souter ’61, LL.B. ’66, who in 1958 complained about slow dining room service.

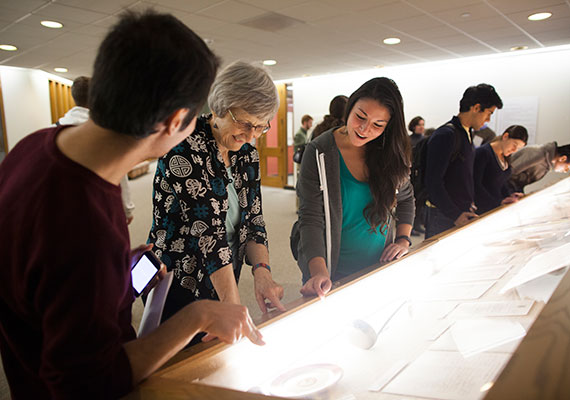

At the October opening of “Dining and Discontentment,” Professor Laurel Ulrich (center) talks with “Tangible Things” students Ozdemir Vayisoglu ’16 and Deborah Montes ’16.

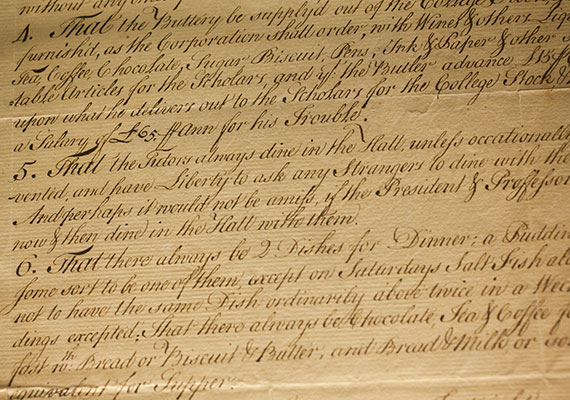

A detail from College Commons records, 1765-1829, one of the Harvard artifacts on display in “Dining and Discontentment.”

Under glass in the exhibit are artifacts that offer material evidence of how things were and how things have changed in Harvard dining. A class ledger for 1689 is on display, with a smooth leather binding. “To know that people were writing on animals at that point in history is very interesting,” said Cevasco. Nearby are the College Commons records for 1765 to 1829, open to pages of rules. Tutors were always to dine in the commons, for instance, and dinner would always include at least two dishes.

Inside another glass case is an 1875 photo of Memorial Hall waiters lounging outside on a set of steps. All are well dressed, many in crisp white aprons, and all are black. Memorial Hall had started offering meals the year before. But next to the photograph is an 1885 Thanksgiving Day menu from Memorial Hall, including a caricature of a black waiter opening a bottle of champagne. The contrast of the caricature with “the incredible dignity of the waiters … is really powerful,” said Cevasco, “and will inspire a lot of important questions on Harvard past — and Harvard present.”

Then there are the plates, cups, and menus from times gone by, among them a vanished artifact called a “Harkness Tray.” This segmented dish — in use from the 1950s through the 1970s — was one example of how a building’s design could extend to the smallest details. The Harkness Commons, a graduate-student dining hall designed by Walter Gropius, opened in 1951. (The modern-making architect taught at Harvard from 1937 to 1952.) The trays, meant to be dishware, were also an example of how form does not always follow function, said Cevasco: the segments of the earliest trays were too shallow to keep foods apart, so people took to balancing dishes on top of the trays.

Of course there is correspondence. In the fall of 1958, Lowell House undergraduate David Souter — later a Supreme Court justice — argued that Sunday evening dining lines moved too slowly. The polite reply is on display too.

“Dining and Discontentment” is one in a series of temporary exhibits assembled for “Tangible Things: Harvard Collections in World History,” a General Education course taught by American historian Laurel Ulrich, the 300th Anniversary University Professor. (Cevasco is one of the course’s teaching fellows.)

Ulrich’s course is co-taught with Chipstone Foundation curator Sarah Anne Carter, Ph.D. ’10, and they are working on a HarvardX version of it now. This summer, the course’s teaching fellows flew to Milwaukee for what Carter called a “material culture boot camp” at Chipstone “to train them to teach with objects,” she said.

Another exhibit for the course explored the economics of botany, the study of plant products exploited for profit. Another was at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, where students looked at a 116-year-old tortilla, a tortoise from the Galapagos, and the science of bird taxidermy.

Ulrich often compares the collections at Harvard to a cabinet of wonders, a tradition of displaying intriguing bricolage that dates to the Renaissance. “We want them to also see [Harvard collections] as cabinets of knowledge, and cabinets of opportunity,” she said.

Part of that opportunity is to break out of patterns of learning that can seem completely dependent on the lecture and the book. “We’re still locked into the 19th century,” said Ulrich of classroom pedagogy. “We’re trying to get people to think across categories.”

Another of her teaching fellows, American Studies Ph.D. student John Frederick Bell, sees great value in breaking out of categories, and in looking at the historical resonance of objects. “We have to disorient them at first,” he said of the students — then insights pour in. Bell remembered a visit to Harvard’s mineralogy collection. “You just look at that, and you have to look at historical questions,” he said. The minerals prompted inquiries beyond science — into the history of mining, for example, and the conquest of the American West.

Getting out and around to collections is all about the insights that rise out of the real, and juxtapositions of the real — such as the blackface caricature of Memorial Hall waiters so near the actuality of the elegant waiters. “It’s got to start with wonder,” said Ulrich of learning. “And that’s the hardest thing to teach.”

“Dining and Discontentment” is on display at the Pusey Library through Dec. 20. Several of the documents featured in the exhibit are held by the Harvard University Archives.