When all turn right, go left

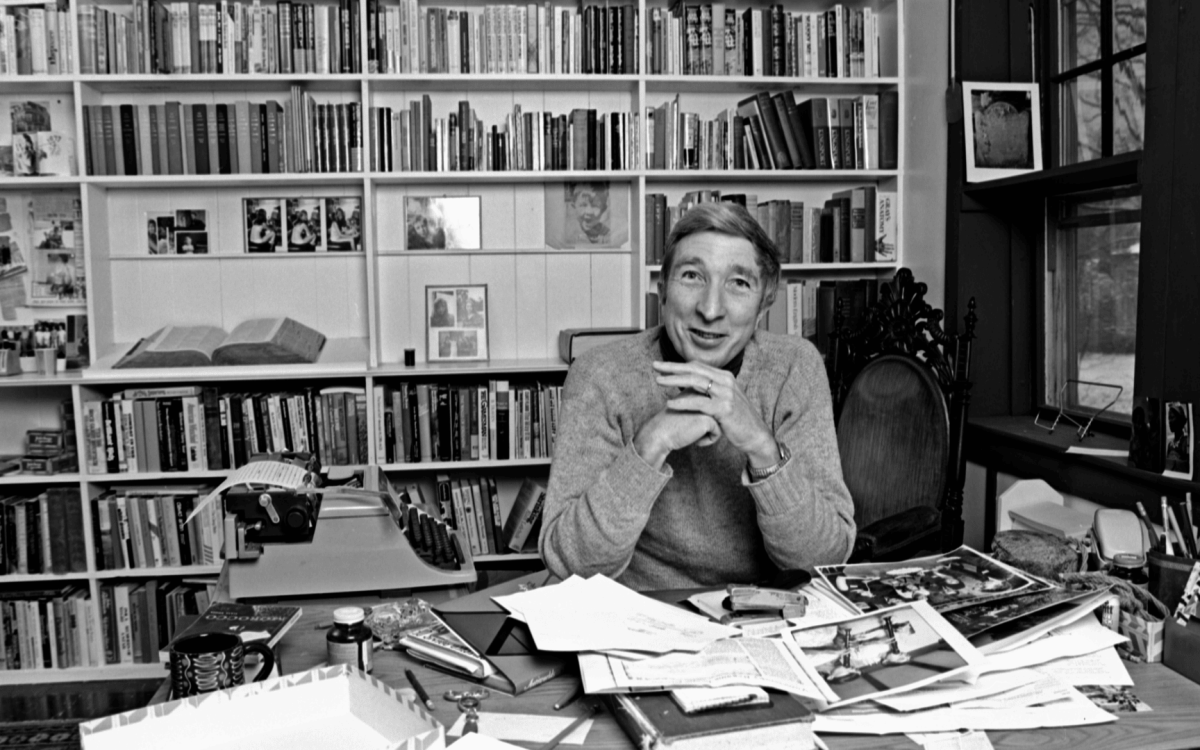

Offbeat visual artist Robert Wilson discusses his craft and career

How long, exactly, is 2 minutes and 37 seconds? If you run the 100-meter dash, it feels like several eternities. If you’re watching an episode of “Breaking Bad,” it seems a nanosecond.

But if you’re among an audience of hundreds waiting for a lecturer to start speaking, and he doesn’t, and he doesn’t, and he just stands stock still at the lectern for 2 minutes and 37 seconds, that is both a very long time and an attention-grabber.

That inventive silence drew the audience in, put it on edge, and was lesson No. 1 from theater and visual artist Robert Wilson. On Friday evening, before a capacity crowd in a darkened Piper Auditorium at the Graduate School of Design (GSD), he delivered a dramatic and discursive talk on how during his years of art-making he has jumped out of the box that long traditions of theater design and direction had set for him, like a trap.

“The reason I work as an artist,” he told the audience, “is to ask questions.” He tries not to follow rules but to crack them open over the knee of imagination.

The 72-year-old Wilson is an experimental theater producer, director, and designer. His list of collaborators includes William S. Burroughs, Susan Sontag, Lou Reed, Tom Waits, Allen Ginsberg, and Philip Glass, with whom he created a signature work, “Einstein on the Beach.” Along the way, Wilson has also been a painter, a sculptor, a video artist, and a lighting designer who worked with light as if it were paint.

As a relentless experimenter, he started his lecture off with no lecture at all, just the minutes of silence. You might not be surprised that such an artist has cast people off the street for plays, or that in his work “A Letter for Queen Victoria” (1974), his 90-year-old grandmother from Texas played the queen. He once directed an overnight production 12 hours long, and another that lasted seven days and had a cast of 580. During the shah’s rule in Iran, Wilson directed 5,000 soldiers to whitewash a hilltop, simulating snow.

Robert Wilson’s experience in theater offered a lesson that spoke to student designers, who may be tempted to make buildings and landscapes that are works of art instead of art that works.

In “The Life and Times of Sigmund Freud” (1969), the man playing Freud was a retired housepainter whom Wilson had met in Grand Central Station. The set included a hanging chair; the action called for a turtle to take 37 minutes to walk across stage. “Many people said the work had nothing to do with Freud,” Wilson told his GSD audience. But he disagreed, seeing it as a parable of the psychoanalyst at age 68, when he fell into a depression and was diagnosed with cancer. “It’s not the kind of story you’re going to get in the history books,” he said.

Similarly, Friday’s two-hour talk was not the kind of lecture you would usually get at Harvard. Aside from the prefatory silence, the audience also got shouts, red-faced fits of coughing, and mimed threats to kill. No one coming out of theater or music school, he complained, knows how to walk while on stage, or simply stand still.

Wilson’s appearance was the third in a series of “sensory media platform” public lectures that began last year. The idea is to invite practitioners to remind students that what they do demands art as well as technology.

“What we would like to bring more to the foreground is imagination,” said Silvia Benedito before the lecture. She is an assistant professor of landscape design at GSD and a member of an informal sensory media platform committee at GSD. “Wilson is so demonstrative,” said another committee member, Allen Sayegh, an associate professor in practice of architectural technology. “There is no doubt [the audience] will get something out of this.”

During the talk, what the audience got was a pingpong summary of Wilson’s career in theater, from the days he arrived in New York from Waco, Texas, to study architecture at Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute. Wilson had strong opinions right away. Broadways shows, mainstream opera: no. George Balanchine, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage: yes. They created staged movement and light and sound that expressed “so much freedom,” said Wilson.

His early experience with dance led him to a core idea. “I start with movement,” said Wilson, “and from the movement I let the sound come.”

Doing the unexpected was inspired early too. Wilson had one favorite professor at Pratt whose lectures were accompanied by a slideshow of unrelated images. He recalled the final exam, with the professor saying, “Students, you have three minutes to design a city.” (Wilson drew an apple; within it was a crystal cube, “to reflect the universe.”)

There was another lesson in the exam, he told the audience of student designers: “The most important thing is, you have to think quickly.”

The crystal sphere was an emblem of another core idea to Wilson, that light can make or break a play, and that it has to be designed as if with a brush, and with movement too. (“Light,” he told the audience, “is like an action.”)

Then there is “mega-structure,” the grand spatial idea behind planning anything complex. “How do you write a play that is seven hours long?” Wilson asked. “How do you design a city?” You start with a structure, which for Wilson consisted of the grids and fast sketches he made for the audience. In writing the music for “Einstein on the Beach,” Glass worked for months with Wilson’s drawings, one by one, propped up before on the piano. From structure, said Wilson, comes content, like Glass’s music. “Without structure, I don’t know what to do,” he said. “I am lost.”

Time is a factor, too. Wilson and Glass created a structure for “Einstein,” and determined it would be 4 hours and 46 minutes long. At other times, said Wilson, he was faced with a production of 100 episodes, each 30 seconds long.

His experience in theater offered a lesson that spoke to student designers, who may be tempted to make buildings and landscapes that are works of art instead of art that works. “Ban the schools of theater decoration,” shouted Wilson. “We do not need them. Theater should be architectural.”

Artists of every stripe have to be ready for critics too, Wilson said. He recalled taking a seat next to Arthur Miller during a revival of “Einstein on the Beach.” The playwright, who had no idea who Wilson was, turned and said, “You know, I don’t get it.” Ten minutes later Miller walked out.

Artists have to be ready for a slump in confidence. “Nine times out of 10 you think: This will never work,” said Wilson, looking back over 50 years of art-making. “So you just keep working. Discipline helps.”

In times like that, being contrary helps too, he said, sounding just like a man who started a talk by not talking. “You think of the wrong thing to do,” said Wilson. “Then you do that.”