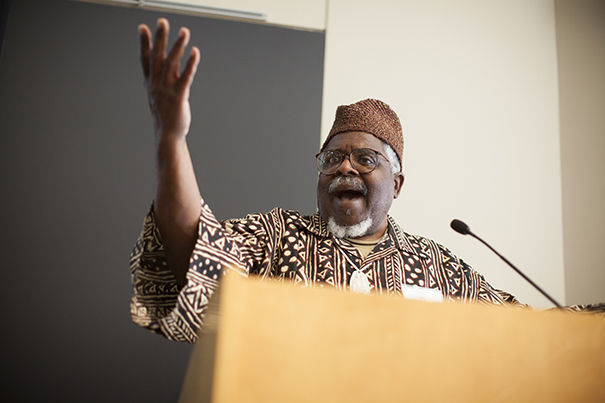

Through the “Divine Space and Sacred Territories” conference, the visiting scholars from New England, New York, Georgia, Florida, and Nigeria touched on Yorùbá, its Caribbean cousin Vodou, and other practices from humankind’s genetic ancestral home. “We are all Africans,” said keynote speaker Baba John Mason (pictured).

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The world as sacred

Conference focuses on beliefs, influences that are key to Africa’s religious diaspora

“Divine Space and Sacred Territories” sounds like something you find in church. But this felicitous phrase was the name of the inaugural conference of Harvard’s African and Diasporic Religious Studies Association, the only such group in North America.

About 20 scholarly presenters and 150 listeners gathered Friday at Boylston Hall to discuss this modern scattering of ancient religious traditions. The teachings are “always blending and cosmopolitan,” said association director and Harvard doctoral student Funlayo E. Wood, and are “formidable forces in world region. They heal what is broken, balance what is askew.”

What has this religious diaspora done to influence modern spiritual practice? A lot, the scholars said, including providing a sense of the Earth as sacred and healing. And what can such religious influences — most of them from a preliterate era — offer current spiritual practice? Again, much, say the experts, including a sense that the divine may reside in everyday objects, in movement, and in the body itself.

Through the day, the conference scholars from New England, New York, Georgia, Florida, and Nigeria touched on Yorùbá, its Caribbean cousin Vodou, and other practices from humankind’s genetic ancestral home. (“We are all Africans,” said keynote speaker Baba John Mason.)

“It’s not tired old things that have been repeated,” said Francis X. Clooney S.J. of the conference’s fresh perspective on modern spirituality. “You’re bringing new things.” (Clooney, who offered a few words to the audience early on, is director of the Harvard Divinity School’s Center for the Study of World Religions, a major conference sponsor.)

Such practices offer timely lessons. For one, they bring to bear those natural entities deserving honor and protection, including the Earth itself. “Destroying the land equates to human genocide,” said presenter Yoknyam Dabale, a Nigerian-born blogger who is a master’s degree student at Boston College.

The conference began with a libation based on the sacredness of Earth itself by Ifa and Orisa practitioner Awo Oluwole Ifakunle Adetutu Alagbede, chief priest of the Ile Omo Ope shrine in Harlem. “Christians look toward the sky,” he said of his water blessing. “We look toward the ground.”

Dabale added that female spirits are custodians of the land. It was a reminder of another lesson from Africa’s religious diaspora: the spiritual power of the feminine. Within Christianity, at least, that note remains muted. Dabale said that both modern Africa and the Americas are in need of the balancing, life-giving spiritual power of the feminine.

Also deserving of honor and protection, according to these diasporic traditions, are ancestors, who represent the wisdom of the past; elders, who represent the wisdom of the present; and communities, which represent the wisdom of cooperation. That well-ordered life is embodied in the termite mound, said Mason. The shape of these towering cylindrical mounds is echoed in sacred mud structures seen throughout the Yorùbá homeland of northwest Africa.

Historian Suzanne Preston Blier, whose reflections on African sacred beliefs opened the conference, remarked on the same ubiquity of these architectural features, these “hollow residences of spirits,” she said, that attract protection and good will. Blier, who is the Allen Whitehill Clowes Chair of Fine Arts and professor of African and African American Studies, also talked about mapping sacred space using modern geographic information systems (GIS) and computer technologies. An interactive project is already under way, she said, in the Africa section of Harvard’s WorldMap.

Also deserving of care are our own bodies. “Your body is a temple — ritual space that you design,” said Mason, a Yorùbá priest and founder of the Brooklyn-based Yorùbá Theological Archministry.

The body is in special need of protection these days, said therapist, interfaith minister, and Yorùbá priestess DeShannon Bowens, especially for “cultural groups with a history of violent oppression, (where) traumas on the body go back to the time of their enslavement.” A sexual assault takes place every 2.5 minutes in the United States alone, she said, adding that one in every three or four girls (and one in six boys) will be sexually assaulted in their lifetimes.

“It violates our bodies as sacred space,” said Bowens of sexual trauma, which she tries to heal with both psychotherapy and traditional spiritualism. “These wounds go back thousands of years.”

Bowens, founder of the Ilera counseling service (the word means triumph and health in Yorùbá), was among the many practitioners, artists, and scholars who said that African diasporic beliefs bring another lesson to the West and to Christian nations at large: The body and the spirit are not in opposition. They are not in a dueling, dual state, as Augustine held (and as Plato had argued much earlier). They complement one another, and interweave — as Vodou holds — like Earth and sky. Thinking that the body and spirit are opposed, like good and evil, said Bowens “is one of the hardest things to get over. You don’t even have to be a Christian.”

In the conference’s four panels, and among its 14 presenters (12 of them women), the lesson of the body’s spiritual power was most evident. Scholars stood behind the podium, but they moved, shouted, sang, and danced, too. Maya James was among the last trio of presenters, all performers from the collective Lukumi Arts in New York. Her paper was a riff, sermon, shout, and a scholar’s interweaving of Aristotle and Shakespeare with the Pentecostal. Her work compared women sitting placidly in church to peaches in a jar. But before long, the peaches “shook loose,” said James, the preacher was leaping from the pulpit, and “it is holy bedlam in this space.”

Holy bedlam provides a lesson for churches everywhere, she said. “Divinity can exist anywhere, even when it’s not invited.”

The conference seemed to say: Bring the body back to spirituality. It also seemed to say: Bring back the portability of the sacred. In a gathering whose main theme was divine space, a lesson emerged from Africa’s spiritual diaspora: In a world of churches, temples, and mosques, the sacred does not require a building; it is present in everyday life.

Blier talked about sacred groves, pathways littered with glittering mica, roots, stones, and trees with meaning. Clooney talked about sacred spaces in the world created by tragedy, like ground zero in New York, and about Harvard’s own “quasi-sacred spaces,” including Memorial Church, Memorial Hall, and the glittering toe on one foot of the John Harvard statute, a lucky touchstone for thousands of tourists ever year.

Mason talked about the little shrines in the home of every Yorùbá believer, which provide living space for orisha, the traditional deities of wisdom, sexuality, healing, and other powers. “This is maybe the one strength that keeps us from being Catholic or being Protestant,” said Mason. “We did not put orishas in a separate place that we may visit. Rather, they are in my house. … My relations to God are always close at hand.”