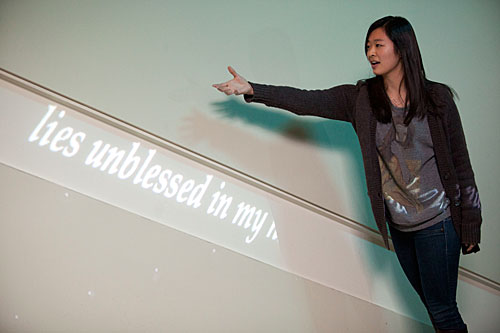

Greg Yang ’14 demonstrates his skills at the turntables after being shown the “one-click flair,” a fast finger twitch method of isolating a single sound while spinning two records.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Arts prove intensive

January session allows students to tap interests, talents

DJ Super Squirrel helped students to rock the house. Television producer Carlton Cuse ’81 connected undergraduates to their inner TV genius. The Harvard Breakers tore up the floor with hip-hop dancers in training.

Across the campus this January, students collaborated with artists and other professionals to sculpt, write, laugh, dance, produce, perform, and play during Harvard’s Wintersession.

The University’s revamped academic calendar not only offers students the chance to unwind during break without the worry of looming papers and exams, it also provides them with a relaxed week back at Harvard where they can engage with a range of inventive programming before classes begin. Many seminars and workshops are artistic and connect students with areas or aesthetics they might never explore when in full academic mode.

“They get to step outside the day-to-day requirements of living in an academic environment and treat it like a playground, and let their minds run in an open and free way,” said Jack Megan, director of Harvard’s Office for the Arts (OFA), which sponsored a series of arts intensives with alumni in collaboration with the Harvard Alumni Association. “It’s creative play, but that feeds so much, including the way we learn and engage with other kinds of learning.”

Among the myriad OFA offerings, students took a turn creating a show for the popular doctor drama “House” under the guidance of Harvard graduates Cuse, executive producer and head writer for the hit show “Lost,” and Monica Henderson Beletsky ’99, a writer for the shows “Friday Night Lights” and “Parenthood.” In Sever Hall, the pair walked the undergraduates through the creative brainstorming process, discussing ideas and exploring plot themes and narrative arcs. Using suggestions from the students, they settled on a storyline involving the main character House and his archrival, Moriarty, House’s visiting nephew, and a young boy with a penchant for swallowing things like his parents’ car keys and an engagement ring.

“It’s fun to see the students take some of these concepts that are very specific to the craft of television writing and run with them and see where their imaginations take them,” said Cuse.

He praised the University for its efforts to increase the presence of the arts on campus.

“Harvard has recognized the need to increase the exposure of students to the arts, and I think it’s enormously valuable, whatever you end up doing in your life.”

Students curious about what it takes to score a major motion picture turned to music industry executive Robert Kraft ’76. Using clips from movies such as “Ice Age,” “Night at the Museum,” and “Rise of the Planet of the Apes,” Kraft had the group listen carefully to how a pulsing score or a line from a popular song can heighten a film’s atmosphere.

If the job is done right, said Kraft, “you don’t notice the music at all.” It becomes just part of the overall film experience. While a strong music background and an ability to tell a story with music are key, said the music executive, collaboration in an industry with big personalities and big money on the line is paramount.

The work can involve pleading with musical icons like Paul McCartney for the rights to a song, or convincing a composer to rescore a film in a few days, a process that typically takes about two months. Such was the case with “Rise of the Planet of the Apes,” when the initial soundtrack was deemed too melodramatic once the digitally generated apes were edited into the film.

“Your political skills,” Kraft said, “are the No. 1 attribute.”

For Andy Borowitz ’80, comedy is king.

“The funny people go into comedy; the not funny people go to law school. So now’s the time to decide,” joked the humorist and author to a crowd in Boylston Hall during a talk titled “Comedy: The Career.”

His parents, he said, assumed he would take the law school route, but his love for comedy intervened. While at Harvard, he wrote, performed, and eventually became president of the Harvard Lampoon. Borowitz encouraged students interested in his path to first “find out if you are a funny person.”

“It’s possible that you’re occupying some kind of underground niche where no one understands your comedy. That’s what we call failing.”

To succeed, you have to write on a daily basis, become passionate observers of the world, and, above all, he said, “follow your bliss.”

“This is my bliss. I don’t feel like I am working; I am having fun every day.”

Arts @ 29 Garden hosted arts intensives based on the connection between the digital age and the arts, including one for wannabe spin masters.

While turntables are still a critical part of a deejay’s repertoire, much of the music crafted for clubs today employs computers and sophisticated software. Sarah Hankins, a.k.a. DJ Super Squirrel, a Harvard graduate student in ethnomusicology who studies the deejay culture and clubs in the Middle East, used the popular computer program Ableton to help students create a high-tech mix tape during her intensive “Learn to DJ.”

“With two hands and two turntables, you could only play two sounds at once. Now it’s like you have the equivalent of an infinite number of hands,” said Hankins.

Using the computer program, students chopped up songs and then merged the sections back together to create their mixes. Their ultimate goal was a creative sound that keeps the beat seamless and steady.

Hankins also added a historic dimension to the weeklong session, paying homage to people like Grand Wizard Theodore, the inventor of scratching, the technique of manipulating one record over another by scratching it back and forth under the needle, and to New York’s South Bronx of the 1960s and ’70s, where the deejay art form, an import from Jamaica, took root and evolved.

“I feel like anyone who is going to deejay needs to know that history. Otherwise, you are just faking,” she said. “You want to know the history of the art form.”

But being a deejay also has broader implications, said Hankins, who compares the art form to an increasingly interconnected worldview.

“This is the future of world culture to me. … This whole remix aesthetic, that’s what we all do now, that is what the world is doing, whether in the realm of music or art or medicine or literature — it’s all about sampling” from something else. “The more you understand how to remix, the more you understand how the world is working.”

Hankins also went old school with the class, helping students to perfect their vinyl scratching techniques. She carefully walked sophomore Greg Yang through the “one-click flair,” a fast finger twitch method of isolating a single sound while spinning two records.

“It’s pretty awesome,” said Yang, as he worked the side-by-side turntables. “It feels like you’re the man.”

Down the hall, sophomore Bex Kwan practiced her inner moss. Flopping her body over a railing, she remained motionless for a minute, before slowly standing and raising her arms in the air, transforming from the small soft plant into a swaying fern. Kwan was part of a seminar called “The Technology of Performance.” Two New York-based video designers led the session and helped students to create performances that incorporated movement with audio and video components.

“I’ve trained as a photographer and actor,” said Kwan, a Dudley House resident and VES concentrator. “They are completely different fields, but I’ve always wanted to merge them. … Finding people who are as passionate about where these media come together is really amazing.”

The theme for the intensives at the Garden Street space encouraged students to collaborative on issues involving the arts, media, and technology, said Lori Gross, associate provost for arts and culture. “By exploring identity in the digital age through text, visual imagery, and performance, students were able to intensely focus on their own innovative artistic explorations.”

Movement and motion were also part of Wintersession’s eclectic mix. At the Harvard Dance Center, students worked with renowned choreographer Christopher Roman to create a work for the Harvard Dance Program’s spring show. In the Lowell House dance studio, the Harvard Breakers, a student-led dance troupe specializing in street styles of hip-hop dance, led a five-day beginner boot camp.

At Agassiz House, an aspiring composer was reveling in an intensive that teamed her with members of the Silk Road Ensemble, the collection of musicians from around the world, led by cellist Yo-Yo Ma, who explore the cultural traditions of the ancient trade route.

At Harvard as part of an ongoing residency, the ensemble practiced new compositions and mentored a small group of students who created projects inspired by the group’s work.

Freshman Stella Fiorenzoli has wasted no time connecting with Harvard’s art scene. She partnered in the fall with the ensemble and was back for Wintersession, creating a mini-composition based on Tibetan and Indian folk tunes and written for the ensemble’s shakuhachi, a Japanese bamboo flute, and the pipa, a Chinese stringed instrument.

A classically trained pianist and cellist, Fiorenzoli called her work with the ensemble and the exposure to so many types of instruments and music “inspiring.”

“There is this world of instruments that have these unique sounds and tones and that really should be … explored more in the music that we listen to today. This has been one of the greatest experiences that I have had at Harvard so far.”