There are also a few common sense restrictions on archival materials, “in many cases because of fragility,” said Houghton assistant curator Heather Cole. That includes items that predate Christ, like the extensive collection of documents on papyrus. It also extends to the John Keats manuscripts and to the Emily Dickinson family books that are printed on brittle stock.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The history at Houghton

A tour of Harvard’s modernized ‘Treasure Room’

Harvard’s neo-Georgian Houghton Library, which occupies the first building at an American university designed to house rare books and manuscripts, was built in 1942 with a gift from Arthur A. Houghton Jr. ’29, and was quickly celebrated for its innovative climate-control, shelving, and air-filtration systems. Soon Houghton was a national model for similar archives.

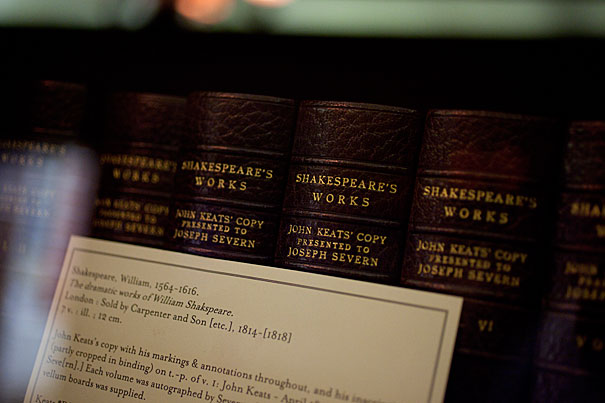

Houghton’s physical antecedent was Harvard’s fabled “Treasure Room” at the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library. This grand exhibition space opened in 1915, in what is now the Periodicals Reading Room. Literary and historical gems went on rotating display there, including quarto editions of Shakespeare and first-edition works by John Milton.

The Treasure Room was expanded in 1929 when gifts of rare books to the University seemed to come in a sudden flood. But by 1938 Harvard library director Keyes D. Metcalf was lobbying for a separate space for Harvard’s rarities, in part of his campaign to decentralize collections and to stem growing pressures at Widener.

When Lamont Library opened in 1949, one underground level was given to the ever-growing Houghton. And when the Nathan Marsh Pusey Library opened in 1976, Houghton acquired even more space. Today, staffers freely traverse the underground portions of this triumvirate of libraries, moving up lighted ramps from one secure space to another. (There are also underground connections to Widener.)

This modern expansion of Harvard’s collection capacity, from 1942 on, resulted in today’s locked-down, climate-controlled warren of literary treasures at Houghton. There are rooms devoted to paper artifacts from poets John Keats, Emily Dickinson, and Amy Lowell, as well as a suite of materials related to 18th-century English essayist, logophile, and literary critic Samuel Johnson.

In Houghton’s deepest sub-basement, thousands of feet of shelves are lined with neat black boxes — the resting places of eye-popping literary treasures, including the Emerson family papers. Leslie Morris, Houghton’s curator of modern books and manuscripts, carefully opened one slipcase box earlier this year. Inside was the 1856 journal of Ralph Waldo Emerson, its pages alive with bold handwriting. Some passages were crossed out, a sign they had been mined for literary product elsewhere. “He used his journals,” said Morris, “as his quarry.”

***

Each generation of literary materials presents its own challenges, said Morris, who led Harvard journalists on a private tour of Houghton. Keats, for instance, wrote with “iron gall” ink, whose corrosive chemical profile, as acidic as lemons, can eat holes through paper. This ink formulation, in use from the 12th through the 19th centuries, can degrade over time or even destroy a manuscript.

A more modern challenge is the fragile chemistry of fax paper. It’s a signature problem in the voluminous Gore Vidal papers now housed at Houghton. To this day, the prolific author refuses to use email, and over the years has sent and received volumes of faxes. But facsimiles quickly fade, said Morris, and there is no reliable way to recover these “fugitive” images, except to copy what is still readable.

The Vidal collection, one of Houghton’s largest 20th century holdings, arrived over the past decade in 400 cartons and took almost five years to process. It contained a reminder of another major challenge for contemporary archivists: film, videotape, and audiotape. The Vidal archive includes thousands of feet of magnetic and electronic material in a span of formats, some of them archaic. It’s an issue that archivists grapple with increasingly.

By contrast, the John Updike papers include little such material, and could be mistaken for papers from an earlier era. The author himself packed and labeled his yearly donations in neat cartons. “He could have been an archivist,” said Morris. “He was very organized in his habits.”

***

Modern literary archives also have their minor challenges. Take a humble, but potentially ruinous, issue like a favorite brand of transparent tape. Some brands dry and flake off as they age; others turn gummy.

Earlier this year Houghton archivists sent a batch of at-risk Updike pages to Harvard’s Weissman Preservation Center. Experts there try to fix or control the runaway chemistry of tape, glue, paper, and photo surfaces.

There is a further modern challenge for archivists: the fate of the computers and word processors on which much of today’s literature is produced. Pioneering archivists at Emory University have author Salman Rushdie’s old Mac computers, and are exploring ways to mine text documents, emails, and other artifacts of data. It’s the kind of digital archaeology that one day will be a common archival pursuit.

Updike wrote first drafts of his fiction in longhand. He had a computer too, but it’s not in the archive, said Morris. “Mrs. Updike continues to use it.”

Other archival challenges are timeless, including an author’s wish for privacy, and the restrictions that grow out of that wish. The Vidal archive is an open book, for instance, with two exceptions: A World War II diary requires special permission to see, and there is a 10-year moratorium on the author’s financial records.

There are also a few common sense restrictions on archival materials, “in many cases because of fragility,” said Houghton assistant curator Heather Cole. That includes items that predate Christ, like the extensive collection of documents on papyrus. It also extends to the John Keats manuscripts and to the Emily Dickinson family books that are printed on brittle stock.

When the originals are too fragile to handle, “we like to have a surrogate available,” said Cole — often a digitized version. But this is not always possible. Why? That reveals the ultimate challenge to archivists everywhere: staff time and money.

In receiving new material, archivists often have to winnow collections for irrelevant material. “We try to see it doesn’t come in the door,” said Morris, who turned down Vidal’s receipts for dry cleaning. “Sometimes all that noise in an archive can drown everything out.”

Some of the noise gets through, however, in Houghton’s minor collection of artifacts — including jewelry, spectacles, even pulled teeth. The library has a teacup of Dickinson’s, a pair of magician Harry Houdini’s handcuffs, and a pencil made at the factory owned by the family of author Henry David Thoreau. It has author-related coins, buttons, glass, and statuettes, all of which arrived as separate gifts. Some of these artifacts wind up in Houghton’s “Z closet,” the space for odds and ends named after Houghton’s standard cataloging designation for non-paper materials.

Others are shelved in boxes, including the library’s extensive collection of death masks — providing a way of seeing authors through more than their manuscripts. Should they chose, scholars can ask to view, among others, those of James Joyce, William James, and Walt Whitman (whose beard and chest are included).