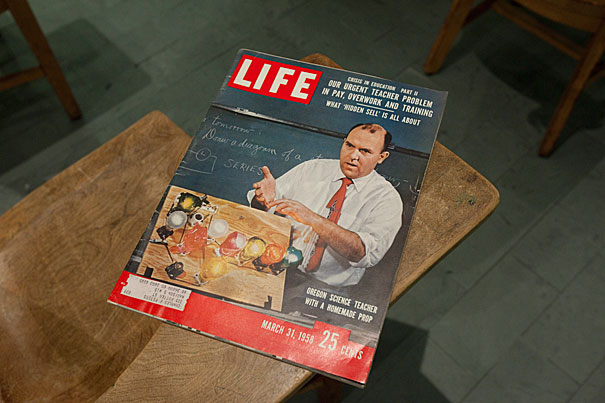

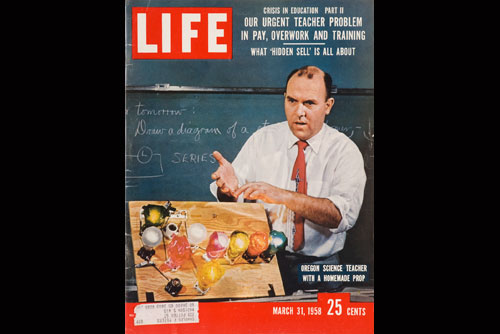

At the exhibit “Cold War in the Classroom,” you can flip through the Life magazine issue of March 31, 1958, and get a glimpse of pre-Sputnik fear: an article about the “underdog profession” of high school science teaching, in peril during a race to domination against the Soviets.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Cold War fever

Exhibit uses maps, texts, video to show how fear entered classrooms

On Christmas Day 1991, the hammer and sickle flag of the Soviet Union that had flown for 70 years was lowered at the Kremlin for the last time. And after 45 years of proxy wars, political rancor, and military tension, the Cold War was over.

Now the Cold War is back, at least on display at Harvard. An exhibit of artifacts from the tense period after World War II, when the communist Soviet Union and the democratic West faced off with nuclear arsenals at the ready, opens today, hosted by the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments.

“Cold War in the Classroom,” which will run through Dec. 16 at Science Center 251, is a time machine of global maps, scientific instruments, dated textbooks, and audiovisual materials that serve up equal parts patriotic corn and science pedagogy. Such remnants of material culture are often reminders of how military and political tension once so explicitly found their way into American classrooms.

It’s the right time to look back, said collection director Peter Galison, Harvard’s Joseph Pellegrino University Professor. “We’re at a moment now when the Cold War no longer seems like something inevitable,” he said. “When I was growing up, the Cold War seemed like a permanent thing.”

With the Cold War now firmly in the past, “it’s a moment when we can reflect,” said Galison, when we can ponder that vanished “mirror world of opposition that shaped a lot of our art, our science, our universities, and our military.”

The exhibit’s artifacts of Cold War culture — the instruments, movies, music, textbooks — can help with that reflection by supplementing text-based explorations, said Galison. “There are other ways we understand the world, and the visual is one of them.” (His own films, with Robb Moss, Harvard’s Rudolf Arnheim Lecturer on Filmmaking, include “Secrecy,” a 2008 Sundance Film Festival selection, and “The Ultimate Weapon,” a look at the hydrogen bomb.)

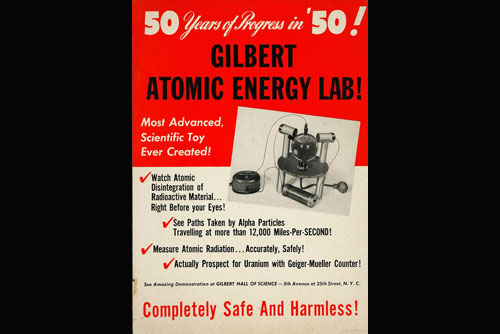

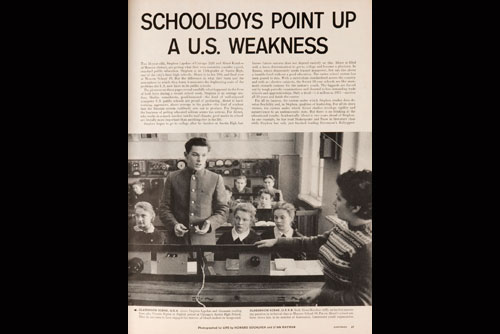

The exhibit invites viewers back to school. You can stand at a lab bench and look through an A.C. Gilbert Co. chemistry set from the era. (The radium sample from the original — “completely safe,” its makers said — has been removed.) You can sit in a row of old writing chairs (rescued from a Harvard basement) and peruse a physics textbook from the time of atom bombs and Dwight Eisenhower. Or you can flip through the Life magazine issue of March 31, 1958, and get a glimpse of pre-Sputnik fear: an article about the “underdog profession” of high school science teaching, in peril during a race to domination against the Soviets.

At one of the same desks you can put on earphones, tap on an iPad, and call up any of 100 didactic films going back to the earliest Cold War days in the late 1940s. (The experimental software used, called Zeega, is an ongoing open-source project of metaLab (at) Harvard.)

You can watch an instructional film of the era projected on a glittery screen in another corner of the exhibit. “Duck and Cover,” released in 1952 for a primary-school audience, suggests how to survive an atomic attack. It stars Bert the Turtle, a cartoon safety icon who ducks inside his shell.

The co-curators of the exhibit, both in their 20s, are too young for that era, but they remember the same classroom drill that had children crouching under desks. It was tied to earthquakes for California native Jeremy Blatter, a Ph.D. candidate in the history of science. And it involved tornadoes for Christopher Phillips ’04, Ph.D. ’11, a lecturer on the history of science who grew up in Georgia.

“The Cold War from our point of view is the demise of the Cold War,” said Phillips, but the short distance in time makes the era more available to scholars.

So does the wealth of Cold War material that is turning up on the Internet, said Blatter, much of it in the public domain. When working at the Harvard Film Archive, he watched hundreds of instruction films from the era, many of them now a rich source for artists and historians of material culture.

Phillips was surprised to discover that the Cold War in the classroom was not all about math and physics. It was also a time of rapid pedagogical innovation, even in the life sciences, starting with films and filmstrips and better instrumentation for classroom demonstrations. The A/V era — a foreshadowing of the computer-driven multimedia teaching tools of today — was boosted by the energy of the Cold War era.

Blatter called the exhibit’s material artifacts “fascinating statements of an era.” One such comes in the fine print on “A Factual and Pictorial Map of World Freedom,” a 1950 creation by pictorial map pioneer Ernest Dudley Chase, a native of Lowell, Mass. Blatter had a tiny entry blown up for viewers — the one in which Chase pointed out the exact deep spot in the Pacific Ocean where all “commie” ideas could be buried.

But those ideas, when harnessed to science, could provoke fear. Collection administrator Jean-François Gauvin pointed out one exhibit caption for “USSR State School.” It read, “Americans often described the Soviet education system as brutal, communistic, and anti-democratic, but also as worryingly effective.”

Over time, that worry has become, in part, admiration for an era’s lost aesthetic. In one corner of the exhibit, you can see the artifacts of a vanished classroom world: a folding turquoise movie screen; a stout, pig-shaped Bell & Howell 35mm slide projector; and a stack of yellow film cans marked “Somerville High School.” (“We were excited that a lot of the material was local,” said Phillips.)

The exhibit also touches on Harvard’s role in the Cold War’s pedagogical fallout. For example, the Harvard Project Physics (1962-1972) challenged the common narrative of physics as being the pursuit of the military. It was aimed at establishing a physics curriculum for U.S. secondary schools.

Two of its three directors were on the Harvard faculty: Physics Professor Gerald Holton (now emeritus) and the late Fletcher G. Watson, then a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Phillips hopes that visitors to “Cold War in the Classroom” come away thinking of the mundane in a new way. “A map from the 1950s,” he said, “is not just a map,” but is a clue to the values and perceptions of the past.

Blatter agreed. He called sitting at one of the exhibit desks a “historical thought experiment.”

Cold War: A closer look

Nuclear physics at home

Nuclear physics at home, including “completely safe” radioactive samples! The A.C. Gilbert Company was an important maker of sets (chemistry, physics, microscope, etc.) and other educational toys in the 1950s.

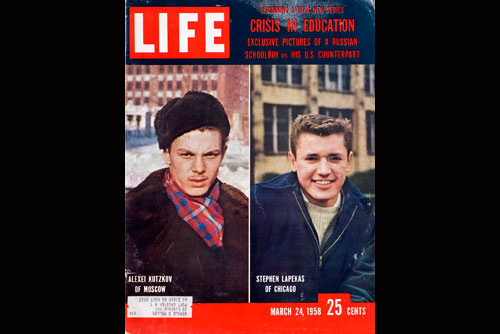

Schoolboy competition

Comparing school life in Moscow and Chicago in the 1950s.

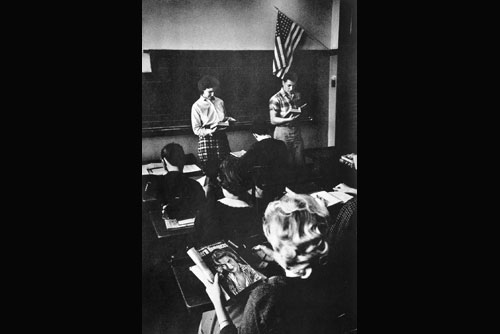

Modern romance

A “typical” (and clearly staged — notice the open magazine) image of an American classroom during the Cold War.

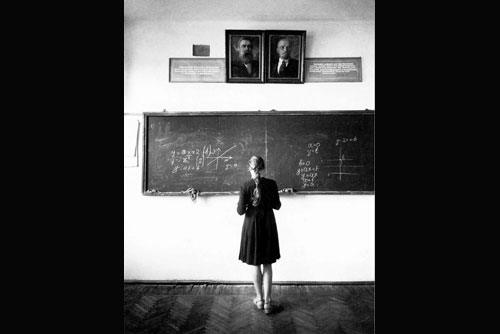

Schoolgirl

Americans often described the Soviet education system as brutal, communistic, and anti-democratic — but also as worryingly effective.

Chemistry set

This A.C. Gilbert chemistry set from 1936 is indicative of the ways the lines between commercial enterprises and academic science continued to be blurred.

Power supply

The “Project Physics” course grew out of a Harvard initiative in the late 1960s to teach all students physics, not just those who would go on to careers in science. This power supply is part of a set of instruments made by Damon Engineering, specifically produced and marketed for the “Project Physics” course.

‘Crisis in Education’

LIFE magazine’s 1958 series uncovered disparities and problems that are still vocalized by 21st-century education reformers.

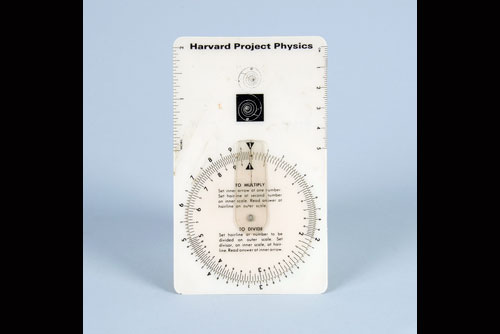

Calculator wheel

A calculator wheel to help with various mathematical and physical problems, part of Harvard’s “Project Physics.”

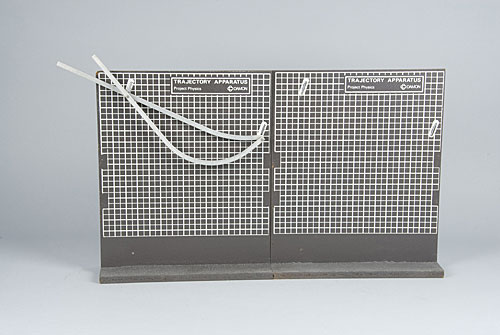

Trajectory apparatus

This is another instrument designed by Damon Engineering, in coordination with the ‘Project Physics” curricular work of Physics Professor Gerald Holton, California high school teacher F. James Rutherford, and Harvard Graduate School of Education Professor Fletcher G. Watson.

The ‘enemy’

The U.S. crisis in education in the 1950s was portrayed as a stark, existential contest with the “enemy,” the Soviet Union.

Satellite-tracking scope

Project Moonwatch satellite-tracking telescope, Micronta, c. 1957. From the tracking of Sputnik to the Apollo 13 landing, the triumph and tribulations of the American space program blurred the boundaries between scientific research, patriotism, and military technology.

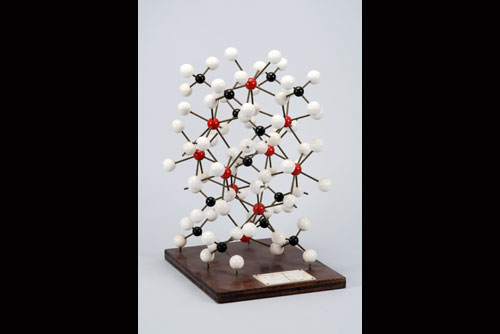

Scheelite

A complex, symmetrical mineral molecular model representing the substance scheelite (CaW04), made of plastic spheres and brass rods. It was constructed by a Harvard student from the Department of Geology and Geography in the spring of 1965.