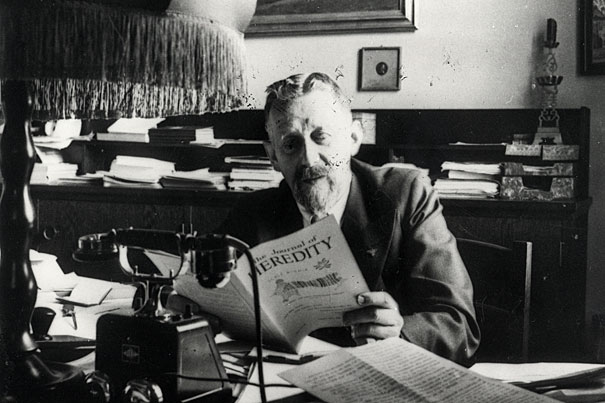

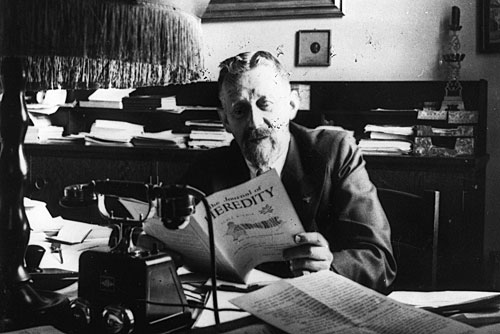

Eugen Fischer, director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Eugenics, and Human Heredity from 1927 to 1942, taught courses for SS doctors, served as a judge on Berlin’s Hereditary Health Court, and provided hundreds of opinions on the paternity and “racial purity” of individuals.

Evolution of ‘final solution’

Child victim of Nazi medical experiments recounts horrors

The table slab was cold and hard beneath 6-year-old Irene Hizme as doctors and nurses took measurements and blood samples. She didn’t know what was happening to her, and by the time it was all over, she wouldn’t care. She was found lying nearly comatose on the ground by a woman who brought her home to begin her recovery.

Though it’s routine for children to be examined by physicians, that was hardly the case here. Her doctor was Josef Mengele, the infamous Nazi who conducted cruel experiments on inmates at the Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II.

Hizme, who survived both her imprisonment and Mengele’s experiments, told her story to a rapt audience at Harvard Medical School’s Joseph Martin Conference Center in the New Research Building on April 14. Hizme was participating in a program to kick off the opening of an exhibit at Harvard Medical School’s Countway Library of Medicine, “Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race.”

The exhibit, created by the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in collaboration with a long list of institutional sponsors, addresses physicians’ roles in the evolution of what became the Holocaust through the early decades of the 1900s to the horror of its full execution during World War II.

The exhibit presents an eye-opening look at some of the lesser-known programs — many of which involved physicians — that established the Nazi philosophy of racial improvement and then implemented it through the 1930s. These programs began in 1933 with forced sterilization of the blind, deaf, alcoholics, physically deformed, and other groups judged inferior. In 1939, the murders began of thousands of children born with deformities, moving on to the killings of hundreds of thousands of adults institutionalized for mental illness and other causes. That program saw the development and use of gas chambers, later employed against Europe’s Jews and other groups in Nazi death camps.

When Hizme, who was born in Prague, arrived at Auschwitz, she remembered the stifling, stinking conditions in the cattle car she and others rode and how relieved everyone was when the doors opened at their destination and let in fresh air. The relief for the 6-year-old and others didn’t last long, as they were rousted from the car and sorted, a duty carried out by doctors, with some prisoners going to the camp and others to the gas chambers.

Because Mengele had an interest in twins for his heredity experiments, she and her brother were kept alive. She believes that she was experimented on while her brother was used as a control. She recalled X-rays and many injections whose contents she still doesn’t know, and of being sick in the camp hospital many times. During one of those times, all the patients were gassed, while she was saved by a nurse who hid her under her skirt.

“I was young, so I really did not understand what was going on,” Hizme said.

Julie Hock, New England regional director of the U.S. Holocaust Museum, said the organization has had many exhibits over the years, but this is the first that begins to answer the question on people’s minds as they try to grasp the enormity of what happened: How was this humanly possible?

Susan Bachrach, the exhibit’s curator, and Boston University Professor Michael Grodin, who has written about Holocaust doctors, laid out how the rediscovery of Gregor Mendel’s genetics experiments led to the growth of the global eugenics movement in the early 1900s. Eugenics organizations, seeking human perfection, were active in many countries, including Germany and the United States. In America, many states had forced-sterilization programs, backed by the Supreme Court, which in 1927 upheld Virginia’s such program for the “feebleminded.”

Grodin said physicians played not just a bit part, but a central role in both the eugenics philosophy and in its eventual translation into Nazi programs to “disinfect” society. Doctors had a much greater representation in the Nazi Party than average Germans and played key roles throughout.

“Physicians were not victims; they were perpetrators,” Grodin said. “Nothing was inevitable; choices were made.”

In his research, Grodin sought to determine why physicians who pledge to improve human life wound up joining with the Nazis instead. He said there were some traits that might explain some physician participation — such as a willingness to dehumanize patients, an ability to compartmentalize their own lives, and a feeling of omnipotence — but added there was no way of predicting who would wind up embracing Nazi activities, just as there was no way of predicting who would wind up protecting the persecuted, risking their own lives.

Grodin cautioned against thinking that the Holocaust was an isolated event, and exhibit organizers said the displays are intended to provide food for thought for some of today’s ethical questions. After all, Grodin said, black soldiers who liberated the prison camps were fighting in segregated companies, interracial marriage was outlawed in many states, and medical experiments in the United States have been repeatedly carried out against unwilling participants.

Grodin cited the Willowbrook experiments, in which hepatitis was given to mentally retarded children in New York for 14 years in the 1950s and 1960s, the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, carried out on unsuspecting black men between 1932 and 1972, and the injection of patients at the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital with live cancer cells in 1962.

Grodin said the Holocaust reached the scale it did because it was state-sponsored instead of just supported by individuals. Still, he said, it is instructive to understand the smaller steps that ultimately led to the Nazi death camps.

“I think we have to be very concerned when we take small steps,” Grodin said.

‘Deadly Medicine’

Eugen Fischer

Eugen Fischer reading Heredity Journal. Fischer, director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Eugenics, and Human Heredity from 1927 to 1942, authored a 1913 study of the racially mixed children of Dutch men and Hottentot women in German southwest Africa. Fischer opposed “racial mixing,” arguing that “Negro blood” was of “lesser value” and that mixing it with “white blood” would bring about the demise of European culture. After 1933, Fischer adapted his institute’s activities to serve Nazi anti-Semitic policies. He taught courses for SS doctors, served as a judge on Berlin’s Hereditary Health Court, and provided hundreds of opinions on the paternity and “racial purity” of individuals, including the Mischlinge offspring of Jewish and non-Jewish German couples. Credit: Archiv zur Geschichte der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Berlin-Dahlem

German Hygiene Museum

Nazi officials at the “The Miracle of Life” exhibition, German Hygiene Museum, Dresden, 1935. The new Nazi museum leadership asserted that societies resembled organisms that followed the lead of their brains. The most logical social structure was one that saw society as a collective unit, literally a body guided by a strong leader. Credit: National Archives and Records Administration

Racial classification

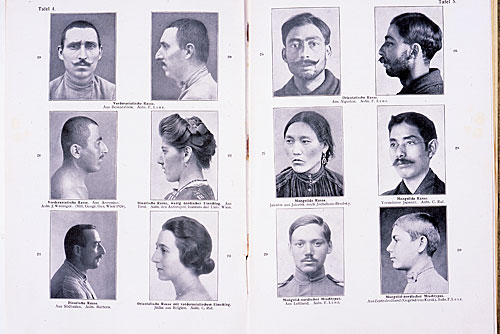

Head shots showing various racial types. Most Western anthropologists classified people into “races” based on physical traits such as head size and eye, hair, and skin color. This classification was developed by Eugen Fischer and published in the 1921 and 1923 editions of Foundations of Human Genetics and Racial Hygiene. Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

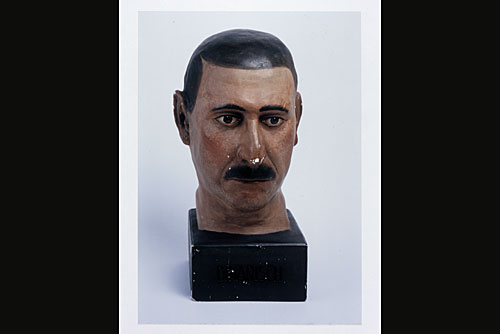

Dinaric

Heads of racial types, created by anthropologists from plaster molds of the faces of living subjects, were mass-produced in Nazi Germany for use in exhibitions and racial hygiene classes. This head portrays the “Dinaric” (Balkan) racial type. Credit: Blinden-Museum an der Johann-Agust-Zeune-Schule fur Blinde, Berlin

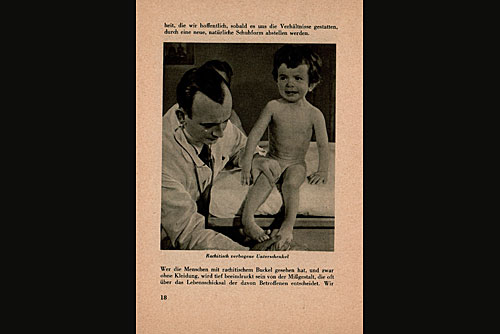

Enst Wentzler

Enst Wentzler treats a child with rickets. Wentzler’s Berlin pediatric clinic served many wealthy families and high-ranking Nazi officials. Although Wentzler developed methods to treat premature infants or children with severe birth defects, he supported ending the lives of the “incurably ill” and served as a primary coordinator of the pediatric “euthanasia” program, evaluating patient forms and ordering the killing of several thousand children. Credit: National Library of Medical Science, Bethesda, Md.