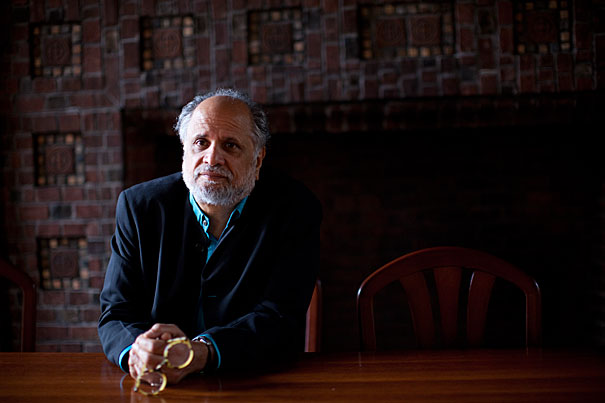

Homi Bhabha (above), director of the Humanities Center at Harvard, says that the $10 million gift to the center by Anand Mahindra ’77, M.B.A. ’81, “emphasizes the global reach of the humanities. The humanities are a global project.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard Humanities 2.0

Center gains lift in a gift of $10 million from a Harvard alumnus

Anand Mahindra, scion of one of India’s wealthiest industrial families, arrived at Harvard in the fall of 1973 as a teenager with dreams that went beyond business. He concentrated in film at the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies, graduated magna cum laude in 1977, and only later began a vocation outside the humanities.

Mahindra earned an M.B.A. at Harvard Business School in 1981, and now is vice chairman and managing director of the flagship company in his family’s Mahindra Group. But the confidence and perspective that he gained from studying film, literature, and the arts remained with him. Hence, he has given $10 million to the Humanities Center at Harvard, the largest gift of its kind in the University’s history.

In a PBS television interview last year, Mahindra said America’s greatest gift to the world is its tradition of liberal arts education — giving students a way to explore culture and history before getting down to the vocational business of graduate school. He called his “adventure in film” at Harvard the root of his sense of self. “Even today,” Mahindra told interviewer Charlie Rose, “my inner confidence is derived from just that.”

Mahindra’s gift will enable the Humanities Center to build on what it has already achieved, said center director Homi Bhabha, Harvard’s Anne F. Rothenberg Professor of the Humanities. That means enhanced collaborations between the humanities and other fields of knowledge at Harvard, and widening the reach of the humanities nationally and abroad.

Coming from India, the gift also “emphasizes the global reach of the humanities,” he said. “The humanities are a global project.”

The Humanities Center, said Bhabha, already has reached out to the social and natural sciences. “The humanities never sit still,” said the India-born scholar who has a doctorate in literature from Oxford University. “The humanities always busy themselves with the business of the world, and refuse to be contained.”

The gift will also allow the Humanities Center to sponsor more events, support more doctoral and postdoctoral students, help younger colleagues turn dissertations into books, and open up “larger circles of collegiality,” said Bhabha. (The center already collaborates with the Volkswagen Foundation in its postdoctoral fellowship program.)

The gift may also help Harvard bring the humanities into the arena of policymaking, he said, “where at this point the humanities have only a feeble voice.”

Bhabha added that Harvard is already strongly supporting humanities initiatives, particularly through the offices of President Drew Faust, University Provost Steven E. Hyman, and Faculty of Arts and Sciences Dean Michael D. Smith. (In the spring, Faust will name a faculty working group on the humanities, charged with, among other things, investigating the present role of humanistic studies in Harvard’s curriculum.)

The gift itself provides a reminder, said Bhabha, that India and South Asia have long traditions of accomplishment within the cosmopolitan realm of the humanities. It was never just a region defined by religion — Hinduism, Islam, or Christianity — but even today is a lively home to writers, performers, painters, and poets.

That was also true in the past, he said, including the ancient kings who filled their courts with thinkers from every religious tradition in the known world, and modern figures such as Mohandas Gandhi who were “internationalists before they were nationalists.”

Bhabha acknowledged that the world is accelerating into the digital age, but that the humanities will not be left behind. He suggested they will become more relevant than ever.

“Human history, human culture, human art, human learning gets transformed in unexpected ways,” said Bhabha. Film is going digital, books are being rendered in electrons on flat screens, and literature is now “part of the blogosphere.”

In this age of innovation, “the themes, values, and images” of culture are “continually being translated by different media,” he said. “This is just the kind of issue that the humanities always deal with. The humanities are most perceptive in thinking about complex moments of transition.”

During moments of fast cultural change, “the humanities make judgments and choices,” said Bhabha. “This is the moment for the humanities to find its platform.”

More immediately, and personally, the humanities have a role in an issue that interdisciplinary scholars at Harvard and elsewhere have lately taken a deep interest in: happiness.

“The humanities contribute in a profound way to our happiness,” said Bhabha. “They teach us the arts of interpretation. And it is through the arts of interpretation that we can turn information — which is in this point of time an endless barrage — into knowledge, and then turn knowledge into self-knowledge.”

The arts of interpretation are the humanities’ gift to students, as they once were at Harvard to the teenage Mahindra.

“Interpretation is not some dry hermeneutic exercise,” said Bhabha. “It contributes profoundly to the richness and happiness of our experience. It allows us to make the knowledge we have of the world outside ourselves into something deeply and intimately meaningful.”