(clockwise from top left) Thomas R. Cech, David H. Souter, Freeman A. Hrabowski III, Renée C. Fox, Thomas Nagel, Meryl Streep, Richard Serra, Susan Lindquist, David G. Nathan, and The Baroness Onora O’Neill of Bengarve.

Honorary degrees awarded

Ten will receive honorary degrees during Morning Exercises

Harvard will confer 10 honorary degrees today (May 27) during the Morning Exercises.

David H. Souter

Doctor of Laws

David H. Souter was an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court for 19 years before retiring in June 2009. Souter, who graduated from Harvard College in 1961 and Harvard Law School in 1966, will be the principal speaker at the Afternoon Exercises at this year’s Commencement.

David H. Souter was an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court for 19 years before retiring in June 2009. Souter, who graduated from Harvard College in 1961 and Harvard Law School in 1966, will be the principal speaker at the Afternoon Exercises at this year’s Commencement.

Harvard President Drew Faust hailed Souter’s “deep sense of independence and fairness” and “clear concern for the effects of the court’s decisions on the lives of real people” in making the Commencement speaker announcement. She said his “dedication, humility, and commitment to learning” should be an inspiration to anyone contemplating a career in public service.

Souter was also a Rhodes Scholar, earning an M.A. from Magdalen College in Oxford in 1963.

Nominated by President George H.W. Bush, Souter came to the court after spending many years at posts in the New Hampshire legal system. Born in Massachusetts, he moved to New Hampshire as a boy. After graduating from Harvard Law School, he began his legal career in private practice. In 1968, he was named assistant attorney general of New Hampshire. In 1971, he became deputy attorney general, and, in 1976, attorney general. He became a state Superior Court associate justice two years later and was appointed to the state Supreme Court as an associate justice in 1983. He became a judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit in 1990, shortly before his nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court.

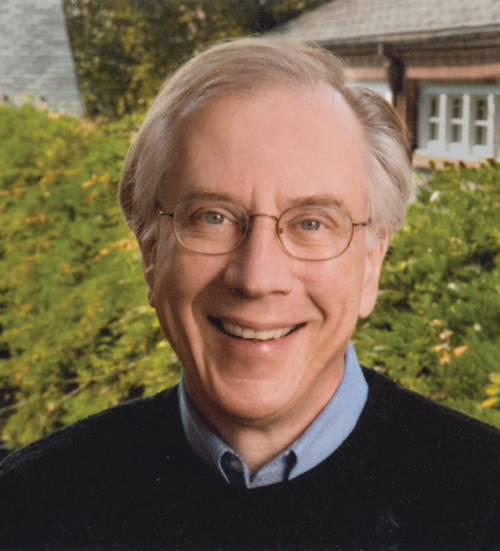

Thomas R. Cech

Doctor of Science

Thomas R. Cech, director of the Colorado Institute for Molecular Biotechnology at the University of Colorado, has made important contributions to understanding RNA, findings that won him the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1989.

Thomas R. Cech, director of the Colorado Institute for Molecular Biotechnology at the University of Colorado, has made important contributions to understanding RNA, findings that won him the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1989.

Cech was awarded the Nobel for revelations that RNA, ribonucleic acid, has functions beyond its role as a carrier of genetic information. In a single-celled organism, Tetrahymena thermophila, Cech discovered that RNA can also function as an enzyme, a function that had previously been thought to be the exclusive domain of proteins. These RNA enzymes are called ribozymes.

Cech grew up in Iowa and earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Grinnell College in 1970. He received a doctorate in chemistry from the University of California, Berkeley, and did postdoctoral research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He joined the University of Colorado faculty in 1978 and became a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator in 1988 and distinguished professor of chemistry and biochemistry in 1990.

In 2000, Cech became the president of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and led that organization until 2009, when he returned to the University of Colorado as director of the Colorado Institute for Molecular Biotechnology.

In addition to the Nobel Prize, Cech has won numerous awards and honors, including the Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award in 1988, the National Medal of Science in 1995, and the Heineken Prize of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences in 1988. In 1987, Cech was elected to the U.S. National Academy of Sciences and was awarded a lifetime professorship by the American Cancer Society.

Renée C. Fox

Doctor of Laws

Renée C. Fox’s studies in the sociology of medicine, medical ethics, medical research, and medical education have led her to Belgium, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, China, and the United States, and have resulted in nine books and numerous articles.

Renée C. Fox’s studies in the sociology of medicine, medical ethics, medical research, and medical education have led her to Belgium, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, China, and the United States, and have resulted in nine books and numerous articles.

Fox earned a doctorate in sociology from Harvard in 1954. She received a bachelor’s degree summa cum laude from Smith College. She joined the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania in 1969, where she is Annenberg Professor Emerita of the Social Sciences.

Before joining the University of Pennsylvania’s faculty, Fox was a member of the Columbia University Bureau of Applied Social Research. She taught for 12 years at Barnard College and then was a visiting lecturer for two years at Harvard’s Department of Social Relations. At Pennsylvania, she was a professor in the Sociology Department with joint secondary appointments in the Departments of Psychiatry and Medicine, and in the School of Nursing. She also held an interdisciplinary chair as the Annenberg Professor of the Social Sciences.

Her best-known books are “Experiment Perilous: Physicians and Patients Facing the Unknown,” “The Courage to Fail: A Social View of Organ Transplants and Dialysis,” “Spare Parts: Organ Replacement in American Society,” “The Sociology of Medicine: A Participant Observer’s View,” and “In the Belgian Chateau: The Spirit and Culture of a European Society in an Age of Change.” She is working on a book about her life as a sociologist.

Fox is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and of the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences. She is a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She has received a Radcliffe Graduate School Medal and a Centennial Medal from the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. She has won several teaching awards, holds nine honorary degrees, and in 2007 received the Lifetime Achievement Award of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities.

Freeman A. Hrabowski III

Doctor of Laws

Freeman A. Hrabowski III is committed to rigorous academic standards and challenging students to excel. The president of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), who chose to fund a championship chess team at the school instead of a football program, has built a career devoted to education and to helping minorities succeed in science, technology, engineering, and math.

Freeman A. Hrabowski III is committed to rigorous academic standards and challenging students to excel. The president of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), who chose to fund a championship chess team at the school instead of a football program, has built a career devoted to education and to helping minorities succeed in science, technology, engineering, and math.

In 1988 he co-founded the Meyerhoff Scholarship Program at UMBC with the goal of increasing the diversity of future leaders in science, technology, engineering, and related fields. Originally geared toward African-American males, the program has expanded to students of all races and both genders, and has been recognized by the National Science Foundation as a national model.

Called a “tireless academic cheerleader,” he was associate dean of graduate studies and associate professor of statistics and research at Alabama A&M University from 1976 to 1977. He was a professor of mathematics at Coppin State College in Baltimore for 10 years, and served as dean of arts and sciences from 1977 to 1981. He was the school’s vice president for academic affairs from 1981 to 1987. He went to the UMBC as vice provost in 1987, and was appointed president in 1993.

The son of teachers, Hrabowski was jailed for a week at age 12 after marching against school segregation in his home city of Birmingham, Ala. “The experience taught me that the more we expect of children, the more they can do,” he said in a 2008 interview with U.S. News & World Report, which named him one of America’s best leaders.

An early academic standout, he skipped two grades and graduated from high school at age 15. Four years later he graduated from Hampton Institute with the highest honors in mathematics. He received his master’s in mathematics in 1971 and his Ph.D. in higher education administration and educational statistics in 1975 from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

He is a member of several boards, including the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. He is the co-author of “Beating the Odds: Raising Academically Successful African American Males.” In 2009, Time magazine named Hrabowski one of America’s 10 best college presidents.

Susan Lindquist

Doctor of Science

Understanding how malformed proteins affect the human body, and how they are involved in evolution, is the realm of biologist Susan Lindquist, Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and professor of biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Understanding how malformed proteins affect the human body, and how they are involved in evolution, is the realm of biologist Susan Lindquist, Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator and professor of biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Lindquist, an authority on the complex molecular phenomenon called protein folding, explores how misfolded proteins play a role in diseases such as cancer, cystic fibrosis, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s. She uses yeast-based models of such protein-folded diseases to develop new approaches to therapy.

One area of Lindquist’s research examines the “chaperone” heat shock proteins that assist in protein folding and help to buffer genetic mutations. When such chaperone systems are overwhelmed, misfolding and disease states can result. The former director of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research also has explored how such misfolded proteins affect some evolutionary changes.

“One implication of our work is that the protein-folding problem isn’t always a problem,” notes Lindquist’s lab home page. “The very same types of misfoldings that cause dreadful diseases in some circumstances can have beneficial effects in others. The protein-folding problem is as ancient as life itself; it makes sense that evolution would occasionally, perhaps even often, use it to advantage.”

As a Radcliffe Fellow in 2007-08, Lindquist continued her investigations into the connections between genomics and medicine.

Lindquist received her undergraduate degree in microbiology from the University of Illinois in 1971. She received her Ph.D. in biology from Harvard University in 1976. In 1999 she was named the Albert D. Lasker Professor of Medical Sciences at the University of Chicago.

Her awards include the Dickson Prize in Medicine, the Centennial Medal of the Harvard University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the Otto-Warburg Prize, and the Genetics Society of America Medal. She is an associate member of the Broad Institute, a member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, and an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National Academy of Sciences. She is the co-founder of the Cambridge-based FoldRx Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Thomas Nagel

Doctor of Laws

American philosopher of the mind Thomas Nagel is known for “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” This rumination on the idea of consciousness — and the limits of science for explaining it — was published in the October 1974 issue of The Philosophical Review.

American philosopher of the mind Thomas Nagel is known for “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” This rumination on the idea of consciousness — and the limits of science for explaining it — was published in the October 1974 issue of The Philosophical Review.

The article articulates a central concern of Nagel, who said that humans instinctually want to make sense of the world, but adopting a unified, purely objective worldview can lead to error. In fact, relying on scientific objectivity alone leaves out some essential component of understanding ourselves.

Since 1980, Nagel has taught at New York University, where he is University Professor of Philosophy and Law. His other interests include political philosophy and ethics. He published his first philosophy paper in 1959 and his first book, “The Possibility of Altruism,” in 1970. Subsequent books include “Moral Questions” (1979), “What Does It All Mean?” (1987), “The Myth of Ownership: Taxes and Justice” (2002, with Liam Murphy), and the recent “Secular Philosophy and Religious Temperament” (2009), a book of essays.

Nagel was born in 1937 in Belgrade, in present-day Serbia, and as a young child moved to the United States. He earned a B.A. in 1958 from Cornell University, a B.Phil. from Corpus Christi College, Oxford, in 1960, and a Ph.D. from Harvard, where he was a student of philosopher John Rawls, in 1963.

He taught at the University of California, Berkeley, (1963-66) and at Princeton University (1966-80) and has lectured at Stanford, Oxford, Johns Hopkins, Harvard, and Yale universities. In 2008, Nagel received both the Rolf Schock Prize in Logic and Philosophy and the Balzan Prize in Moral Philosophy.

Nagel is a fellow of the American Academy of Sciences, a corresponding fellow of the British Academy, and a member of the American Philosophical Society. In 2008, he received an honorary D.Litt. from Oxford.

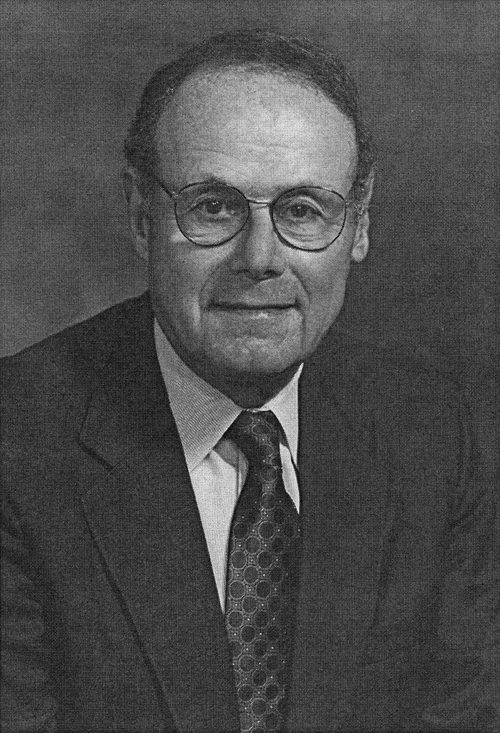

David G. Nathan

Doctor of Science

David G. Nathan, the Robert A. Stranahan Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, former physician-in-chief at Harvard-affiliated Children’s Hospital, and former president of the Harvard-affiliated Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, has had a career of discovery, teaching, and leadership that has not only pushed back the frontiers of knowledge of blood-based disorders but also fostered a generation of leaders who are guiding the field into the future.

David G. Nathan, the Robert A. Stranahan Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, former physician-in-chief at Harvard-affiliated Children’s Hospital, and former president of the Harvard-affiliated Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, has had a career of discovery, teaching, and leadership that has not only pushed back the frontiers of knowledge of blood-based disorders but also fostered a generation of leaders who are guiding the field into the future.

Nathan, who graduated from Harvard College in 1951 and from Harvard Medical School in 1955, is an authority on blood disorders. His discoveries have shed light on anemia and the hemoglobin disorder thalassemia. He won the National Medal of Science in 1990 “for his contributions to the understanding of the pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of thalassemia; for his contributions to the understanding of disorders of red cell permeability; for his contributions to the understanding of the regulation of erythropoiesis; and for his contributions to the training of a generation of hematologists and oncologists.”

Nathan has won many awards and honors over his career, including the John Howland Medal of the American Pediatric Society and the Kober Medal of the Association of American Physicians. He is one of three physicians to win both.

Nathan’s medical career began as an intern and senior resident at what was then the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. He spent two years as a clinical associate at the National Cancer Institute. From 1959 to 1966, he was a hematologist at Brigham Hospital, and then became chief of the Division of Hematology and Oncology at Children’s Hospital and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. In 1985, he was physician-in-chief at Children’s Hospital, a position he held until 1995, when he was named president of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. He served as Dana-Farber’s president until 2000.

He is the author of “Hematology of Infancy and Childhood,” which is the leading text in the field.

The Baroness Onora O’Neill of Bengarve

Doctor of Laws

Scholar and politician Onora O’Neill, Baroness O’Neill of Bengarve, studied philosophy, psychology, and physiology at Oxford University before earning her philosophy doctorate at Harvard in 1969.

Her mentor and dissertation adviser was American philosopher John Rawls, the one-time James Bryant Conant University Professor at Harvard whose signature work, “A Theory of Justice” is still a primary text in political philosophy.

A native of Northern Ireland, O’Neill has written widely and influentially on political philosophy and ethics, as well as on international justice, bioethics, media ethics, and the philosophy of Emmanuel Kant. Her work concerns issues of trust, consent, and respect for autonomy, in particular in the context of complex medical decision-making.

A veteran instructor at universities in the United Kingdom and the United States, she teaches philosophy at the University of Cambridge, where she was principal at Newnham College from 1992 to 2006.

O’Neill is the author of seven books and co-author of an eighth. Her works include “Acting on Principle” (1975), “Towards Justice and Virtue” (1996), “Bounds of Justice” (2000), and “Autonomy and Trust in Bioethics” (2001), the last being her Gifford Lectures in book form. (The prestigious Gifford Lectures, a tradition at Scottish universities, are designed to explore the idea of “natural theology,” that is, theology supported by science.)

O’Neill, a life peer, is a “crossbench” (nonparty) member of the British House of Lords. She has served on committees concerning stem cell research, genomic medicine, and nanotechnology and food.

O’Neill’s advisory work reflects her academic interests. In the United Kingdom, she has been a member of the Animal Procedures Committee, the Human Genetics Advisory Commission, and the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, which she chairs.

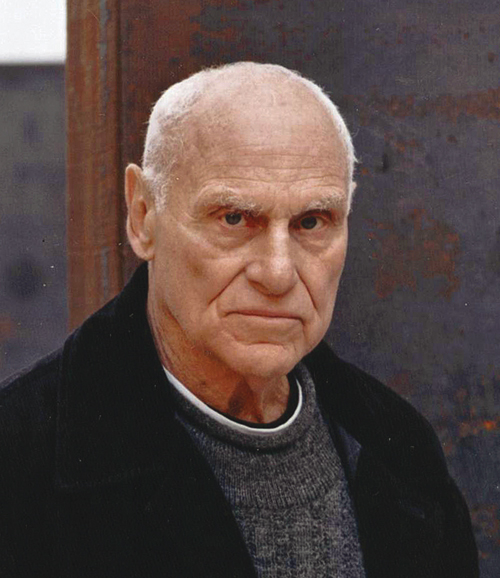

Richard Serra

Doctor of Arts

Minimalist sculptor and experimental video artist Richard Serra is famous for his monumental works in steel — a favorite medium — and for his experimental films, beginning with “Hand Catching Lead” in 1968. He is associated with the process art movement of the mid-1960s. It celebrates the serendipity of art (the drip painting of Jackson Pollock, for instance) as well as the process of making art (rather than the art itself).

Minimalist sculptor and experimental video artist Richard Serra is famous for his monumental works in steel — a favorite medium — and for his experimental films, beginning with “Hand Catching Lead” in 1968. He is associated with the process art movement of the mid-1960s. It celebrates the serendipity of art (the drip painting of Jackson Pollock, for instance) as well as the process of making art (rather than the art itself).

His first sculptures in the 1960s were made out of nontraditional materials such as fiberglass, neon, and rubber. But he soon graduated to his lifelong fascination with metals.

Born in 1939, Serra worked at steel mills to support himself while studying English literature at the University of California, Berkeley, and then at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he received a bachelor’s degree. From 1961 to 1964, Serra studied painting at Yale University, earning both a B.F.A. and an M.F.A.

From 1968 to 1970, he executed a series of “splash pieces” in which molten lead was splashed against walls. Serra moved to “prop pieces,” metal sculptures held together solely by balance and the force of gravity. In 1970, Serra began experimenting with large-scale sculptures that played off urban landscapes. Many were made of spirals and curving lines — counterpoints to the right angles that dominate city skylines.

He is best known for his looming minimalist constructions made from rolls of Cor-Ten steel. They were once dismissed as artifacts from an arrogant art world. Serra’s 120-foot-long Tilted Arc, installed in Manhattan’s Federal Plaza in 1981, was dismantled eight years later. But in 2007, The New York Times called Serra “a titan of sculpture, one of the last great modernists.” That year, four massive sculptures with the same whimsical curves were the centerpieces of a Serra retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Meryl Streep

Doctor of Arts

Academy Award-winning actress Meryl Streep has won fans around the world and the acting industry’s highest awards for her versatility, her ability to master accents and personas, and her ease with both dramatic and comedic roles.

Academy Award-winning actress Meryl Streep has won fans around the world and the acting industry’s highest awards for her versatility, her ability to master accents and personas, and her ease with both dramatic and comedic roles.

Considered one of the country’s greatest living actresses, Streep has been nominated 16 times for an Oscar, winning two, and 25 times for a Golden Globe, winning seven. She is the most nominated performer for either award.

Born in New Jersey in 1949, Streep’s initial artistic interest was opera, but she eventually gravitated toward theater, graduating with a bachelor’s degree in drama from Vassar College in 1971. She earned an M.F.A. from the Yale School of Drama in 1975.

Her early career involved the New York stage and included work with the New York Shakespeare Festival, as well as on Broadway. In 1978 she won an Emmy Award for her role in the television miniseries “Holocaust.”

Streep’s movie career blossomed with her role in the 1978 film “The Deer Hunter.” She received her first Academy Award nomination and has worked steadily in films since.

Two years later she won the Academy Award for best supporting actress for her role as a struggling mother in “Kramer vs. Kramer,” and won for best actress in 1983 for her portrayal of a tormented Holocaust survivor in “Sophie’s Choice.”

Streep’s other films include “The French Lieutenant’s Woman,” “Out of Africa,” “Silkwood,” “The River Wild,” “Adaptation,” “The Hours,” “The Devil Wears Prada,” and “Julie and Julia.”

Streep also is an environmental health activist. In 1989 she helped to found Mothers and Others, a consumer group advocating sustainable agriculture and increased pesticide regulations.

Among her many honors are a Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French government and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Film Institute.

— Compiled by Corydon Ireland, Alvin Powell, and Colleen Walsh