Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

What makes a life significant?

Exploring a robust question from William James

It is somehow comforting to know that one of the greatest minds of the past 100 years had a hard time making up his own mind.

William James, the oldest child in a celebrated American family and a pioneer in psychology and philosophy, was apparently a famous ditherer. “He’s just like a blob of mercury,” his sister Alice wrote. “You cannot put a mental finger upon him.”

Better than that, perhaps, James was a man of restless intelligence. While teaching at Harvard, he explored medicine, the mind, religion, and all the big questions that still beset people.

One of those questions was: “What makes a life significant?” — the title of a lecture James delivered at Harvard in 1900. (The answer, in sum, was to be awake to the significance of other people, and to escape that “great cloud bank of ancestral blindness” that leads to intolerance and cruelty.)

The same question was also the title of a panel on Monday (April 26), which celebrated James’ life and marked the centennial year of his death.

James Kloppenberg, a 40-year James scholar and Harvard’s Charles Warren Professor of American History, moderated the panel, and began with a question of his own: What relationship does James’ thought have to “our own cultural moment?”

Panelists Louis Menand, Sissela Bok, and Cornel West arrived at variations on the same answer: that James lives on into the 21st century, still a formative, formidable mind.

Menand, Harvard’s Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of English, said James was the equivalent of today’s public intellectual. He still offers a lesson to the modern world, said Menand: Beware of training and revering only specialists. James, after all, was not trained in anything he excelled in, and his schooling was as scattershot as it was fervent.

Bok, a philosopher who is Senior Visiting Fellow at the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies, said one of James’ ideas, to harness the energy of making war to the pursuit of making peace, would find purchase today. “He would surely be encouraged,” she said, at the vitality of doing public service, both inside and outside the university.

It is worth noting too that James’ “non-militarism” was at odds with the tenor of his own time, said Bok, and James “agonized over the increasingly aggressive role his country was taking” in the world.

And in another modern echo, she said, James worried that peace-loving men carried no weight equivalent to the warriors of the day.

In answer to his own doubts, James wrote “The Moral Equivalent of War,” a 1906 essay in which he proposed harnessing “manly” virtues to the cause of peace. “The martial type of character,” he wrote, “can be bred without war.”

He had a similar thought in “What Makes a Life Significant?” inspired by a train ride back from the Assembly Grounds in Chautauqua, N.Y. This “Sabbatical city” of sobriety, peace, and order, this “human drama without a villain or a pang,” James wrote, made him suddenly long “for something primordial and savage, even though it were as bad as an Armenian massacre.”

But if humans yearn for “everlasting battle” or visions of “human nature strained to its uttermost and on the rack,” he mused, why reach for war? Why not satisfy the same urges with hard labor — with pick, ax, scythe, and shovel. Such work, James wrote, reveals “the great fields of heroism lying around me.”

West, a former Harvard scholar who is the Class of 1943 University Professor at Princeton, said James had a sense of what the modern world needs now: “non-market values like love, empathy, benevolence, and sacrifice for others.”

He also had a sense that greatness could be something “different than success,” said West. “William James,” he wished out loud, “speak to us in 2010.”

James might bring another lesson forward into the 21st century: Leave your mind free, open, and skeptical.

It stood him in good stead that James lacked a systematic education, said Menand, author of “The Metaphysical Club,” a 2001 primer on pragmatism and other intellectual currents in James’ post-Civil War America.

Menand outlined the hopscotch schooling of James, whose father moved the family from place to place — back and forth to Europe — settling sometimes for only months in one place. By age 13, James had already attended 10 schools.

By 1861, James was enrolled at the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard, where he quickly jumped from engineering to anatomy to natural history and finally to medicine. A medical degree from Harvard in 1869 was the only credential James ever earned, and it was one he never used. He went on to do pioneering work in psychology and then philosophy. In the end, said Menand, James remained “a restless spirit.”

Through it all, James had a capacious, welcoming intelligence, said Kloppenberg.

The philosopher’s summer home in New Hampshire had nine doors, and “they all opened out,” he said, “consistent with James’ approach to the world.”

Those open doors invited in the big questions.

The meaning of life, said Bok, “is a question people keep asking.”

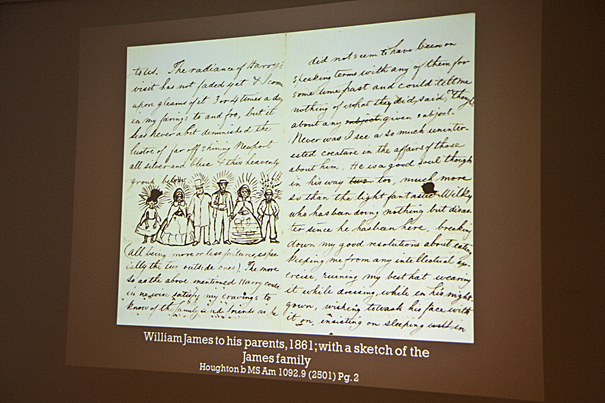

Celebrating William James

In a continuing James celebration this year, Harvard’s Houghton Library will house “Life is in the Transitions: William James, 1842-1910,” an exhibit of sketches, manuscripts, lecture notes, and letters, from Aug. 16 to Dec. 23. Houghton will host the final day of an Aug. 13-16 conference on James, “In the Footsteps of William James: A Symposium on the Legacy — and the Ongoing Uses — of James’s Work.” It’s co-sponsored by the William James Society and the Chocorua (N.H.) Community Association. (For more information, visit the William James Society Web site.)