Courtesy of HGSD

Boulders that bowl over

Exhibit showcases the place of rocks in the landscape and in art

Some rocks — as small as pebbles or as big as houses — are called “erratics,” since they were scattered over continents thousands of years ago by receding glaciers or rafts of ice. They look different than the native rock they come to rest on, and so they seem random and strange.

Those same qualities, over time, were turned to artistic purposes. Landscape painters of the 19th century used erratics to illustrate the strange majesty of nature. By 1857, when surveys began for what would become Central Park in Manhattan, erratics already on the site were incorporated into the design.

The science of geology — erratics and all — was a required subject in the nation’s first formal training program in landscape architecture, started at Harvard in 1900.

“New Englanders hated a boulder. They blew them up,” declared Harvard geologist Nathanial Slater in a lecture that year. “But the modern landscape architect does not do this. In general, we are to appreciate rock surfaces.”

That appreciation has taken some strange turns, from modest public fountains to faux cliffs to monumental fiberglass “rocks” lit from within. Many examples are on view at “Erratics: A Genealogy of Rock Landscape,” an exhibit at the Harvard Graduate School of Design’s (GSD) Gund Hall through May 12.

You get a sense of the past from the cases of drawings, photos, manuscripts, and rock specimens on display, all from Harvard collections. Included are recent offerings such as Harvey Fite’s “Opus 40” (1935-76); Michael Heizer’s spooky pile “Adjacent, Against, Upon” (1976); and James Pierce’s long, winding “Stone Serpent” (1979).

The exhibit’s extensive wall display of photos, diagrams, plans, and text provides a sense of the present as well as the future. Rock and other landscape elements, it seems, can be playful and plastic.

One section, “Erratics in Practice,“ looks at projects by GSD faculty and affiliated practitioners. “The title simply means built projects that use rocks or the form of erratic boulders as a central element,” said exhibit curator Jane Hutton, a GSD lecturer in landscape architecture.

Of immediate interest is the Tanner Fountain in front of the Science Center, a 1988 installation comprising 159 erratics, each around 4 feet wide, gathered from western Massachusetts. At dusk, it is a “cool white mass” that reflects light, the notes say, and after a rain “the center of the fountain glows like a warm cloud.”

“Stock-Pile” (2009) is a more recent Harvard addition to the tradition of rock in landscape architecture. Conical piles of stone, aggregate, sand, and soil — designed and installed in seven days — are “poised to subside,” the notes say. A year after the installation, the points have softened.

Most of the examples, though, point up rock’s near permanence. An erratic is displayed in a spare open house in China; tall volcanic rocks loom like giant tombstones in California; a walkway of basalt is set into an ancient streambed in the United Kingdom.

On fullest display is the work of Canadian landscape architect Claude Cormier, a 1994 GSD graduate. His whimsical work includes explicit use of rocks. “Sugar Beach/Jarvis Slip,” an urban beach being built on Toronto’s industrial waterfront, plays off a nearby sugar factory. A large erratic will be candy-striped in red and white.

A short essay on Cormier appears on one wall, written by the chair of GSD’s department of landscape architecture, Charles Waldheim, the John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture. “In an era when the discipline of landscape architecture has shifted its attention away from a concern with the visual in favor of landscape’s operational potentials,” he writes, “Cormier’s work offers a counterproposal: that landscape is itself historically inseparable from questions of visual perception.”

Other work by Cormier takes our perception of landscape a step further, creating works that mimic the real thing. “Lipstick Forest” (1999-2002) is a forest of large artificial trees — glossy and pink — in Montreal’s Convention Center.

“Blue Stick Garden” (2000) used scans of blue poppies to create a bed of blue sticks that are now on permanent display in Montreal, “not as a contemporary installation in a garden,” Cormier’s Web site says, “but a garden itself.”

Using rocks in landscape architecture has created whimsy too, as in the Nishi Harima Science Garden City in Japan (1994). Monumental fiberglass rocks there “glow like giant lanterns,” according to the exhibit card.

The “Roof Garden” (2005) at the Museum of Modern Art is a rock garden with few real rocks. Hollow plastic shapes of white and black, eerily uniform, are bolted to runners and set off by beds of crushed glass, shredded tires, and white stone.

Perhaps the future will echo Waldheim’s view of Cormier’s creations as “constant preoccupation with games of visual perception.”

‘Erratics: A Genealogy of Rock Landscape’ at Gund Hall

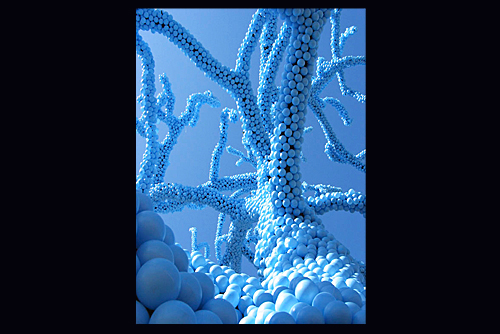

Electric blue

While looking like something biological — DNA or coral, even — this is actually artificial tree branches stretching into an equally blue sky. Once a diseased tree in Napa Valley, Cormier gave it new life — with 75,000 Christmas balls.

Lipstick forest

Artist Claude Cormier avoided using live plants, which he said he would fight to keep alive against the unforgiving local climate. Here, 52 concrete trees, painted lipstick-pink to celebrate the city’s flourishing cosmetic industry, are not your average houseplant.

My blue heaven

Created in 2000 for the inaugural season of the Métis International Garden Festival in Quebec, one of Cormier’s inspirations was the Himalayan blue poppy, which was painstakingly adapted to the region’s microclimate. Here, folks stroll through the reeds. A real garden, indeed.

D’Youville

Once the site of Canada’s Parliament, D’Youville’s sidewalks have been overlaid with wood, concrete, granite, and limestone, and jet between access points for the city museum, offices, restaurants, and residences on adjacent street facades.