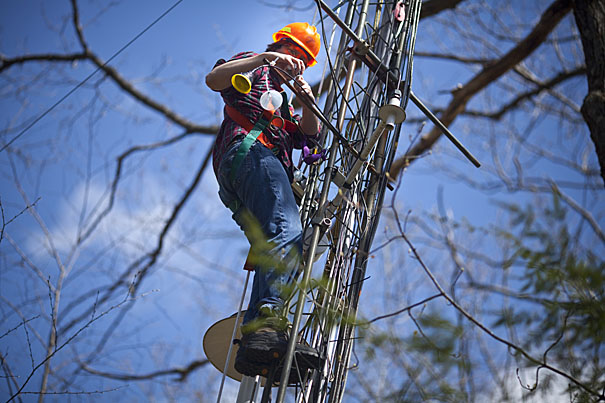

Harvard University research technician Josh McLaren works on a tower collecting environmental data at the Harvard Forest in Petersham, Mass.

Justin Ide/Harvard Staff Photographer

Battling climate change on all fronts

Harvard works to record, understand, and counter global shifts

The next time the Arctic’s mud season rolls around, Harvard scientists will be there, testing the air to record what the ground is releasing, searching for evidence of a climate change wild card that could spring a nasty worldwide surprise.

The wild card consists of methane — a powerful greenhouse gas — and carbon dioxide, perhaps the best-known climate-changer. The gases would be released, possibly in enormous quantities, by rotting organic material that for centuries was inert, frozen year-round in the subterranean permafrost.

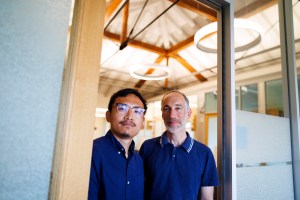

When it comes to climate change, Jim Anderson is stalking surprises. Harvard’s Weld Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry, Anderson has turned his lab’s focus toward the complex Earth-ice-atmosphere interactions of climate change that remain poorly understood despite the efforts of thousands of scientists worldwide.

To find out what’s going on in the Arctic, Anderson is outfitting a recently developed, robotic, fuel-efficient plane with a new instrument created in his lab by research associates Mark Witinski and David Sayres. Next spring, they plan to fly it remotely at low altitudes over the Arctic, sniffing away and seeing what gases are in the air over these melting regions, and in what quantities. The results will inform not only our understanding of the planetary forces at work, but also will influence estimates of the changes going on around us and our responses to them.

From pole to pole

Anderson isn’t the only one working on climate change at Harvard. In fact, he’s not even the only one flying a gas-sniffing plane to better understand the atmosphere. Colleague Steven Wofsy, Rotch Professor of Atmospheric and Environmental Science, is flying another from pole to pole to reveal the atmosphere’s makeup in more detail. Wofsy has been working on climate change for years. One of his experimental towers has been standing among the trees in the 3,000-acre Harvard Forest in Petersham for nearly two decades, providing a mountain of data on temperature, atmospheric water vapor, and carbon dioxide flow from the atmosphere to the trees. The forest is one of the oldest and most extensively studied on the continent.

Climate change is one of the most complex and pressing problems of the age, and faculty members across the University are bringing the tools of their disciplines to bear on its many facets.

Atmospheric and Earth scientists are examining the global-scale processes involved, pushing back the frontiers of knowledge on how the planet functions. Biologists are examining feedback concerning life, cataloging tropical trees’ growth to assess their capacity to store excess carbon, and even tracking changes at venerable Walden Pond, where Harvard graduate Henry David Thoreau spent two years in the 1840s living simply, albeit surrounded by somewhat different plant life.

Climate change, of course, is not just a scientific problem. Caused by human industry and exploitation of the natural world, its solutions are entwined in everyone’s daily activities and in the larger values that regulate how people live. As such, climate change touches governments that struggle to divine effective, politically possible solutions; it touches businesses that ponder their responsibilities beyond making a product, providing a service, and turning a profit; it affects health and medicine, as physicians and public health officials face the potential for shifting disease patterns and changes in drinking water availability; it affects those who conceive and design structures and plan cities.

Harvard’s faculty members are addressing these problems and many more. Government, business, public health, design, religion, and even literature are represented.

“Climate change is a global problem and one of the great challenges of our time,” said Harvard President Drew Faust. “Harvard’s great strength lies not just in the depth of its scholarship, but also in the breadth of the expertise found across our campus. Our faculty members are deeply engaged in this issue, helping us to better understand the complexities of our natural environment, the forces driving climate change, and the ways in which we can move toward a more sustainable future.”

Spanning the spectrum

Harvard’s climate-change efforts span the spectrum, from sober academic teaching to environment-themed cartoon contests, and the campus fairly buzzes with climate change-related activity. Research and teaching on the subject are augmented by a host of centers, programs, and student groups. Lectures abound and draw not just prominent authorities from around the world, but also capacity crowds eager to better understand the planet and others’ points of view.

The Harvard University Center for the Environment (HUCE), for example, sponsors a long-running series examining a key issue driving climate change: the energy used to power diverse activities. HUCE’s “Future of Energy” lecture series has hosted oil company executives, government officials, and proponents of alternative energy, enriching the climate change discussion through diverse points of view.

“There are so many climate-related events that it’s hard to get through the week and get my work done,” said Daniel Schrag, Sturgis Hooper Professor of Geology, professor of environmental science and engineering, and HUCE director.

As the major University-wide center for environmental issues, HUCE provides a coordinating, collaborative clearinghouse where researchers in far-flung fields can gather and discuss climate change. Among its many activities, the center provides a home for fellows researching environmental issues, fosters a community of doctoral students interested in energy and the environment through a graduate consortium, and provides seed grants to spur early-stage research.

The center also promotes less-formal discussions between faculty members working on environment-related issues, through regular breakfasts and dinner discussions. Faculty members working on climate science attend weekly ClimaTea talks with graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, fostering a collegial atmosphere and an exchange of ideas. Several other Schools also have their own centers, programs, classes, and courses of study on the environment, climate change, and related issues.

Grace Brown, a junior environmental science and public policy concentrator, said her classes in economics, policy, and science provide a broad background for understanding these complex issues. During her time at Harvard, Brown has designed a study on organic foods at Harvard Dining Services and works with the Harvard College Environmental Action Committee. She intends to continue working on environmental issues and plans to intern this summer with the U.S. Department of Energy. Eventually, she hopes to attend law school and work in government.

“I came to Harvard as a crunchy environmentalist, wanting to save the forests,” Brown said. “I understand now how climate change impacts not just the forests, but our lives, my life. It makes climate change bigger and scarier when you understand its impact on people. It’s not just saving trees.”

The University itself has made becoming a sustainable institution a high priority in recent years, taking an array of steps to lessen its impact on the environment, from switching to energy-efficient lighting to purchasing renewable energy to running shuttle buses on biodiesel. (See the related story on Harvard’s internal efforts.)

Unraveling complexity

In many ways, the problems of climate change have highlighted how little we know about Earth. Climate change affects the most fundamental natural processes, some of which are well understood, and some not.

Just as important as understanding the processes is discerning the ways they affect each other. Even slightly warmed ocean waters affect the tongues of Greenland’s glaciers sticking into the sea, causing earth-shaking calving that can be detected at Harvard; drinking water for millions is affected by melting Asian glaciers, being studied by Peter Huybers, assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences, and Armin Schwartzman, assistant professor of biostatistics at the Harvard School of Public Health. Researchers such as Schrag study the dramatic swings of past climates, including such extremes as “snowball Earth,” for clues to processes and feedbacks that affect the planet’s behavior and look to the future as well, providing a foundation for climate change mitigation efforts, such as carbon capture and sequestration.

Global political leaders look to the scientific community to inform their actions. But, given the pressing nature of the climate problem, leaders can’t wait to act until all the answers are known. Harvard’s authorities on governance are examining the knotty problem of how to forge a planetwide consensus on what actions are needed. At the Harvard Kennedy School, faculty members such as Jeffrey Frankel, Harpel Professor of Capital Formation and Growth, and Robert Stavins, the Pratt Professor of Business and Government who heads the Harvard Project on International Climate Change Agreements, are working to identify and advance policy options based on sound scientific and economic reasoning.

In the wake of December’s failed Copenhagen climate summit, Stavins’ project is examining options for moving forward. It plans to bring together authorities to discuss alternatives with an eye toward the next chance at forging international consensus, a December meeting planned for Cancun, Mexico. The group’s activities have already resulted in two books, and Stavins expects upcoming discussions to be published and available to representatives at the Cancun meetings.

The spiritual side

Outside scientific and policy circles, Harvard’s specialists in the humanities are addressing climate change in their own way. For instance, James Engell, chair of the English and American Literature and Language Department, examines the intersection of the environment and literature, and professor of history Emma Rothschild has written on the decline of the auto industry and the need for increased use of public transportation and other alternatives.

Donald Swearer, director of the Center for the Study of World Religions, said it’s important for religion and the humanities to play a role because they get to the heart of what makes us human, what our values are, and how we define our relationship with the natural world. In a recent conversation, Swearer talked about “enoughness,” and how people should live thoughtfully in concert with their lifestyle’s impact on the natural world.

Swearer, who edited a recent book called “Ecology and the Environment: Perspectives from the Humanities,” said climate change stems from millions of choices made by individuals over many years. Once the science is known and the policies passed, success will still depend on influencing individual behavior.

Though society’s inertia on these issues may seem impossible to overcome, Swearer pointed out that we got here through many changes over the years, so change can lead us to a new future.

“What we need to be able to do is create a positive vision of what those changes can be,” Swearer said.