Harvard Forest:

3,500 thickly-wooded acres with global impact

Harvard may be rooted in Cambridge, but it has a lot more roots in the small north-central Massachusetts town of Petersham.

That’s where you’ll find the woods, streams, and fields of the Harvard

Forest, a 3,500-acre research and teaching facility that’s been part of

the University for more than a century. Having been closely monitored

since 1907 — and with a provenance dating to a Colonial farm

established in the mid 1700s — the history of this tract is likely

better-documented than that of any other forest in the United States.

New England’s forests have a centuries-long history of destruction

and resurrection, with a landscape that has veered from thickly wooded

in the 18th century to mostly farmland in the 19th century and back to

substantially wooded today. The much-researched Harvard Forest helps

scientists apply the lessons of the region’s forest history to the

environmental challenges faced by forests today.

“Overall, this forest offers a very positive message for New England

about the resilience of our forests,” says David R. Foster, the

forest’s director and a senior lecturer on biology in the Faculty of

Arts and Sciences (FAS). “The Harvard Forest can teach us much about

the history and diversity of natural landscapes.”

Since becoming director of the forest in 1990, Foster has worked

assiduously to knit together what had been isolated islands of

conservation land in north-central Massachusetts into a more coherent

block, the better to support research and maintain native flora and

fauna. Today, the map of this area at the head of the Quabbin Reservoir

— the body of water that supplies much of metropolitan Boston’s

drinking water — is a patchwork of land owned not only by Harvard but

also by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the Trustees of

Reservations, MassAudubon, and other conservation-oriented organizations.

Since 2005, Foster and colleagues have led an initiative called

“Wildlands and Woodlands: A Vision for the Forests of Massachusetts,”

endeavoring to protect 1.5 million new acres of Bay State forestland.

When combined with the existing 1 million acres of protected land in

the commonwealth, the cumulative acreage would total roughly half the

area of Massachusetts.

“We’ve already seen Massachusetts emerge as a leader in reclaiming

the Northeast’s fragmented landscape,” Foster says. “We hope ‘Wildlands

and Woodlands’ will spur new conservation finance tools to safeguard

the economic, ecosystem, and quality-of-life benefits of forests.”

The Harvard Forest’s 45 permanent employees — ranging from

ecologists to a sawyer who runs a Depression-era sawmill and cuts wood

to heat the forest’s buildings — are continually supplemented by a

steady stream of visiting scientists from New England and beyond. At

any given time, upward of 100 scientists — many from Harvard but most

from elsewhere — may be conducting research. The researchers are drawn

to Petersham, population 1,180, by these woods, wetlands, and Harvard

Pond. Collectively, the scientists form the Harvard Forest Long Term

Ecological Research Program, part of the largest ecology research

effort funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

It’s not just professional scientists at Harvard Forest, which plays

host each summer to some 25 undergraduate researchers, most of whom

hail from other universities. A dozen of these junior scientists are

supported for 12 weeks apiece by NSF’s Research Experience for

Undergraduates (REU) program. The Harvard Forest’s REU program, in

operation continuously since 1986, is not only one of the

longest-running nationwide but also among the most extensive in the

biological sciences at a single site.

With so many scientists around, the forest’s facilities are abuzz with research projects.

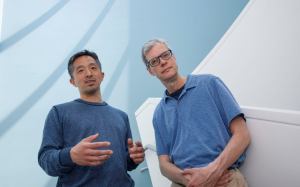

On a recent day, visiting scientists Wyatt Oswald of Emerson College,

and Matts Lindbladh of Sweden, were in a lab sampling from an 8-meter

core of mud extracted from the bottom of Little Willey Pond in

Strafford, N.H. This core, representing some 12,000 to 13,000 years of

pond deposition, will be studied for pollen, minerals, and organic

matter to reconstruct New England’s forest history, providing evidence

of climate change, human activity, and disturbances such as fires or

hurricanes.

Out in the woods, Emery Boose, the forest’s information manager,

pointed out another research project, launched this spring. A tract of

red pine planted in the 1930s — and starting to suffer natural decline

owing to its age — has been clear-cut and outfitted with two different

types of enclosures to exclude deer and moose. The project will study

the effects of grazing by both species on forest regrowth.

Deeper into the forest, staff scientist Julian Hadley was manning

air-monitoring equipment mounted atop a 70-foot metal structure known

as Hemlock Tower. These experiments, intended to measure and track the

output of water and carbon dioxide by the surrounding grove of

200-year-old conifers, illuminate the important role of forests in

maintaining the Earth’s carbon cycle.

Nearby is an apparatus placed by a Bridgewater State College

professor who makes snowfall predictions and uses cameras to monitor

from afar the accumulation of snow in the forest. Other measurements

are being taken at streams that feed into the Quabbin, so scientists

can examine how precipitation and transpiration affect water flow and

water chemistry.

Researchers with the University of Massachusetts have outfitted 25

area moose with GPS collars to track the gangly woodland dwellers,

whose numbers have grown steadily in northern Massachusetts. The

Harvard Forest is even seeing signs of resettlement by bears, which not

long ago were found only in the most remote areas of far northern New

England.

With all this data gathering, the Harvard Forest is intensively

wired to relay data back to scientists in Cambridge or even thousands

of miles away. Backed by ample computing power, automated equipment

gathers and archives climate data five times a second, making it

available internationally in real time.

With so many people monitoring his woods from afar, one of Foster’s

current priorities is making the Harvard Forest wireless, eliminating

the trouble-prone wiring running beneath dirt paths throughout the

woods. Rodents and other critters, it seems, like to gnaw on the wires.