HMS introduces wilderness fellowship

MGH-funded position is first offered east of the Mississippi

Snake bites, lightning strikes, hypothermia, tick bites, and avalanche injuries are not mishaps you ordinarily associate with Harvard Medical School (HMS), or with life in Boston.

But they are the grist of wilderness medicine, a subset of emergency practice that focuses on outdoor settings an hour or more away from definitive medical care. The specialty is getting increasing attention worldwide as people take to the outdoors for work or recreation.

Starting July 1, HMS will have its first Wilderness Medicine Fellow, funded through Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). It’s the first such fellowship offered east of the Mississippi River.

Five years ago, Stanford University offered the first wilderness medicine fellowship, quickly followed by the University of Utah.

Related courses are available at a few U.S. medical schools, including Johns Hopkins and Cornell, and the American College of Emergency Physicians sponsors a “section” (interest group) in wilderness medicine.

Harvard’s first fellow is Tracy Cushing, a full-time emergency medicine physician at Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Mass. She took her medical degree in 2002 at New York University, and was a Harvard-affiliated emergency medicine resident until last year. On June 5, Cushing will receive a master’s degree from the Harvard School of Public Health.

For her fellowship year, she will continue to provide emergency clinical care in an urban setting — but rural adventure also awaits.

In June, Cushing will be on hand as an “event physician” during a multi-day adventure race in Montana, where 60 teams of elite athletes will hike, bike, trek, paddle, and climb their way through a grueling 500-mile course.

“Some of them don’t sleep for 24 or 48 hours,” said Cushing, herself a mountain biker, climber, and solo backpacker. So she’ll do some research into the relationship between sleep deprivation and sports injuries.

In July, Cushing will attend a professional conference in Snowmass, Colo., commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Utah-based Wilderness Medical Society, the largest U.S. education group for outdoor medicine.

In November, she will go to Maui for a marine and travel medicine workshop, where she’ll earn her certification as a diver. (Acquiring technical outdoor skills — in addition to teaching, curriculum development, and research — are part of the wilderness fellowship mission at Harvard.)

Throughout the year, there will be time out for technical climbs — a first for Cushing — in Grand Teton National Park and on Mount Rainier, a 14,411-foot peak southeast of Seattle.

And for three months next year, from February through April, Cushing will be in Nepal’s Khumbu Valley in time for the spring climbing season at Mount Everest. Sponsored by the Himalayan Rescue Association, she’ll practice medicine and conduct research on high-altitude physiology at the Pheriche Clinic, a one-day hike from Everest Base Camp.

The clinic, nestled in a remote valley 14,400 feet above sea level, is a long way from where Cushing grew up in Manhattan.

“I never spent time in the outdoors as a kid, unless you consider Central Park the outdoors,” said Cushing, 32. (She confessed to not even learning how to ride a bike until she was 20.)

But her undergraduate years at Tufts University drew Cushing to hiking and nontechnical climbing in New Hampshire. During and after medical school, she was drawn to more extreme adventures, including mountain biking in Moab, Utah; treks in mountainous Patagonia; and a weeklong winter snowshoe hike in Yosemite National Park.

Outdoors adventure, she said, “opened my eyes to the idea that you could put everything [you need] into a bag, and just go out into the middle of nowhere.”

Today, there’s an increasing need for physicians adept in the outdoors, said Cushing, who will use her time in Nepal to learn more about technical climbing.

“There’s this whole world out there of people doing (outdoors) things and somebody needs to help them do it safely,” she said. “I get to do what I love, and make it safer and better for other people.”

Wilderness medicine fits nicely into what Cushing said drew her to emergency medicine in the first place: the wide variety of challenging care it requires. “It keeps you interested and engaged and excited all the time,” she said.

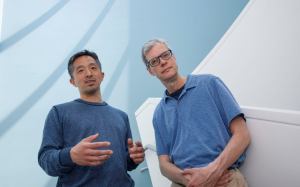

Harvard’s new Wilderness Medical Fellowship was the brainchild of N. Stuart Harris, an MGH emergency medicine physician, HMS assistant professor of surgery, and a longtime mountaineer, sea kayaker, and whitewater boater.

The fellowship has a dual mission, he said: to promote both wilderness medicine and environmental stewardship.

Cushing agreed. The medical community needs to be deeply engaged in ecological health, she said — an issue “not widely talked about yet.”

Cushing’s fellowship may last two years instead of one, since her critical time in Nepal comes late in the 2008-09 academic year. But there could be a second Wilderness Medical Fellow at Harvard next year anyway, said Harris.

Before studying medicine, he was an instructor at the National Outdoor Leadership School. Earlier this semester Harris presented a two-hour HMS workshop on high-altitude illness (his research specialty), along with emergency care protocols for lightning strikes and snakebites, two representative outdoor traumas.

For a month every spring, he leads U.S. and international medical students on a “Medicine in the Wild” course in southwest New Mexico’s Gila Wilderness. (In 2007, Cushing was chief resident on the teaching expedition.)

The course gets a literary twist from Harris, who before medical school earned an M.F.A. from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Mixed in with medical titles on the reading list are seminal works of the ecological imagination, including writing by Rachel Carson, Aldo Leopold, Edward Abbey, and poet Gary Snyder.

“There’s been a great and worrisome disconnect between organized medicine and advocacy for environmental issues,” said Harris. He’s working to establish a research collaboration between wilderness medicine specialists and HMS’s Center for Health and the Global Environment.

Excellent wilderness care is a natural companion to what physicians need to bring to (and from) the outdoors, said Harris – “greater awareness, and hopefully, greater advocacy.”