Julia Sweeney’s journey – from ‘God said Ha!’ to ‘God is silent’

Julia Sweeney, Grammy-nominated former star of “Saturday Night Live,” went looking for God – and found out there was no God. “And that’s the good news,” she said.

Sweeney described her Roman Catholic upbringing as “85 to 95 percent wonderful.” But she said embracing real life instead of an afterlife would be good news for the human race.

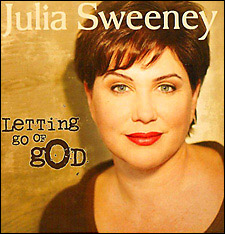

There’s more good news: Sweeney made her decade-long search for a spiritual path into a monologue play, “Letting Go of God.”

On Thursday (Oct. 26), it will be onstage at Harvard’s Sanders Theatre – a one-night New England premiere for the show, which played in Los Angeles throughout 2005.

“Letting Go of God” was described by the Los Angeles Times as “brave and hilarious.” It’s a tour of Sweeney’s humorous grappling with the Big Questions: the meaning of life, the fact of death, and the sweet unreality of heaven.

Earlier this month, Sweeney played nine shows of “Letting Go of God” at the Ars Nova Theater in Manhattan.

At Sanders, her performance is sponsored by the Humanist Chaplaincy at Harvard, and by the Harvard Secular Society.

Humanist Chaplain Greg Epstein said comedy is an excellent – not an odd – medium for delivering the humanist message. “When we laugh, we’re open,” he said. “We can just be brave and think and feel.”

Sweeney agreed. “It’s the sugar that goes with the bitter,” she said of comedy.

Sweeney had her first moment of spiritual bravery at age 10. Sitting in a pew at church, she suddenly thought, “This is a bunch of crap.” She told the parish priest about her doubts, expecting an argument. Instead, the priest burst into tears. It was enough to send a guilty Sweeney back to church.

Without his dramatic reaction, her life would have changed, Sweeney said in a recent interview from her Los Angeles home. “I would have been a scientist” and not a comedian, she said.

In her teens, Sweeney briefly flirted with the idea of becoming a nun. In adulthood, her faith tapered off into a fondness for Catholic culture, and only reappeared in bursts. “I dipped into my beliefs during crisis,” said Sweeney.

In 1994 came the biggest crisis of all: a cancer scare, and her brother’s lingering fatal illness. Grief and shock led Sweeney to a deliberate search for God.

Her first creative answer was “God Said Ha!,” a monologue play that was produced theatrically, then released as a CD, and was finally filmed for DVD release in 1997.

In the play, Sweeney is alone onstage with a couch and a candle. She wonders funnily aloud about illness, grief, family, lovers, and growing up Catholic. (One riff begins with her good-girl idea of a reward: “I was going to smoke myself a cigarette,” she said, “and buy the new book by the Pope.”)

The audio version of “God Said Ha!” got a Grammy nomination for best comedy album. The screen version was named Best Film at the Seattle Film Festival.

“I still believed in God then,” said Sweeney of writing the earlier play. But she continued the search for spiritual answers, reading deeply, arguing with Jesuits, and becoming estranged from her staunchly Catholic parents.

“I looked for God and it took me on this huge journey, and it led me to no God,” said Sweeney. “I felt like I was born again.”

Her final insight came suddenly, while she was doing what even stars do: scrubbing out the tub at home. She was 38.

“I wished people didn’t have to wait that long,” said Sweeney.

So she wrote “Letting Go of God,” out just this month as a CD. (It will be filmed in February.)

Spiritual journeys are often impossible, or muffled by the demands of modernity, she said.

“People in general are too busy to stop and get philosophy degrees, and then wonder about the meaning of life,” said Sweeney. “And then come up with their own ideas of how to behave in the world.” So religion – with its ready-made rituals, rules, communities, and expectations of civility – remains an attractive alternative to personal searching.

But humanism offers the same kind of structure as religion, said Sweeney: a way of behaving based on reason and compassion; a reason to feel responsible for each other; and “why not to tell a lie, even if there is no God to reprimand you for it.”

But as the idea of “Letting Go of God” took shape, Sweeney hit some rough air with her creative friends.

She described a meeting in New York with the producers of “God Said Ha!” They nixed the idea of a monologue about looking for God and finding he wasn’t there – in front of audiences that, presumably, still embrace the idea of God.

“What do you want?” a friend of Sweeney’s asked. “To make the audience feel like they’re stupid?”

“I don’t think anybody’s stupid,” said Sweeney. “I’m trying to say it was reasonable for me to believe in God. Then I looked into it, and now it’s reasonable not to.”

Bowing to pressure, Sweeney instead wrote and staged “In the Family Way,” a comedic monologue about being a single parent out in the dating world. It was a great show, she said, “but the whole time I was doing it I thought: This is not my great show. My great show is going to be the religious show.”

Her mother’s worries over a play about religion were more practical, said Sweeney. “She worried I’d never work in Hollywood again – that I’ll be back home without insurance.”

In “Letting Go of God” she uses her mother’s larger fears, doubts, and questions as a narrative device.

“If there is no God, how should we live? That’s what humanism provides,” said Sweeney.

Looking for God meant flying through turbulence philosophically, as well, said Sweeney. Like coming to grips with the fact that there is no afterlife.

But she came to think of her daughter Mulan, now age 6, as her afterlife.

“Having a child makes you have to worry about the future, and care about the future,” said Sweeney of her child. “And I want to influence her. That’s how I live on.”

By late 2004, “Letting Go of God” was ready for the 99-seat Hudson Backstage Theatre in Los Angeles, where it played through 2005.

The Harvard performance was arranged by the humanist chaplain Epstein, who met Sweeney in May at an American Humanist Association conference in Florida, where she performed part of “Letting Go of God.”

“When it was done, my first reaction was: I’ll have to quit my job” said Epstein. “She said everything I’d want to say in that show.”

Sweeney’s performance also reminded him that there are secular parallels to the healing community of religious worship.

“For humanists,” said Epstein, “one way we have to get that powerful experience is through the arts.”