Chertoff charts tactics and initiatives in war on terror

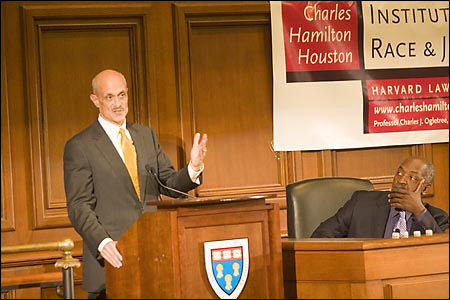

Toward the end of his speech Monday (Oct. 16) at Harvard Law School’s Austin Hall, Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff joked that speaking to university audiences might not seem the most favorable route to gaining public support for the Bush administration’s policies in the war on terror. “Of course there’s a lot of skepticism,” he said, “as there should be.” But open expressions of skepticism were muted, and for the most part the secretary was welcomed politely and even warmly by the audience of more than 100.

Chertoff began by presenting the legal case that the United States is indeed fighting a war on terror, as opposed to simply dealing with a more conventional criminal element in al-Qaeda and its adherents. “What differentiates war from crime?” he asked, mentioning Timothy McVeigh’s bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City as a case in point that “not every act of terror is necessarily an act of war.” Three things, he added, “put al-Qaeda in the category of war.”

First, we are dealing with an enemy that has clear political aims, as defined by Osama bin Laden as far back as 1997, in an interview Chertoff quoted with CNN in which the al-Qaeda leader declared jihad against the “unjust and tyrannical” U.S. government. Second, al-Qaeda and its ilk unquestionably harbor territorial ambitions; again, Chertoff quoted bin Laden, pointing out that the leader has frequently mentioned specific areas of the globe he believes should be brought under strict Islamic law as he interprets it, including all the lands dominated by ancient Persia, from North Africa to South Asia and as far west as Spain.

Finally, Chertoff noted that the scope of the damage today’s terrorists are capable of causing is “more similar to what one would expect of a state enemy than a mere criminal act.” The attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, he noted, caused the most harm inflicted on U.S. soil by an outside entity in the history of the nation. “It far exceeds what criminals ever dream of causing.”

He went on to point out that, although discussions regarding the war on terror tend to be academic and theoretical, the realities are often far more personal. “I certainly lost friends in September 11,” he said. “I’ve had people who lost someone on 9/11 look at me and say, ‘Please don’t let this happen again.’” He noted several times throughout his speech that this knowledge that a wrong move – or no move – could result in perhaps thousands of deaths is what motivates much of the work of the Department of Homeland Security.

That work, he added, is fraught with challenges, including the fact that information regarding the activities of terrorists is almost always fragmentary, contradictory, and incomplete. “But terrorism in real life doesn’t wait until you’re ready to evaluate the evidence,” he said. “The clock is against you.” Once arrests are made, he pointed out, the very existence of a thwarted plot is often challenged. “People seem to expect that one ought to wait until the fuse of the bomb is lit,” he said. “But the fact is you can never be sure that if you wait until the last minute that you haven’t waited too long. When the consequences of death are potentially in the hundreds of thousands, you become less risk-averse…. To know in your heart you had the ability to stop [an attack] is the fear that drives everybody who works with terrorism.”

Given that both the advantage and disadvantage of terrorists is that they operate in a network, Chertoff noted that the legal issues currently being debated to deal with the threat all involve communication, finances, and transportation – the three vulnerabilities of terrorist cells. He noted, too, that the new laws being made and the tactics being used to deal with this new threat – collecting fingerprints from known safe-houses on the battlefield to then run against the fingerprints of those entering the United States – should not unduly affect the lives of everyday citizens. He explained, for example, that there is no widespread wiretapping of Americans when a questioner compared the purported practice to those of George Orwell’s Big Brother. Chertoff pointed out that the limited wiretapping the federal government engages in has led to no false arrests so far and that it is used only on calls where one party is outside the United States and is believed to have a connection with known terrorists.

During the question-and-answer period, the secretary also addressed topics including the war in Iraq, stating that despite controversy over U.S. involvement, we must finish the job or risk allowing al-Qaeda to rise again; the difficulties of tracking nuclear smuggling; and biomedical research. He concluded after a questioner raised the topic of regaining the “hearts and minds” of the followers of bin Laden and other extremists. “I believe it is very important to make sure we continue to recognize that the vast majority do not adhere to bin Laden’s ideology,” he said. “World over, the rule of law and a sense of freedom is the best antidote. We must do what we can to work with the forces of law, freedom, and democracy, because every time people go to vote that’s a blow against bin Laden. That’s exactly what he hates.”