Delicate watercolors unveiled again

First showing of these treasures since 1936

The labels hadn’t yet been hung on the pictures when Theodore Stebbins Jr. unlocked the gallery gate to give a preview of the Fogg Museum’s new show, “American Watercolors and Pastels, 1875-1950.”

But that hardly mattered.

Stebbins, curator of American art at the Fogg, knows these pictures like old friends.

Which isn’t to say that he and his assistant curator, Virginia Anderson, aren’t continuing to make new discoveries about them, even as the last details are tended to before the show opens this weekend.

The exhibition comprises 52 watercolors and pastels, drawn primarily from the Fogg’s own holdings, that collectively describe the arc of a golden age of watercolor. It was between 1875 and 1950 that watercolor became a medium not only for preparatory studies but finished works to be displayed and sold. And with only a couple of exceptions, this show consists of paintings fashioned as ends in themselves, “even down to the sketchiest Whistler,” as Stebbins puts it.

The exhibition shows off the Fogg’s strength in the works of four giants of the founding generation of American watercolor art – Homer, Sargent, Whistler, and LaFarge – as well as their successors. But the rounding out of the show with the inclusion of nine works on loan, from later artists not so well represented in Harvard’s holdings, is meant as a discreet signal that “we’re still collecting,” as Stebbins puts it.

‘American Watercolors and Pastels, 1875-1950’ opens April 8 at the Fogg Museum, 32 Quincy St., Cambridge, and runs through June 25. Visit http://www.artmuseums.harvard.edu for details.

Because of their sensitivity to light, watercolors and other works on paper can be displayed only for brief periods of time. The last occasion for a major exhibition of watercolors like this at the Fogg was in 1936.

The present show grew out of a cataloging project now under way at the Fogg, which reminded the museum’s curators just how extensive their holdings are.

In the room showing off nine of the Fogg’s Homers, Stebbins formulates his assessment of the artist: “Many think Winslow Homer is the greatest American watercolorist. Probably I don’t disagree.”

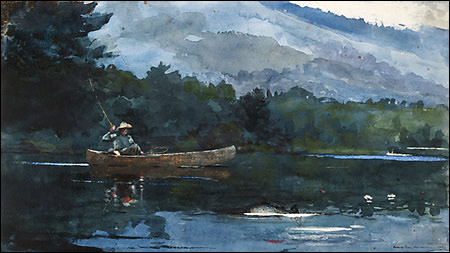

Of “Adirondack Lake,” a work dating from 1892 showing a fisherman in a canoe about to pull in a big one, he says, “In modern art terms, this is all about blues – the darkness that occurs at the very end of the day.”

There isn’t any sunlight left, and the bugs are beginning to bite, and so are the fish. We see the fish, the pole bent under its weight; we see the taut fishing line, and the net in the fisherman’s left hand. In a moment, it will be over for the fish, but Homer catches the instant, heightened with flashes of white where he has cut out bits of color with a razor to set off the fish and the boat.

In “Hunter in the Adirondacks,” also from 1892, Homer captures another moment in what he and the Hudson River School thought of as the “American Eden.” Stebbins points out how the artist has managed to convey a breeze through a series of little scrapes on the paper – and a single yellow leaf caught on the wind. “I’ve never noticed that leaf before.”

Another discovery comes during a look at Homer’s “Mink Pond,” a magical close-up of flower, fish, and frog. Anderson notices that the artist signed the painting twice: Underneath the obvious red signature is a less-visible signature in black.

As one of the happy accidents of the hanging of the show, visitors will enter the exhibit through a room representing three artists in the middle of the period covered: Edward Hopper, John Marin, and Charles Demuth. The three Hoppers in the show, particularly, hanging on the wall facing the entrance “have great physical presence,” and will, Stebbins predicts, draw visitors in.

These paintings, such as “Highland Light,” show the artist as very much an architectural modernist, unembarrassed to have such less-than-picturesque elements as power lines in his pictures. They also show him painting in the summer, outdoors, working quickly, on pictures that required no human models.

The Hoppers are flanked by two sets of “twins” – two paintings of Mt. Chocorua in New Hampshire by John Marin, done under different conditions to suggest a compare-and-contrast exercise; and two fruit-and-flowers still lifes by Charles Demuth, which similarly invite comparison.

Marin’s contribution, as the pictures on view demonstrate, was to translate what was going on in the European art world at the time and translate it into an American idiom. “Marin goes to France,” Stebbins says, and on his return, “makes Cubism work with the American landscape.”

One of the Demuths, “Fruit and Sunflowers,” is a tour de force, demonstrating a very precise style in the unforgiving medium that is watercolor: It affords no opportunity to paint over mistakes, as oils do. Yet with judicious use of blotting and other techniques, Demuth suggests precisely the three dimensions of a green pepper and other elements of the composition.

Among the pastel offerings in the show is a self-portrait by William Merritt Chase – “probably the most famous pastel in American art,” Stebbins offers. It’s a portrait of the artist as an artist – holding a palette. Stebbins and Anderson suddenly notice this for the first time, but there it is, the artist’s thumb through the hole.

Then a question arises: What kind of palette? Is Chase depicting himself as an artist who works in mere chalk – or the exalted medium of oils?

“Hmm. We’ll have to look into that,” Stebbins says.

Even with old friends, there’s always more to get to know.

Share this article