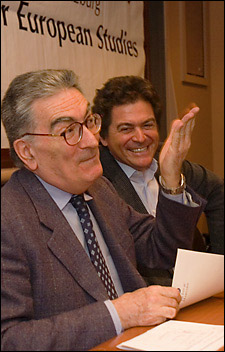

Alesina discusses ‘sick man of Europe’

Italy is in fiscal and political trouble, say scholars

In Denmark, it takes two days to open a new business; in Italy, two months.

Alberto Alesina, the Nathaniel Ropes Professor of Political Economy, mentioned this fact to emphasize the economic reforms that Italy’s new prime minister, Romano Prodi, must bring about if he hopes to change Italy’s current status as “the sick man of Europe.”

Alesina spoke as part of a presentation at the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies: “Whither Italy Now?: A Panel on the Italian Elections.” The panel also included Gianfranco Pasquino of the University of Bologna and Serenella Sferza of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Italy Program. Charles Maier, the Leverett Saltonstall Professor of History, was moderator.

“Italy has very serious economic problems,” Alesina said. “It needs an injection of free-market, liberal, economic reforms.”

Among the reforms he recommended were reducing the high income tax rate, cutting back on bloated public employment and the overly generous pension system, enhancing the service sector, and making it easier to fire workers.

“These things have to be done quickly and all together,” he said.

But will the Prodi government be able to accomplish such sweeping reforms? None of the panel members was terribly hopeful about such a result.

One reason for their pessimism is Prodi’s slim margin of victory. Prodi’s center-left coalition, the “Union,” received 49.8 percent of the vote, compared with 49.7 percent for the center-right coalition, “House of Freedom,” headed by self-made billionaire Silvio Berlusconi.

Among Berlusconi’s many business holdings is the media company Mediaset, which controls Italy’s three main television channels. Commentators suggest that his media dominance is one of the reasons for his success in Italy’s volatile political climate. He is the first prime minister since the end of World War II to finish out a full five-year term.

Unlike his opponent Prodi, a low-key former professor who served as prime minister previously and also as president of the European Commission, Berlusconi is known for his flamboyant personality and frequently outrageous pronouncements. In the run-up to the election he compared himself to both Napoleon and Jesus Christ, insulted influential business leaders, and used an impolite epithet to characterize anyone stupid enough to vote for the other guy.

So close was the election that it might easily have gone the other way. According to Pasquino, Berlusconi’s recent attempt to secure a victory by changing the electoral law actually had the opposite effect.

“Had Berlusconi not changed the electoral law, he would have won. Next time Berlusconi ought to have better consultants,” Pasquino said.

But despite Berlusconi’s miscalculation, Pasquino believes he will continue to be a factor in Italian politics.

“Berlusconi will stay. He has nothing else to do, he enjoys it, and he wants to make life difficult for the center-left government. I believe he will fight all the way.”

Sferza agreed that the new government will not have an easy time of it. She said that the essence of Prodi’s less-than-decisive victory was best captured by a drawing on the cover of Italy’s weekly magazine L’Espresso, which showed a tiny Prodi perched on a oversized Louis XIV chair.

“His performance was very disappointing. The small majority is sure to create a leadership problem,” she said.

Another of Italy’s problems is that both its economy and its political system are oriented toward the elderly, Sferza said.

“Italy is becoming a gerontocracy where new, emerging political leaders are in their late 50s. [Berlusconi is 69 and Prodi is 66.] It’s a country where lots of money is spent on pensions, and the economy is skewed toward older citizens.”

Sferza believes that the difficulties she has encountered placing MIT students as interns in Italian companies illustrates the country’s prejudice against youth.

“No one in Italian companies believes that students have anything to contribute. They only use them for menial work and they don’t think they should be paid,” she said.

And yet, while the prospects for needed reforms do not look good, all of the panelists held out some hope that the new government might be able to muster enough cooperation to bring about positive change.

“It’s true that Prodi is not a bold or innovative leader,” said Alesina, “but this is probably his last political job, so why not try?”