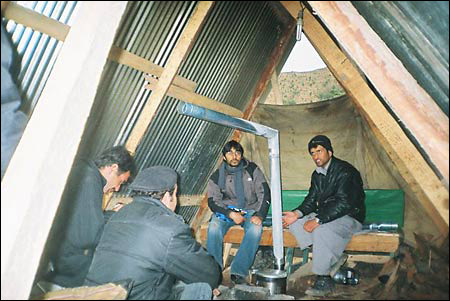

Winter in a Pakistani medical tent

Three HSPH students and an HMS fellow greeted the new year by dispensing medicine and care in the mountains of Pakistan

In late December and January, while most of us found ways to remain warm and snug in the face of a mild winter, three students from the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) and a research fellow from Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) braved an unusually cold winter in the mountains of Pakistan. They had traveled there under the aegis of the Real Medicine Foundation to provide medical care and other assistance to survivors of that country’s Oct. 8 earthquake.

The earthquake killed about 87,000 people, injured thousands, and leveled villages. “It was hard for me to understand until I went there,” said Giorgio Pietramaggiori, a research fellow in surgery at BWH, “that entire cities were down and there was nothing left. There were all these people living in shelters and tents and they didn’t have any heat or hot water. They were essentially abandoned.”

Omar Amir, a master’s degree student at HSPH, said that the easily accessible areas, lower on the mountains, were well taken care of by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). But the Shawal Moizullah union council – an area near the epicenter of the quake comprising villages and hamlets above 5,000 feet, and populated by approximately 20,000 people – had been all-but-ignored.

“It’s been neglected because it’s practically inaccessible,” said Amir. “There are practically no roads, and what roads there are often get blocked by landslides.”

The team arrived in Islamabad on New Year’s Eve. The next day they headed for the highlands. “It had rained all night and we were advised not to go because the roads were in very bad condition,” said Fabian Toegel, a physician and an M.P.H. student at HSPH. “But we thought it was important.” The journey did prove precarious on the slippery muddy roads to the mountain village of Jabri, where the NGO known as HOAP (Helping the Oppressed and Powerless) had set up a medical tent.

“The people in the camps in Islamabad were a lot better off than the people up in the mountains,” said Helen Ouyang, a fourth-year medical student and an M.P.H. student at HSPH. “The people in Jabri were in pretty good spirits, all things considered, but you could tell that they were pretty run down.” Most of the villagers lived in unheated tents, donated by HOAP or other NGOs.

“These are people who are used to having a little firewood stove in their houses to provide heat,” said Amir. “Now, they sleep in tents and they can’t light fires inside the tents because of the risk of fire and lack of ventilation.” Nighttime temperatures frequently drop below freezing.

The medical tent

Pietramaggiori knew that the days would start early, with a 5:30 call to prayers. His first stop was the medical tent. Soon the patients began to arrive. Pietramaggiori, Toegel, Ouyang, and three Pakistani doctors would care for a ceaseless flow, perhaps 60 a day, until the late afternoon. They treated injuries caused by the earthquake itself and a host of post-quake illnesses.

Amir, the group’s record keeper, noted that 62 percent of the children they saw in the clinic had acute respiratory infections. The adults, in addition to reporting respiratory infections, suffered from skin infections and urinary tract infections.

The Real Medicine Foundation had sent the team with approximately $500 of medicines, primarily antibiotics. These were dispensed within a week.

Pietramaggiori, who is a surgeon, was particularly struck by the incidence of infected wounds. Many injured by the earthquake in October had received their initial treatment at hospitals further down the mountains. But it was too onerous a trip to go back and forth for wound care and cleaning.

The injured, figured Pietramaggiori, could care for their own wounds if they only had a few inexpensive supplies and the knowledge of how to use them. He created a wound care kit, containing antibacterial gel soap (which does not require water), sterile saline solution, bandages, gauze, tape, and disposable gloves. The kit costs about $1.

Pietramaggiori and Amir, with support from the Ministry of Health of Pakistan, held a series of workshops with local health care providers and with patients and their families on the production and use of the wound care kits. “The idea was to create something that anybody could use, so that it would be easy to train the patients and the local health care dispensers,” said Pietramaggiori. “We provided simple pictorial instructions, with instructions also in English and Urdu: wash your hands, wear the gloves, etc. And all the materials needed are very cheap and any health care provider should have access to them.”

Dispensing medical care in the void

The team was surprised to find that most of the people they treated had had no access to health care before the earthquake. “There was a clinic, called a basic health unit, in Jabri,” said Amir. “It was supposed to be staffed by a doctor, a lady health worker, and a medical technician. The idea was to offer basic primary health care services.” However, there had been no doctor or health worker at the clinic for several years, and the technician was selling the government-supplied medications for a profit.

To fill this void, the students, backed by the Real Medicine Foundation, hired a local doctor for a term of six months. “Being there for two weeks gives you the opportunity to help a large number of victims, but you have to provide continuity of care in order to be really effective” said Pietramaggiori. With the new doctor in place, the care can continue.

The team came up with additional plans, including the hiring of women health workers (females in this area are reluctant to seek medical care from men), building a permanent clinic, and obtaining a jeep. In addition, they would like to produce an imitation of a tent-heater design that originates in northern Pakistan. This heater has no open flame and has an exhaust system to vent the smoke outside of the tents.

Team members expressed a desire to return to the area to continue to help the people. And they were pleased with what they’d been able to accomplish. “It was very rewarding,” said Amir, “to see that even as a small group of individuals, we could do something to benefit these people.”