Ozick assails writers’ lack of responsibility

Holocaust writers should ‘restrict imagination’

The writer of fiction may alter and distort reality in any way he or she pleases, as long as the result possesses a consistency that allows readers to suspend their disbelief and accept the imaginative world the writer has created.

The exception to this rule is when a fiction writer takes on the Holocaust.

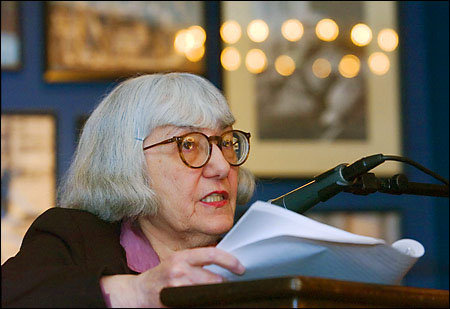

This was the argument presented by writer Cynthia Ozick in her Nov. 28 talk “The Rights of Imagination and the Rights of History.” The lecture, which honored the memory of novelist Saul Bellow, was co-sponsored by the Center for Jewish Studies, the Department of English and American Literature and Language, and the Alan and Elisabeth Doft Lecture and Publication Fund.

Ozick, a highly respected writer of short stories, novels, and essays, is the author of “The Shawl,” “The Pagan Rabbi and Other Stories,” “The Puttermesser Papers,” and, most recently, “Heir to the Glimmering World,” the story of a Jewish immigrant family in New York who are supported and exploited by a character based on Christopher Milne, who was himself the model for his father A.A. Milne’s “Christopher Robin” books.

It may be that in Ozick’s view other historical events beside the Holocaust require restrictions on the fiction writer’s imagination, but these other events did not come up. Ozick’s only examples of works that cross the line into imaginative irresponsibility were Holocaust novels: “Sophie’s Choice” by William Styron and “The Reader” by German writer Bernhard Schlink.

Ozick found fault with Styron for making the heroine of his novel a Polish Catholic rather than a Jew. It is true, she said, that 75,000 Polish Catholics were murdered at Auschwitz, and the suffering and death of those Poles was no less horrible than that of the death camp’s Jewish victims. The difference is that Hitler did not deliberately set out to totally eradicate Poles along with their religion and culture from the face of the Earth as he did with the Jews. It therefore behooves Styron to place a typical (i.e., Jewish) victim of the Holocaust at the center of his tale. To do otherwise is to “dilute, obscure, and ultimately to expunge the real nature of the Holocaust.”

Likewise with Schlink’s book, “The Reader,” a 1999 Oprah’s Book Club selection. In this story, a young man has an affair with an older woman who turns out to have been a Nazi death camp guard. The plot turns on the fact that she is illiterate, and her inability to read is the reason she was unwittingly shunted into a job in the concentration camp.

Absolving the character of responsibility based on her illiteracy is unacceptable, according to Ozick. Such an occurrence may have been possible, but it is unlikely given that Germany at that time had the highest literacy rate of any country in Europe. By placing such an atypical case at the center of his narrative, Schlink deflects the reader’s attention away from the real nature of the novel’s historical context, and given the importance of that history, Ozick finds such a maneuver indefensible.

“We should beware of giving too much credence to the seduction of narrative when narrative dares to enter history,” she said.

Ozick, 77, a small woman in owlish glasses and iron-gray bangs, warned her audience at the outset that her talk “may provoke discord and dissent,” and the prediction proved accurate. The audience’s questions revealed a prevailing skepticism, but none of these objections caused Ozick to budge from her original position.

One woman asked how far Ozick would take her argument. Would she, for example, object to novels about serial killers on the grounds that they might encourage violence against women?

“I would stick up for novels about serial killers,” Ozick replied. “The reason is that the government is not institutionalizing serial killers. The instances are trivial. The whole society is not geared to produce them.”

Another audience member questioned Ozick’s assertion that the Nazis did not set out to destroy the Poles with the same relentless thoroughness as they did the Jews. Recent research, he said, shows that toward the end of the war the Nazis were beginning to systematically kill Polish clergy and intellectuals. Ozick said she doubted whether this behavior amounted to the same thing as Hitler’s Final Solution.

Someone else commented that Ozick’s argument reminded him of Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe’s essay on Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” in which he condemns Conrad for suggesting that the worst thing about African colonization is that it produces moral depravity on the part of the European colonizers. No, says Achebe, the worst thing is the suffering it caused to Africans.

But Ozick would have no part of this comparison. The target of Conrad’s criticism was savagery, whether it was perpetrated by Africans or Europeans, she said.

If “Sophie’s Choice” was the only Holocaust novel, another audience member objected, there might be grounds for condemning Styron’s choice of a Polish Catholic woman as its main character. But given that there are many other narratives covering the same ground, “it seems to me to be a perfectly valid exercise of the novelistic imagination.”

Again Ozick flatly disagreed.

“The Holocaust is a story that should be told,” she said, “and Styron didn’t tell it.”