Ivory-billed woodpecker: Ornithology’s holy grail

Birdman Gallagher recounts the day of discovery

Tim Gallagher and Bobby Harrison almost flopped into the mud of Arkansas’ Bayou de View in their haste to get out of the canoe. They crashed through the undergrowth after the flashing black and white bird that was threatening to vanish among the huge cypresses.

After dashing across the soggy ground, through brambles, and over fallen logs, the bird finally disappeared. Gallagher stood stunned. Harrison fell down on a log, overcome by emotion.

“I saw an ivory-bill!” he said.

After a half-century of apparent extinction, in February 2004 the ivory-billed woodpecker came back to life.

Gallagher, editor of Living Bird magazine and director of publications for Cornell University’s Laboratory of Ornithology, told the tale of finding ornithology’s holy grail Thursday night (Oct. 6) to a packed house in the Geological Lecture Hall.

“It was just insane, the biggest adrenalin rush we’d ever had,” Gallagher said of the find. “This is really the most amazing thing that ever happened to me.”

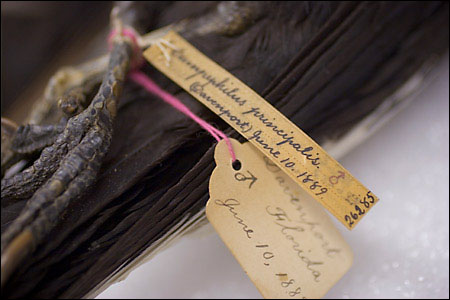

The talk, “Rediscovering the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker,” was sponsored by the Harvard Museum of Natural History (HMNH). The museum plans to mount its own ivory-billed exhibit, displaying both birds and a rare ivory-billed woodpecker nest from its collection.

“The story of the rediscovery of the woodpecker and the controversy surrounding it is certainly one of the most exciting and dramatic conservation/nature stories of the year,” said HMNH Executive Director Elizabeth Werby, who introduced Gallagher.

Despite occasional unconfirmed sightings, scientists had thought the ivory-billed woodpecker was extinct in the United States after 1944, and in Cuba after 1948. Never common, with a huge home range, America’s largest woodpecker died out in the decades after the Civil War as loggers clear-cut the forests that they lived in. The bird also became a target of private collectors, which accelerated its decline.

The last stand in which the birds were reliably found, the Singer Tract in northeastern Louisiana, was logged in the late 1930s. The last accepted U.S. sighting was of a female in 1944.

Scientific forays after that into the bird’s swampy Deep South habitat came up empty, but tantalizing evidence continued to trickle in. Tales of sightings from hunters and others penetrating the bayous remained unconfirmed, but slowly transformed the bird into an ornithological Big Foot.

Scientists remained skeptical because of the pileated woodpecker, a bit smaller than the ivory-billed, but similar in color and habitat. The two birds are easily confused.

The February 2004 sighting by Gallagher and Harrison – both experienced birders – wasn’t enough to win over the skeptics. But it did mobilize a small army that over the next year recorded several more sightings, collected audio recordings, and ultimately videotaped one in flight. Their findings were published in June 2005 in the journal Science.

Gallagher’s tale blended humor, history, and sheer doggedness. Researching a now-published book on the ivory-billed sightings in recent decades, “The Grail Bird,” Gallagher had traveled around the South, conducting interviews with people who claimed to have seen it.

But it was Gene Sparling who changed everything. Kayaking alone in Cache River National Wildlife Refuge in early February 2004, Sparling saw a bird that appeared to be an ivory-billed woodpecker. Sparling posted his sighting on the Internet and news soon reached Harrison and Gallagher. Two weeks later, the pair revisited the area with Sparling.

A wildlife photographer since he was a teenager, Gallagher said he didn’t realize how fleeting his view of the bird would be. If he ever laid eyes on an ivory-billed, Gallagher figured he’d come back with photos. In describing the bird, he said its black and white plumage is very dramatic: deep black and startlingly white. The bird that he and Harrison spotted was most likely a female, since it lacked a male’s red crest. America’s largest woodpecker, its size also makes an impression. Its body is 18 to 20 inches long and it has a 30- to 31-inch wingspan.

Though it is possible that they stumbled upon the last remaining individual ivory-billed woodpecker, Gallagher said he believes that the birds remain widespread in very low numbers. As forests re-grow, the birds remain shielded from all but the most intrepid humans by their inaccessible home.

For the immediate future, Gallagher said he plans to head back to Bayou de View this fall, when higher water levels and the lack of foliage make both travel and viewing easier. He’s hoping to not only spot more birds, but to find a nest. He also plans to pursue other sightings he’d heard of before the life-changing canoe trip with Harrison and Sparling.

“Occasionally a hunter will come up with a really good sighting, and they’re all in the places you’d expect [to find ivory-billed woodpeckers],” Gallagher said. “They’re so few in number they can be off the radar screen.”