Panel talks about tradition of protest literature

Text and images that say ‘you are not alone’

From Tom Paine’s “Common Sense” to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” to the rap anthems of Tupac Shakur, protest literature has moved the masses, but generally left the critics cold.

“There are hardly any books or critical discussions about protest literature,” said Zoe Trodd, a Ph.D. candidate in History of American Civilization.

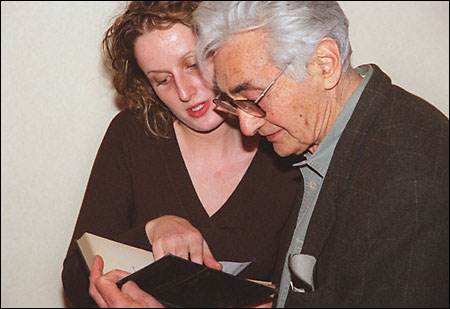

Trodd, a graduate of Cambridge University who came to Harvard on a Kennedy Memorial Fellowship and “just fell in love with American literature,” hopes to change that. Her book “American Protest Literature” will be published next year by Harvard University Press. She is already co-author with John Stauffer, professor of English and American Literature and Language, of a book on abolitionist John Brown – “Meteor of War: The John Brown Story” (2004), and serves as head teaching assistant in Stauffer’s Core course on protest literature.

On April 1, Trodd moderated a panel discussion on protest literature at the annual meeting of the New England Modern Language Association, held in Cambridge, Mass. The panel included Stauffer; Tim McCarthy, former history and literature lecturer at Harvard; Paul Lauter, Trinity College English professor; and Howard Zinn, professor emeritus of political science at Boston University and the author of the popular “A People’s History of the United States.”

Stauffer stretched the term protest literature to include photography. He showed photographs of emaciated Union soldiers held in Confederate prison camps during the Civil War and described how the proliferation of those images in the news media helped convict the commandant of Andersonville prison camp, Henry Wirz, of crimes against humanity. Similarly, Eddie Adams’ photo of a South Vietnamese general executing a suspected Viet Cong shocked many Americans and led to the largest shift in public opinion during the Vietnam War. Stauffer’s final exhibit was one of the photos from the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse scandal. These have had a lesser effect on public opinion, he said, because they emphasized humiliation rather than physical violence and because their aesthetic quality was not high.

McCarthy discussed the difficulty of defining protest literature and suggested as a broad definition, “works of art that need to be interpreted for their intent.”

He spoke about the 40-year campaign of the abolitionists and their creation of a broad print culture to argue against slavery.

“This is not happening today to the same extent. These were relentless people,” he said.

Lauter read the poem “Indian Names” by a now nearly forgotten poet, Lydia Sigourney. The poem was published in 1834 to protest the Indian removal policy of President Andrew Jackson.

“Do works survive the conflicts in which they engage?” Lauter asked. His answer was that such works “never fully transcend the moment of creation, nor are they intended to.” However, “the revival of political concerns enables us to read these texts anew by reorienting our consciousness.”

Zinn described protest literature as “any form of communication that engages social consciousness and may move someone to action.”

Such works may shock us into action by informing us of problems we were unaware of, like the work of Upton Sinclair or Rachel Carson. Other works may cause us to doubt our assumptions through the use of satire and absurdity, like Joseph Heller’s “Catch-22.”

Finally, Zinn said, “all protest literature says to the reader, ‘have hope – you are not alone.’”