‘Birth of a Nation’ – the remix

DJ Spooky presents new view of contentious classic

The show began with a blast of throbbing, high-decibel techno music from which the melody of “The Star-Spangled Banner” fleetingly emerged like a familiar voice shouting for help in the midst of a hysterical crowd.

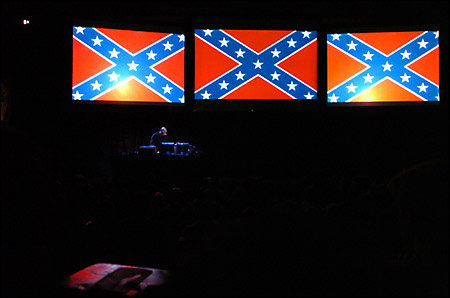

Simultaneously, on three large screens, the flags of all nations flashed in succession, a near blur of primary colors, stars, crescents, eagles, and swords. After several minutes, the screens suddenly froze into one fixed image – the defiant crossed bars of the Confederate flag.

Perhaps the symbolic shock was enhanced by the fact that the presentation was taking place in Sanders Theatre, the cavernous apse of Memorial Hall, a building dedicated to Harvard’s Union dead. Whatever the reason, it was clear at that moment that Paul D. Miller had indeed come to rock the house.

Miller is a conceptual artist, composer, filmmaker, and writer who is more commonly known by his club name or “constructed identity” of DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid. Steeped in postmodern theory and fascinated by the impact of digital technology on popular culture, Miller has forged a career that spans the dance scene, the world of art galleries and museums, musical collaborations with the likes of Pierre Boulez, Wu-Tang Clan, and Yoko Ono, and writing in The Village Voice, Artforum, and other periodicals. A book of his essays and an accompanying CD, “Rhythm Science,” was published last year by MIT Press.

Miller was at Harvard on March 11 to present “Rebirth of a Nation,” his remix of D.W. Griffith’s cinematic epic “Birth of a Nation.” His appearance was sponsored by the Office for the Arts at Harvard and Harvard Friends of Amnesty International.

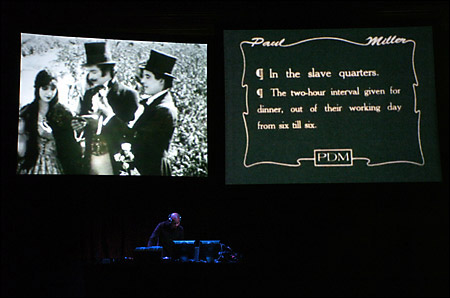

Griffith’s film has troubled and polarized audiences since it was first released in 1915. A work of great power, which introduced many of the cinematic techniques that were to become part of the standard vocabulary of moviemaking, the film also perpetuates a full gamut of negative black stereotypes, vilifies Northern liberals, and portrays the Ku Klux Klan as the heroic saviors of the post-Civil War South.

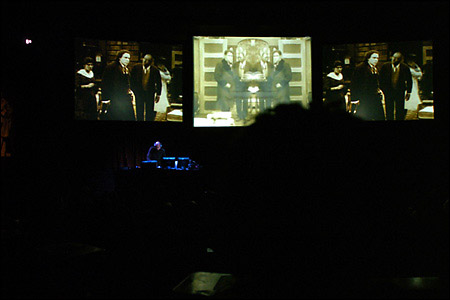

Miller’s work, which he describes as a “digital exorcism,” uses repetition, mirror imaging, black-white reversals, overlays, and other forms of distortion to invoke, as he says in a written statement, “a parallel world where Griffith’s film acts as a crucible for a vision of a different America. … ‘Rebirth of a Nation’ asks that the viewer break the loops holding the past and present together so that the future can leak through.”

The work unfolded to an original musical accompaniment influenced by minimalist composers such as Phillip Glass and Steve Reich but that also incorporated earlier elements such as 1930s blues man Robert Johnson’s “Phonograph Blues.” Standing at a table covered by laptops and other electronic paraphernalia, Miller coordinated images and music to create an improvised performance out of previously recorded material.

Images of dance numbers choreographed by Bill T. Jones, another artist whose work explores the history of blacks in America, appeared juxtaposed with scenes from Griffith’s film, highlighting the theme of stereotyped body language. The inclusion of work by Jones and Johnson emphasized the fact that black artists have been responding both critically and creatively to racial stereotyping by whites since Griffith’s film was released, and no doubt long before that.

In fact, as Miller pointed out during the discussion period, moderated by film critic Elvis Mitchell, a visiting faculty member in Visual and Environmental Studies, it was the outcry among blacks against the stereotypical images and historical distortions of Griffith’s film that in part stimulated the emergence of the black cinema.

Asked by Mitchell about the origin and purpose of his work, Miller replied: “I was thinking about how the cinema can be used to interrogate the media. I want audiences to leave with a sense that it doesn’t have to be this way.”

How successful is Miller’s “digital exorcism” in driving out the racist demons that are so unambiguously manifested in “Birth of a Nation” and that still continue to haunt and trouble American society in a more clandestine form? After the showing, one member of the audience was heard to say that he wished Miller had gone further by using one of the three screens to display accurate information on Reconstruction, allowing audience members to compare Griffith’s portrayal with a more objective version and draw conclusions for themselves.

Considering how frequently during the discussion period Miller affirmed his love of irony and ambiguity, it seems unlikely that such a nakedly pedagogical procedure would have suited him. But the suggestion does bring out a weakness in Miller’s work. For all the digital power at his disposal, for all his ability to sample and loop, cut and paste, and set the resulting visuals to a thunderous, electronically created musical score, the postmodern sensibility at the heart of his project seems in the end a poor match for the reactionary rage and rhetorical fury that drives Griffith’s film.

In spite of Miller’s digital manipulations, what remains of Griffith’s images still has power to move us, regardless of how morally and politically repugnant the premises on which they are based or the ideas they convey, perhaps because nearly a century of cinematic imagery, derived from Griffith’s pioneering efforts, have conditioned us to react in this way.

At the same time, the politics of “Birth of a Nation” are so out there, so clearly at odds with current attitudes on race as well as with historical fact, that the sophisticated and racially mixed audience at Sanders Theatre would probably have seen just as much irony and distortion had they viewed the original film instead of Miller’s remix. This raises the question, exactly what purpose does the remix serve? Is it all just a postmodern exercise in bricolage? And is that perhaps the point, that a potent and dangerous text can be dismantled and travestied by a self-liberated descendent of its intended victims?

It seems likely that until the conceptual clarity and executive skill of young artists like Miller catch up with the technological means that lie almost too close at hand, the ghosts inhabiting Griffith’s disturbing masterpiece and American society at large will continue to haunt.