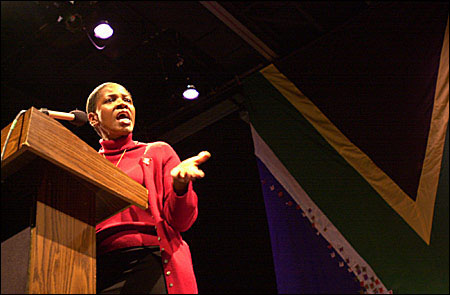

Ten years after apartheid

Mpho Tutu says South Africa still struggling with legacy of discrimination

“Were the government to spend on all children what the previous government spent on white children, the entire national budget would go for education,” said Mpho Tutu, who spoke at Harvard on Jan. 14 as part of the American Repertory Theatre’s South Africa Festival.

Tutu, the daughter of 1984 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Bishop Desmond Tutu, was ordained to the Anglican priesthood in January 2004 and is currently serving as a clergy resident at Christ Church in Alexandria, Va. Before entering the Master’s of Divinity program at Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge, Mass., in 1999, Tutu was director of the Discovery Program, a children’s ministry of All Saint’s Church in Worcester. In addition to her ministerial duties she continues to serve on the Board of Directors of the Reinvest South Africa (RISA) Charitable Trust.

In her talk, Tutu highlighted what she described as South Africa’s “grab bag” of triumphs and failures over the past decade.

“Effectively, there has been an extreme population growth because the previous government only concerned itself with one-third of the population,” she said.

She compared the present state of affairs to a couple living comfortably on their income who are suddenly faced with having their three children move back home along with their spouses, children, and in-laws. But while the economic consequences of rectifying South Africa’s former inequality help to explain some of the difficulties the country has experienced, Tutu did not absolve its leadership from accountability.

“Programs for ending poverty have been inadequate,” she said. “The government could do more, which is not to say they haven’t done anything.”

South Africa is still suffering from a crisis in homelessness, which makes America’s homelessness problem pale by comparison. On the outskirts of major cities, she said, one can see “miles upon miles upon miles of people living in shanties and tin shacks.”

Added to this is the terrible problem of HIV and AIDS, a problem that the government has recognized tardily and with great reluctance.

“It was unconscionable that the government had to be taken to court to force it to supply medicine to slow the spread of AIDS,” she said.

The AIDS crisis in Africa has been devastating, she said, comparable in its impact to the slave trade. The social costs of the disease are particularly staggering because it typically strikes young adults just as they have finished their education and are ready to begin contributing to society.

“At the point where society has finished investing in the individual, that is when people become infected with AIDS and are no longer valuable to society. As a result, we are losing a generation of doctors, lawyers, teachers, bank managers, and business people. There will no longer be a transfer of culture from parent to child. The absence of government action has been worse than merely shortsighted.”

Tutu expanded on her criticism of the government during the question-and-answer period, accusing government officials of doing “a lot of pocket self-lining,” despite the fact that they had “a mandate to be different from the government before. It wasn’t the blackness of your faces that we cared about; it was the difference in your attitudes.”

In response to a question about recent attempts by the government to quell dissent, Tutu said she thought such efforts by those in power represented a “fairly human impulse. But there are still enough people in the country who are passionate about preserving a genuine and vibrant democracy. South African democracy was really hard-won, and we cannot let this treasure slip.”

Tutu had warm praise for South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which her father headed. Apartheid, she said, created “atomized communities” of whites, blacks, and colored (people of mixed race), with little awareness of one another and little sense of belonging to the same society.

“The Truth and Reconciliation Commission gave us all a common story,” she said.

Giving both victims and perpetrators a forum to relate their histories will lay the groundwork for the eventual reconciliation of the country’s schisms.

“Healing doesn’t start to happen until the stories are told.”

Another “silver lining” to South Africa’s years of institutionalized racial inequality is the “do-it-yourself culture” that arose among the country’s poor, black population in response to government neglect. Orphanages, clinics, maternity hospitals, and other “home-grown agencies have grown up to fill the need,” Tutu said.

Looking back over the past decade, Tutu concluded that on balance, South Africa’s achievements have outweighed its failures.

“When you look at how far we’ve come, it seems unimaginable that it’s only been 10 years. On the whole, I think we’ve done really good.”