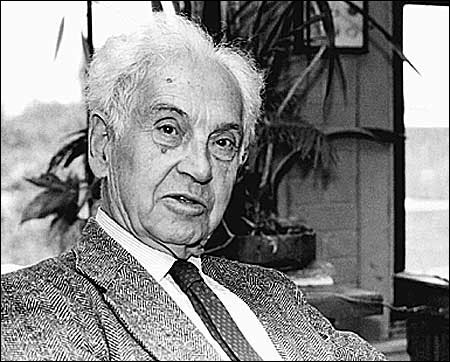

Ernst Mayr, giant among evolutionary biologists, dies at 100

Mayr had brilliant, nearly 80-year career

Ernst Mayr, the Harvard University evolutionary biologist who has been called “the Darwin of the 20th century,” died on Feb. 3 at a retirement community in Bedford, Mass. A member of the Harvard faculty for more than half a century, he was 100.

Mayr’s death came after a brief illness, his family said.

Widely considered the world’s most eminent evolutionary biologist and even one of the 100 greatest scientists of all time, Mayr joined Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences in 1953 as Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology and led Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology from 1961 to 1970. He retired in 1975, assuming the title Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology Emeritus.

“Professor Mayr’s contributions to Harvard University, and to the field of evolutionary biology, were extraordinary by any measure,” said William C. Kirby, Edith and Benjamin Geisinger Professor of History and dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard. “As a professor, museum director, benefactor to our library of comparative zoology, and leading mind of the 20th century, he shaped and articulated modern understanding of biodiversity and related fields. With sadness, we note his passing; with gratitude, we thank him for his legacy.”

Mayr’s work in the 1930s and 1940s, while a curator at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, quickly established him as a central figure in the neo-Darwinist evolutionary synthesis, the resurgence of evolutionary biology widely regarded as one of the most important scientific developments of the 20th century. He almost single-handedly made the origin of species diversity the central question of evolutionary biology that it is today. He also pioneered the currently accepted definition of a biological species: an interbreeding population that cannot breed with other groups.

Throughout his nearly 80-year career, as his research ranged throughout ornithology, taxonomy, zoogeography, evolution, systematics, and the history and philosophy of biology, Mayr maintained an unshakable faith in Darwin’s theory of evolution.

“I’m an old-time fighter for Darwinism,” he told the Harvard Gazette in a 1991 interview. “I say, ‘Please tell me what is wrong with Darwinism. I can’t see anything wrong with Darwinism.’”

Born July 5, 1904, in Kempten, Germany, Mayr earned a medical degree from the University of Greifswald in 1925. Descended from generations of doctors, he broke off his medical career and turned his attention to zoology, earning a Ph.D. from the University of Berlin just 16 months later.

“I was curious about far places,” he told the Harvard Alumni Bulletin in 1961, “and decided that as an M.D., I should have but small chance of traveling.”

His chance to do so came in 1927, at the International Zoological Congress in Budapest, when he met Lord Rothschild, who had been seeking someone to travel to New Guinea to collect birds of paradise. Mayr jumped at the chance, and spent the next two and a half years in the South Seas, seeking out populations of birds that, isolated from fellow members of their species, had accumulated genetic differences.

“I did one thing after another that I had no business of doing, but I was confident I could do it and, by God, I was able to do it,” Mayr told The New York Times in 1997, describing his “appalling self-confidence” as a young scientist.

In his travels in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, Mayr showed what Darwin had never quite succeeded in establishing: that new species arise from isolated populations. He published his findings in the 1942 book “Systematics and the Origin of Species.” Mayr eventually authored or co-authored more than 20 books, including the seminal texts “Animal Species and Evolution” (1963) and “The Growth of Biological Thought” (1982), and contributed to well over 600 papers published in peer-reviewed journals.

Throughout his career, Mayr fought tirelessly to ensure biology’s place in the pantheon of “true sciences,” alongside physics, astronomy, and chemistry – a view not shared by many scientists as late as the 1960s. Driven by a lifelong interest in the “why” of evolutionary biology, he also pioneered the study of the philosophy and history of biology.

“Much as we know about the ‘how’ of human evolution, the ‘why’ is still a great puzzle,” he wrote in 1963, a theme still very much in evidence in his most recent books.

Among his many honors, Mayr captured the three prizes widely regarded as the “triple crown” of biology: the Balzan Prize in 1983, the International Prize for Biology in 1994, and the Crafoord Prize in 1999. In accepting these awards, Mayr donated the hundreds of thousands of dollars in prize money to such organizations as Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology and the Nature Conservancy. “The money is the least important part of the prize,” he told the Harvard Gazette upon winning the Balzan Prize.

Mayr was also awarded the National Medal of Science in 1970.

Mayr’s wife, Margarete, died in 1990 after 55 years of marriage. He is survived by two daughters, Christa Menzel of Simsbury, Conn., and Susanne Harrison of Bedford, Mass.; five grandchildren; and 10 great-grandchildren. Plans for a memorial service on the Harvard campus will be announced at a later date.