History of life on Earth is largely microbial

Harvard Museum of Natural History exhibit takes life back to tiny roots

Earth’s first life appeared early in the planet’s history, nearly 4 billion years ago, when primitive bacteria appeared in sulfurous oceans under poisonous skies.

Full of carbon dioxide and nitrogen, with some additional hydrogen, water vapor, and perhaps a bit of methane, it would be billions of years before the air would be acceptable to today’s oxygen breathers.

And we all have bacteria to thank.

It was bacteria that gave life its initial foothold, and it was bacteria by the trillions that engineered the planet for our use, taking in carbon dioxide and giving off oxygen, day in and day out for billions of years until there was enough oxygen in the atmosphere to support larger life.

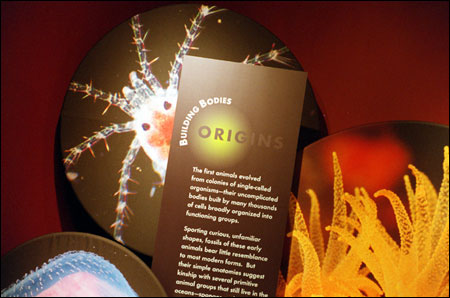

A new exhibit at the Harvard Museum of Natural History (HMNH) is dedicated to this early period of life on Earth. Called “Origins: Life’s First Three Billion Years,” the exhibit opened Oct. 2 and runs through May 1, 2005.

It highlights the work of Fisher Professor of Natural History and Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences Andrew H. Knoll and colleagues, who have worked for years to illuminate the rise of early life and the effect it had on our juvenile planet.

Knoll said the exhibit is designed to dispel common misperceptions about Earth’s history that see life starting with dinosaurs and progressing forward with mammals and, finally, man.

In fact, Knoll said, the history of life on Earth is largely microbial. For vast stretches of time, bacteria and other single-celled organisms were the only life on Earth. The age of the dinosaurs to the present day, Knoll said, represents roughly 5 percent of the history of life.

“When we think about the history of life, we tend to think about dinosaurs or, if you’re really informed, trilobites. That’s just the tip of the iceberg,” Knoll said.

Not only were microbes the first living things on Earth, they were critical to the Earth’s transformation. The rise of photosynthetic bacteria called cyanobacteria was a crucial step because these bacteria ingested carbon dioxide and released oxygen.

They multiplied until eventually they were producing more oxygen than the planet’s natural processes consumed, and oxygen began to build up in the atmosphere.

“Most of the life on the planet is microbial,” Knoll said. “You can certainly run a world without dinosaurs and humans, but you can’t do it without microbes.”

The exhibit itself is a first for the museum, according to the HMNH’s Executive

‘Origins: Life’s First Three Billion Years’ is on exhibit through May 2005 at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, 26 Oxford St. Open daily 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Admission is $7.50 for adults; $6 for seniors citizens and students; $5 for children 3 to 18; free for children under 3. Call (617) 495-2341.

Director of Public Programs Joshua Basseches, because it is the first Harvard Museum of Natural History exhibit designed to travel to other institutions. Though the schedule is still being determined, Basseches said the exhibit’s mobility is an important step in the museum’s goal of presenting the work of Harvard scientists to the public.

Knoll said the exhibit is the first of a series of traveling exhibits the museum hopes to design in the coming years.

“This is the first in a series of exhibits … that will highlight issues of broad scientific interest to which Harvard faculty have made contributions,” said Knoll, who also serves as curator of the paleobotanical collections in the Harvard University Herbaria.

The exhibit follows a chronological track, greeting visitors with a large picture of a glowing river of lava flowing off a cliff into the ocean and setting the stage with a description of the early Earth. The planet was born 4.6 billion years ago, and by 3.8 billion years ago, life had already established a foothold.

But that early life had a lot of work to do.

Various displays take visitors through this early history, coupling photos, printed narrative, and video with samples from the museum’s collections. The exhibit takes a visitor on a walk through various milestones: the first life, the first oxygen in the atmosphere, the first complex cellular life, the first simple animals such as jellyfish, sponges, and corals, and finally, the rise of complex animals.

The final display contains recent pictures of Mars, the center of a current discussion about life’s origins. Knoll said once we understand how life on Earth evolved, we can begin to think about the possibility of it arising on other planets as well.

“The final question is a big one,” Knoll said. “There are a lot of planets out there.”