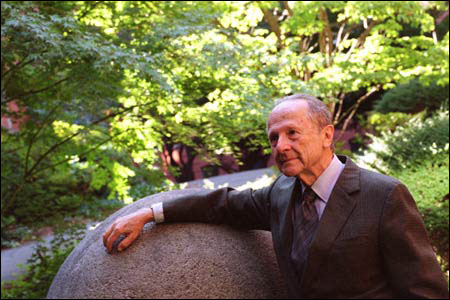

Matthew Meselson wins 2004 Lasker Award

Biologist honored for a lifetime of achievement

Harvard biologist Matthew Meselson has won the 2004 Lasker Award for Special Achievement in Medical Science. The prize honors a lifetime of solving fundamental biological problems and of helping to curtail the spread of biological and chemical weapons.

On Oct. 1 in New York City, the Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of Natural Sciences will receive an honorarium of $25,000 and a statuette of the Winged Victory of Samothrace, a symbol representing victory over disability, disease, and death.

Besides Meselson, four other scientists will receive Laskers. Three will be honored for discoveries in the fields of hormone research and metabolism that have added to our understanding of disease and embryonic development. A fourth will get the award for the invention of noninvasive cataract surgery.

Awarded by the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation, these laurels are often called “American Nobel Prizes.” Since 1946, when they were first given, 68 Lasker awardees have gone on to receive Nobels.

The special achievement award celebrates Meselson’s contributions to our knowledge of how genes replicate, repair themselves, reject foreign DNA, and instruct the body to make the proteins it needs. In addition, notes Joseph L. Goldstein, holder of both a Nobel and a Lasker and chairman of the jury that selects Lasker recipients, “Meselson has been tireless and passionate in leading successful efforts to persuade the United States government to abandon its biological and chemical weapons programs.” He played a key role in the decision of former President Richard Nixon to unilaterally end the nation’s biological weapons program in 1969.

Meselson also helped resolve some intriguing international mysteries. He investigated “yellow rain,” a supposed poison that the Vietnamese government, with the assistance of the Soviet Union, was spraying on antigovernment tribespeople. Meselson and his colleagues found that this “toxic rain” actually consisted of bee droppings. After eating pollen, armies of the insects excreted the waste in massive showers.

In 1979, Soviet authorities reported that 60 people died in Sverdlovsk from eating tainted meat. In the 1990s, Meselson and his wife, medical anthropologist Jeanne Guillemin, visited the site with an investigative team, and showed that the deaths were actually caused by a cloud of anthrax released from a suspected biological weapons facility.

No diploma needed

Meselson got off to a slow start in academia. He finished enough courses at his Los Angeles high school to graduate a year and a half ahead, but school officials would not give him a diploma because he lacked three years of physical education. “That was a shock to me,” he admits. “I didn’t consider physical education to be part of my education; my body would develop no matter what.”

Meselson managed to get into the University of Chicago without a high school diploma, but he ran into another problem. He was interested in uncovering the secrets of life though chemistry, but the university didn’t give degrees in that subject. He had to settle for a letter stating that, if the university did give bachelor’s degrees in chemistry, it would certainly have given him one. Instead, Meselson received a degree in philosophy.

His luck changed when he went to the California Institute of Technology where he met Linus Pauling, who later won two Nobel Prizes, one for chemistry and one for peace. Pauling was in a race with James Watson and Francis Crick to puzzle out the structure of DNA, the stuff of genes. Pauling lost, but Meselson and Franklin Stahl, a postdoctoral student, provided compelling evidence of how that structure duplicates itself.

“Once you see the structure of DNA, it talks to you,” Meselson comments. “It tells you how it duplicates itself, how it makes offspring different from parents, how it can correct its own mistakes, and how the information it contains can make living things the way they are. It’s a guidebook to the secret garden of life.”

In succeeding years, the scientific community hailed Meselson for the experiments he conducted to dig up the secrets in this garden.

Disarming experiences

Meselson moved from Caltech to Harvard in 1960. Because of his interest in controlling weapons of mass destruction, he was invited to work at the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency in Washington during the summer of 1963. When he learned about the large program the United States had in biological weapons, he asked why those weapons were being made. “I was told that they were cheaper than nuclear weapons,” he recalls. “It seemed to me a terrible answer, that it would not be in our interest to pioneer weapons of mass destruction that are so cheap many others also could have them.”

Meselson knew Henry Kissinger, who worked at Harvard before he became President Nixon’s national security adviser. They cooperated to help convince Nixon to renounce biological weapons unconditionally, suspend production of chemical weapons, and support an international treaty prohibiting the development, production, and acquisition of biological agents for hostile purposes. This 1972 treaty became known as the Biological Weapons Convention.

Despite their agreement on this important issue, Meselson wound up on one of Nixon’s infamous “enemy” lists, along with Derek Bok, then president of Harvard. “I called Derek and told him about it,” Meselson remembers. “It didn’t seem to bother him much. There was no downside for me, I continued to consult at the White House.”

Currently, Meselson, along with Julian Perry Robinson of the University of Sussex in England, co-direct an effort to establish an international treaty that prohibits biological and chemical weapons. Called the Harvard-Sussex Draft Convention, it would give the courts of participating nations jurisdiction to treat providers of these weapons as international criminals, like existing treaties that govern airline hijacking, torture, and hostage taking.

Although there is not much interest in the United States, several European nations favor such an agreement. “We plan to have a high-level conference on it next year in The Hague,” Meselson reports.

Researching sex

With all this going on, Meselson has not slighted teaching or research. His ex-students include Nobel Prize and Lasker Award winners.

At present, he and his students are probing why sex is necessary for evolution. Some small aquatic animals, bdelloid rotifers, have survived for millions of years without it. There well may be other creatures, yet unknown, that also have reproduced asexually for eons.

Sexual reproduction, wherein offspring get half their genes from one parent and half from the other, offers more advantages in evolution. Why this is so remains unknown. Meselson and his colleagues theorize that the advantage of sex may lie in its ability to reduce what he calls “genetic parasites.” These are pieces of DNA that multiply on their own and can cause genetic damage. Bdelloid rotifers don’t appear to have such parasites.

Getting better answers to why sex exists could turn evolution on its Darwinian head, or not. If Meselson doesn’t change biological knowledge in a big way with this research, perhaps one of his students will – and win a Nobel, a Lasker, or both in the process.