Late bloomer

Architectural history scholar now fine artist

As the author of several highly respected works of architectural history, William J.R. Curtis receives many new volumes for review, a good portion of them large-format books filled with photographs and reproductions. While he is not always impressed with these tomes as works of scholarship, he does appreciate the packaging they come in, the corrugated containers, the sheets of mottled industrial cardboard, the plain brown wrappers.

These materials often end up incorporated into Curtis’ artwork, a generous selection of which can now be seen at the Carpenter Center under the title “Mental Landscapes: Drawings and Paintings by William J.R. Curtis.”

While Curtis has always kept a sketchbook handy to record his impressions of the buildings and landscapes he encounters on his travels, the abstract works that make up the current exhibition are of more recent vintage.

“About seven or eight years ago, it all crystallized, and I suddenly had the feeling of having a language. After that, I produced quite a lot of work in a relatively short time,” he said.

The scale is intimate, from the size of a legal pad down to that of a postcard, so that for a long time he was able to carry his complete oeuvre with him wherever he went. He found that the reactions of the art historians and architects to whom he showed the pieces were generally positive and encouraging.

A Finnish colleague helped Curtis make the transition from private to public artist when he looked the works over and made the laconic pronouncement: “Serious business, William.”

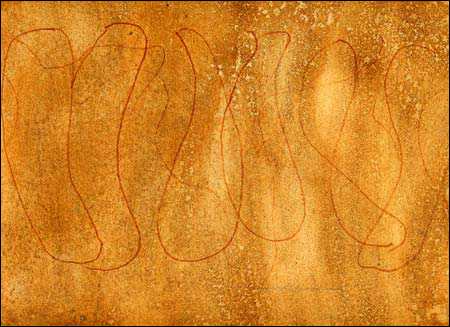

The pieces themselves are small, modest, quiet, uninsistent. A few might be mistaken for half-conscious doodling, others for sections of wrapping paper designed for some particularly somber holiday, others for samples of faux sandstone or cherry veneer. But it is their very modesty that forces the viewer to come in close and contemplate the calligraphic pen strokes, the overlapping layers of ink wash, the mysterious slashes and indentations that show faintly through coatings of dark paint.

“They seem very quiet, but the process of creating them is a very intense one. Some of them were done in a kind of trance state. Behind them there is a vibration of many places and many myths,” Curtis says.

Those places include the coast of Kent in England where Curtis grew up contemplating the vast, changeable face of the North Sea, as well as northwest France, where he now lives, with its dramatic limestone cliffs and gorges ó and the recently discovered Grotte Chavet containing 30,000-year-old cave paintings. These landscapes inform Curtis’ artwork, but in a particular way.

“They’re abstractions but rooted in an experience of nature.”

The works are not attempts to copy nature, he emphasizes, nor to give form to a particular aesthetic concept. Rather, they are a distillation of experience intended to provide a focus for contemplation, a doorway into another reality, something like the Zen gardens of Kyoto, which are another influence on Curtis’ work.

“Every work has to be a discovery, something that has never existed before, something living. At the same time I want them to embody traditional concepts of harmony and tranquility.”

The show at the Carpenter Center is only the third or fourth time Curtis has exhibited his work, but this show has a particular significance for him. He earned his Ph.D. in art history from Harvard in 1975 with a dissertation on the Carpenter Center, one of the last buildings designed by the great modernist architect Le Corbusier. He also taught in the building until 1982, giving courses on basic concepts of visual experience.

Curtis’ dissertation adviser was Eduard Sekler, the Osgood Hooker Professor of Visual Arts Emeritus, who contributes a short essay to the brochure that accompanies the show. In it, he describes Curtis as a well-trained and talented scholar, but one in whom he sensed “creative impulses” that might someday lead him beyond the boundaries of his profession.

“It came as no great surprise, therefore, when some years ago he showed me for the first time drawings of the kind now exhibited here,” Sekler wrote.

“It’s quite an emotional thing for me to come back and do this here,” says Curtis. “My period here was a very formative one. I saw the Carpenter Center for the first time on Sept. 9, 1970, in the pouring rain, and I never would have guessed how central in my life it would become. This is a very special and touching moment for me.”

The exhibition will remain on view through Aug. 15.