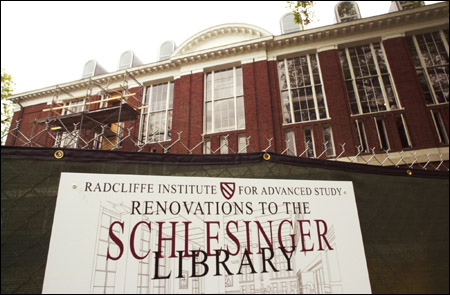

Schlesinger Library recycles while it renovates

Trendsetting effort recycles 80 percent of demolition waste

The Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study is a monument to preservation. The library’s extensive collections of books and manuscripts, from Julia Child’s recipe files to Amelia Earhart’s baby book to oral histories of black women, preserve and perpetuate an understanding of women’s lives for future generations of scholars.

Now, as it undergoes a major renovation, the Schlesinger is taking a global view of preservation by mounting a recycling effort that will divert a significant portion of demolition and construction waste away from landfills. As the demolition concluded last month, more than 80 percent of the waste that was generated, or 118 out of a total 141 tons, was reused or recycled. Project manager Kate Loosian of Harvard Real Estate Services estimates that by the project’s conclusion, on schedule for winter 2005, an estimated 50 to 60 percent of total waste will be recycled.

“It’s been surprisingly easy,” says Loosian. “It’s not all that different [from ordinary construction disposal], and it’s certainly the right thing to do.”

While the Schlesinger project may not be the first large-scale recycling effort to accompany construction at Harvard, Loosian says it’s noteworthy in the significant commitment it signals for Radcliffe as a relatively small “tub.” A dedication to doing the right thing runs deep at the library, says Megan Sniffin-Marinoff, deputy director of the Schlesinger; in the past, staff even went so far as to compost coffee grounds and paper towels from the kitchen. “This library has always tried to be socially responsible in everything it does, from what we collect to making our library collections freely accessible to all,” says Sniffin-Marinoff. “In a way, this is an extension of the spirit of the library.”

This passion for recycling and living lightly on its piece of the Earth goes beyond the Schlesinger to the entire Radcliffe Institute. “It’s just something that’s part of the culture here,” says Louise Richardson, Radcliffe Institute executive dean. “We’re very conscious of the fact that we have this beautiful space, and recycling strikes us as a way of respecting that space.”

The Schlesinger renovation, estimated to cost between $6 million and $7 million, will install new climate control equipment and reconfigure the library’s space to make a more functional venue for researchers from Harvard and around the world.

Sinks to Roxbury, shelves to New York

Before recycling on this scale can benefit the planet, an entire village of intertwined services must work together to ensure that everything from old chairs to gypsum wallboard finds life outside landfills. Many past projects generally sent dated or unused furniture out to the dumpster, says Loosian. Instead, she went to Rob Gogan, supervisor of waste management and Harvard’s most enthusiastic recycling resource, who connected the project with the New Hampshire-based consultants the Institution Recycling Network (IRN).

Before the project began, IRN worked with Schlesinger general contractor Richard White Sons and various subcontractors to plan for separating and recovering waste. Loosian credits this up-front work with what she describes as a “shockingly” smooth process. “I very much went into this expecting that [the contractors] would come back and say ‘it’s taking us more time, we don’t have the space on the site, it’s more expensive,’ and I have not seen that,” she says, adding that Richard White Sons have “really gotten on board with the effort and embraced it as well.”

But as any home recycler knows, good recycling only begins with separating waste – it has to go somewhere. The Schlesinger project tapped Gogan’s extensive network of nonprofits to donate study carrels, bookshelves, office partitions, and other furnishings to organizations in need; so far, 70 percent of those furnishings have found new homes at institutions such as the King Elementary School in Cambridge, the Boston Police Department and Boston Housing Authority, and a public library in New York. More than 2 tons of furnishings and other moveable assets remained at Radcliffe, where they were redistributed to other offices.

Reusable building components like cabinetry, bathroom fixtures, and doors went to the Boston Building Materials Resource Center, a nonprofit organization that provides lower-income homeowners with materials to repair and renovate homes.

As the project moves from demolition to construction, the recycling rate will dip somewhat, but contractors will continue to separate and recycle metals, wood, and other materials that would otherwise end up as trash.

Honoring a legacy

Although recycling slashes disposal costs, both Loosian and Sniffin-Marinoff anticipate that the recycling of the Schlesinger will come at a modest cost to Radcliffe. “But if you take a long-term perspective, it’s certainly worth it,” says Richardson.

Beyond basking in the warm green glow of recycling, Radcliffe will serve as a trendsetter and role model to other construction and renovation projects around the University. Loosian notes that more Harvard construction projects – the new rare book library and document restoration center at 90 Mt. Auburn St. is a current example – are recycling construction and demolition waste and seeking certification by the United States Green Building Council via its Leadership for Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standard.

And construction recycling likely won’t be optional for much longer, says Loosian. As early as the end of 2004, Massachusetts may begin to enforce legislation that says that construction and demolition waste can’t be sent to regular landfills. “Because it will soon be a mandate, it’s great to have had such a positive experience in advance,” she says.

At Radcliffe, the push to recycle has a personal side, too. “I see [this project] as part of the legacy Scott Sandberg left us,” says Richardson of the beloved Radcliffe employee who died in an avalanche on New Hampshire’s Mt. Washington in November 2002. As building services coordinator and “recycling king” at Radcliffe for four years, Sandberg brought the institute’s recycling rate from 25 to 72 percent and was honored by the city of Cambridge for his efforts. “Scott was such a huge presence around here. I see this very much as honoring his memory,” Richardson says.